Introduction

The frequent development of viral and bacterial infections in the aquaculture process jeopardizes the crab farming industry’s long-term survival.1,2 At present, aquaculture farmers predominantly utilize antibiotics for disease prevention and treatment in their operations.3 Although antibiotics can reduce the incidence of diseases to a certain extent, their excessive use has been associated with a rise in bacterial resistance.4 Given the deleterious consequences of antibiotic misuse, there has been a shift in focus towards the utilization of probiotics as a potential substitute for antibiotics in mitigating these negative effects. Recently, the employment of probiotics in aquaculture has garnered recognition for its multifaceted benefits, which include enhancing growth performance, curbing disease incidence, bolstering immune responses, and contributing to host digestion through nutritional support.5

Probiotics are essential for preserving the equilibrium of the gut microbiome, boosting immune function, and protecting against various diseases.6 Common types of probiotics include bacillus, lactic acid bacteria, bifidobacteria, and yeasts. These beneficial microbes are found in foods, supplements, and the gut microbiota of humans and animals.7,8 In aquaculture, the application of probiotics has gained significant attention. These beneficial microorganisms can be introduced either as feed additives or directly into the aquatic environment, where they improve water quality, inhabit the reproduction of harmful bacteria, and foster the overall health and growth of aquatic species.9 For instance, lactic acid bacteria, bacillus species, and yeasts are widely used in the farming of shrimp, fish, and shellfish. Prior studies have shown that the application of probiotics in crab culture can significantly enhance growth, stimulate the immune system, and exert control over diseases.10 Probiotics have been shown to augment microbial diversity in the aquaculture ecosystem, thereby strengthening the disease resistance of aquatic species, diminishing the reliance on antibiotics, and mitigating environmental pollution.11

C. butyricum is a Gram-positive, anaerobic bacterium capable of forming endospores and is widely recognized for its probiotic properties, particularly its capacity to generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), with butyric acid being the most notable. This microorganism is instrumental in promoting the reconstitution and renewal of intestinal epithelial cells, as well as in maintaining a balanced intestinal microecological environment.12 Research has indicated that butyric acid is capable of elevating growth rates and enhancing disease resistance in organisms.13 Within the domain of aquaculture, C. butyricum has gained significant attention as a key probiotic, effectively ameliorating growth performance, augmenting feed conversion efficiency, elevating antioxidant defenses, and modulating the immune system in aquatic species. For instance, the admixture of 1.5 × 109 CFU/kg of C. butyricum in food of largemouth bass resulted in notable improvements in growth, antioxidant capacity, and resilience to hypoxic stress.14 Similarly, research demonstrated that supplementing the diet of Penaeus vannamei with 1011 and 1012 CFU/kg of C. butyricum led to significant improvements in growth performance and immunocompetence.15 Additionally, Bi reported that incorporating 107 CFU/g of C. butyricum H129 into the diet of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) positive influence.16 In vitro fermentation experiments carried out with the intestinal contents of mud crabs indicated that C. butyricum G13 notably enhanced the generation of butyric acid and had a positive impact on the abundance and diversity of the gut microbiota.17

The mud crab, Scylla paramamosain, holds substantial economic value in the aquaculture industry.18 However, in the current aquaculture process, the disease problem has always been a serious challenge. Among them, Vibrio infection is one of the common diseases in mud crab breeding. After infection with Vibrio, the mud crab was slow or even stagnant, the food intake decreased significantly, and eventually died of exhaustion due to physical deterioration. And the effects of different concentrations of commercial C. butyricum on the health of S. paramamosain have not been reported. This study aims to fill that void by examining how different concentrations of C. butyricum influence key aspects of mud crab biology, including growth rates, immune response, gut microbiota balance, and resilience against Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections. The insights gained from this research will provide crucial direction for employing C. butyricum to optimize mud crab farming, thereby laying the foundation for more enduring and effective aquaculture practices.

Materials and Methods

Experimental strains and diets

The Clostridium butyricum isolate employed in this research was sourced from Guangzhou Xinhailisheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China. The minimum bacterial concentration recorded was 8×108CFU/ml. The commercial feed sourced from Zhuhai Puleduo Aquatic Feed Co., Ltd. was used as the basic diet (Table 1). In the process of formulating the experimental diets, the concentration of the original bacterial solution was determined by the plate coating method, and it was diluted according to the required concentration and sprayed on the basic feed. Stir with a spoon to ensure that the bacterial solution is evenly distributed on the feed surface and then dried. The control group (CC) was fed the unaltered base diet. In contrast, the experimental groups received the base diet supplemented with C. butyricum at concentrations of 3.6 × 104CFU/g(CB1), 3.6 × 105 CFU/g(CB2), 3.6 × 106 CFU/g(CB3), and 3.6 × 107 CFU/g(CB4) respectively.

Experimental Animal

From a crab breeding site in Taishan, Guangdong Province, China, healthy mud crabs weighing 16 ± 1g were acquired. The crabs were kept in tanks with a temperature of 22 ± 1°C, a salinity of 8‰, and a dissolved oxygen content of 9.0 ± 0.5 mg/L for a week before the experiment started. Following a brief period of feeding, 255 healthy mud crabs were split into five groups at random and kept in an aquarium of 50 × 30 × 40 cm with identical circumstances. The feed was fed once in the morning and once in the evening, 3% of the body weight was fed each time, and the feed was continuously fed for 42 days. In order to ensure that the water quality was always maintained at a high level, it was replaced every three days.

Sample collection

After completing the feeding trial, the mud crabs were kept fasting for 24 hours. The crabs were then weighed, and the number in each tank was totaled. From each group, twelve crabs were chosen at random. Hemolymph was drawn using syringes that had been pre-treated with anticoagulant. Following centrifugation at 4℃ and 8000g for 15 minutes, the serum was obtained and promptly kept at -80℃ for subsequent enzyme activity testing. After blood sampling, the exterior of each crab was gently cleaned with a cotton ball soaked in 75% alcohol. The crab was then dissected and its intestine was extracted. A portion of the intestine was immersed in RNAlater solution to assess intestinal gene expression levels. In order to analyze the intestinal microbiota and enzyme activity later, the remaining piece was quickly refrigerated at -80°C. The hepatopancreas was aseptically excised and kept at -80℃ for enzyme activity testing.

Growth performance

Calculations were utilized to determine the weight gain rate (WGR), specific growth rate (SGR), and survival rate (SR):

WGR (%) = [100×(final body weight-initial body weight)/initial body weight]

SGR (%/day) = 100 × [Ln (final individual weight)-Ln (initial individual weight)] /number of days

SR (%) = 100 × (finial number of crab)/ (initial number of crab)

Biochemical indices analysis

Weigh 0.1 g of intestine and hepatopancreas tissues, add physiological saline at a proportion of 1:9, and homogenize. Lipase (LPS), α-amylase (α-AMS) in the intestine, alkaline phosphatase (AKP), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) in the hepatopancreas, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in the serum were detected by kit (Nanjing, China).

Gene Expression Analysis

The extraction of RNA from the intestines of mud crabs was conducted utilizing RNAiso Plus (Takara, Japan) in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. The RNA samples were subsequently subjected to 1.0% agarose electrophoresis analysis and their concentrations were measured at 260 and 280 nm using the Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Single-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara, Dalian, China), following the detailed instructions provided by the manufacturer.

QRT-PCR was utilized to determine gene expression levels in the colon, including IL8, TNF-α, GPx3, PO, P53, and GST. SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara) was used for Real-Time PCR using the qTOWER Real-Time PCR Thermal Cycler (Analytik Jena, Germany). The experiment was repeated three times. The gene expression level was calculated by the 2-△△Ct method with the 18S rRNA gene as an internal reference. The primer sequences were shown in Table 2.

Determination of Intestinal Flora of S. paramamosain

Genomic DNA was isolated from the intestinal microbial community and verified via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The amplification of the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was carried out with the 338F and 806R proprietary amplification system methods. The PCR outcomes from the identical sample were pooled and analyzed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. After that, they were retrieved with the employment of the AxyPrep DNA gel recovery kit (AXYGEN business) and eluted with Tris-HCl solution before being electrophoresed again on 2% agarose gels. According to the preliminary quantitative findings obtained by gel electrophoresis, the products of PCR were further measured using the QuantiFluorTM-ST blue fluorescence quantitative system (Promega). The outcomes were then combined in the correct amounts to meet the sequencing requirements of each sample. Meiji Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., based in Shanghai, China, sequenced the amplified products using the Illumina HiSeq platform.

Challenge test

Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains were sourced from the Disease Laboratory of South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences. The experimental group was fed with a diet rich in 3.6 × 106 CFU/g C. butyricum, and the control group was fed with normal diet for 30 days. Following the food intake test, 50 crabs were randomly chosen from experimental groups and the control group, respectively, and divided into 5 replicates, 10 crabs in each replicate, for challenge test. The concentration of V. parahaemolyticus was ascertained to be 1×107 CFU/ml by the spread plate technique. Each crab was injected with 0.1 ml of live Vibrio parahaemolyticus at the base of its swimming leg. The hemolymph was collected at 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, and 144 hours after challenge. These samples were diluted and cultured on nutrient agar plates at 28℃ for 12 hours, after which the colony counts were determined. Concurrently, the survival rate of the crabs was monitored and documented at 12hour intervals, and a survival curve was constructed based on these data.

Analysis of Data

All the experimental data were presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was conducted utilizing SPSS 26.0. The significance of differences among the control and treatment groups was assessed via ANOVA. Survival analysis outcomes were visualized using GraphPad Prism software. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Growth performance

When C. butyricum was incorporated into the feed, S. paramamosain gained more weight and had faster specific growth rates than the control group. They initially grew, then reduced as the concentration of C. butyricum increased. Notably, the CB2 and CB3 groups outperformed the other groups in terms of weight increase and specific growth rates. (P<0.05, Table 3).

Effect of C. butyricum on enzyme activity of the S. paramamosain

Figure 1 depicts the impact of introducing C. butyricum into the meal on crab non-specific immunological measures. Following C. butyricum treatment, lipase (LPS) activity in S. paramamosain’s gut was higher compared to the control group, initially rising and then declining as C. butyricum concentration increased. The LPS activity in CB2 and CB3 groups was considerably greater than in the other groups. (P < 0.05; Figure 1G). As for the amylase (AMS) activity in the gut, it also elevated after feeding C. butyricum, with the CB3 group exhibiting the highest activity. However, differences across the groups were not statistically noteworthy (Figure 1H).

In S. paramamosain, the level of activity of antioxidant-producing enzymes dramatically increased following dietary intake of C. butyricum (P < 0.05). As the concentration of C. butyricum increased, the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) initially increased and then decreased. Notably, compared to the other groups, the CB3 group’s activity levels were noticeably higher (P < 0.05; Figure 1A, B).

Incorporating C. butyricum into the diet led to a rise in alkaline phosphatase (AKP) activity within the hepatopancreas of S. paramamosain with the increase of the concentration. The AKP activity in the CB3 and CB4 groups was notably elevated than that of the other groups (P<0.05). Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels fell initially and then increased as C. butyricum concentration increased. Specifically, the CB3 group showed markedly lower ALT activity than the control group, whereas the CB4 group had significantly elevated AST activity relative to the others (P< 0.05; Figure 1C, D and F).

Expression Levels of Intestine Immune Related Genes

After 42 days handled with C. butyricum in the diet, alterations in the expression of intestinal immune genes in mud crabs were observed. The expression levels of IL8, TNF-α, GPx3, GST, P53 and SpPO genes in the intestinal of crabs across various treatment groups were illustrated in Figure 2. The expression levels of IL8 and TNF-α rose in tandem with the increasing concentration of C. butyricum. Notably, compared to the control group, the expression levels in the CB3 and CB4 groups were much elevated (P<0.05). The expression levels of GPx3 and SpPO genes increased first and then declined as the quantity of C. butyricum increased, and the expression levels in the CB3 group were considerably greater than those in the control group (P<0.05). The expression of GST in the intestine of crabs after adding C. butyricum was notably less than that of the control group except for CB3 group (P <0.05). The addition of C. butyricum exerted little influence on the expression of P53 gene in the intestine of mud crab.

Microbiota community characterization in the intestine

A comprehensive analysis of the gut microbiota from 15 samples yielded a total of 1,740,226 sequences, averaging 116,015 sequences per sample. The microbial diversity was extensive, encompassing 12 phyla, 18 classes, 45 orders, 68 families, 116 genera, and 138 species of gut microorganisms. The Chao1 and ACE indices increased initially before decreasing as the concentration of C. butyricum in the feed went up, with the CB3 group showing the highest values. The CB3 group had a higher Shannon index than the other groups but a lower Simpson index (Table 4).

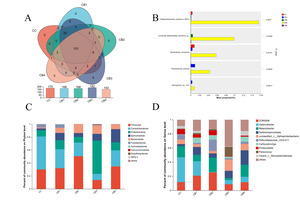

Based on the Venn of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU), the number of OTU shared by the experimental and control groups was 123. As the dietary concentration of C. butyricum increased, the OTU count in each group initially rose and then declined, with the CB3 group exhibiting the highest OTU number (Figure 3A). Firmicutes, Campilobacterota, Proteobacteria, Spirochaetota, and Bacteroidota were the dominant phyla across all groups. Campilobacterota were all decreased to different degrees in the experimental groups, with the lowest levels in the CB3 group (Figure 3C). Proteobacteria had the highest content in the CB3 group. The widespread genera in each group were ZOR0006, Halarcobacter, Malaciobacter, Sediminispirochaeta, and Alphaproteobacteria (Figure 3D). The CB3 group had considerably increased levels of Deltaproteobacteria, Marinifilaceae, Hanstruepera, Pseudomonas and Sphingobium compared to the control and other experimental groups (Figure 3B).

Analyzing the varied abundances of the five groups of bacterial species using linear discriminant analysis. In the control group, the Chloroflexi and Anaerolineae had the highest Effect Size (LEfSe) among the differential bacteria with LDA values larger than 2.0. In the CB3 group, there were substantial variations in 1 class, 3 orders, 4 families, and 7 genera. In contrast, there were no significantly different species in groups CB1, CB2 and CB4 (Fig. 4A, B). Functional analysis using KEGG Pathway Level 2 revealed that the experimental group had a greater abundance of metabolic pathways than the control group, with the CB3 group showing the most elevated levels (Figure 4C).

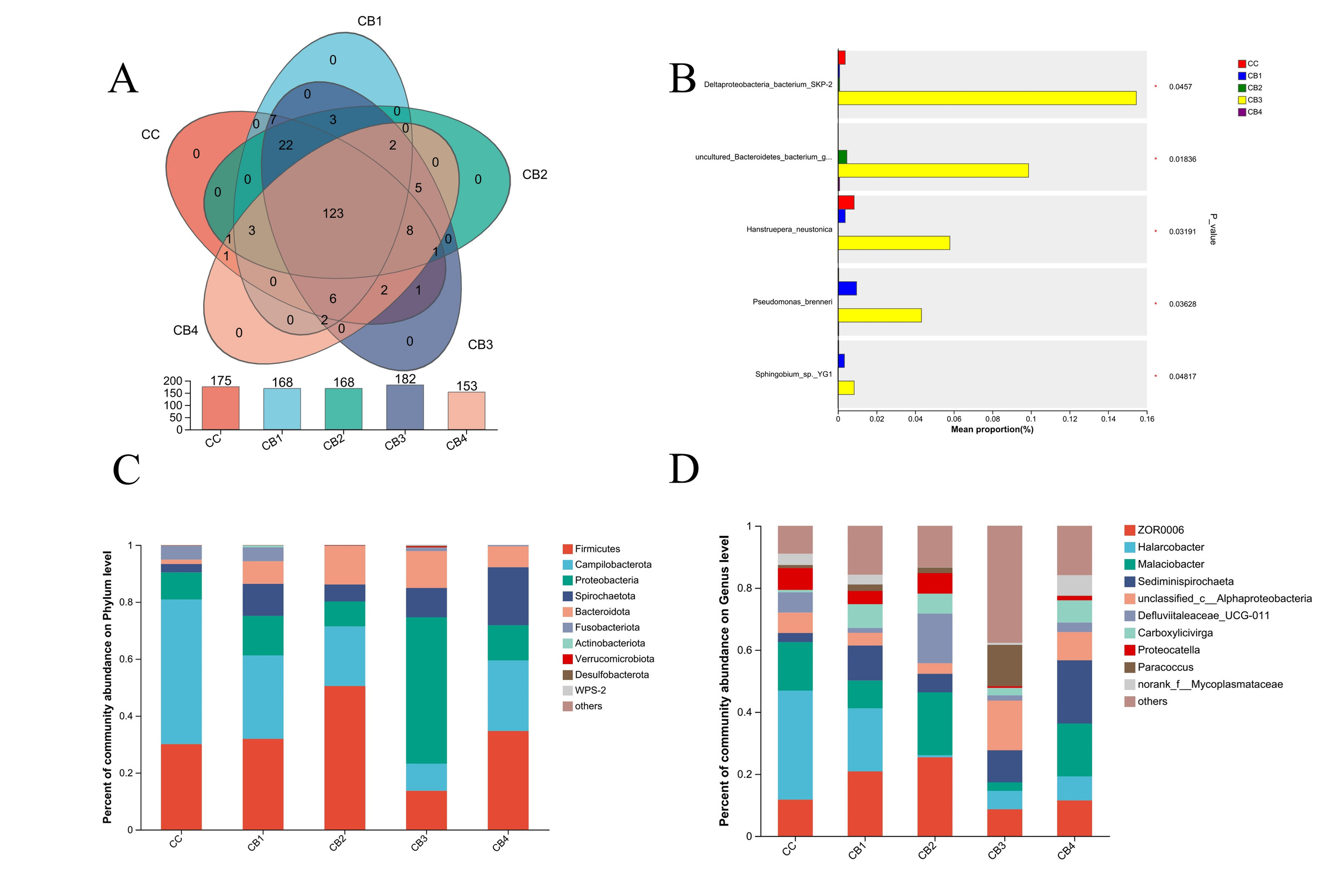

Challenge test

The addition of C. butyricum in the feed affected the resistance of S. paramamosain to V. parahaemolyticus infection. As shown in (Figure 5A), the survival rate of crabs in CB3 group was significantly higher than that in CC group. In (Figure 5B), V. parahaemolyticus began to grow in the hemolymph of the control group at 12 hours after challenge, reaching 105CFU/ml at 144 hours, while V. parahaemolyticus was detected in the CB3 group at 48 hours, reaching 104CFU/ml at 144 hours, which was significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The utilization of probiotics in the realm of aquaculture has emerged as an important and growing field of study and practice. With the increasingly rigorous regulations on the use of antibiotics, probiotics have attracted more attention and investigation as a viable and effective alternative.19 Probiotics can improve the growth of aquatic animals by increasing the synthesis of intestinal vitamins and cofactors and promoting the activity of digestive enzymes.20 C. butyricum is a gram-positive anaerobic bacterium that produces butyric acid and has key probiotic roles in the gut. C. butyricum has recently received increased interest in aquaculture due to its broad usage in improving intestinal health, immunity, and growth performance in aquatic creatures. Research has consistently established that C. butyricum can produce short-chain fatty acids, enhance intestinal barrier function, inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria, and enhance individual antioxidant capacity and hunger immunity.5 Studies have shown that the addition of C. butyricum to the feed can significantly increase the weight gain rate of tilapia and reduce the feed-to-weight ratio.20 In this experiment, compared with the control group, the addition of different concentrations of C. butyricum in the feed increased the weight gain rate and specific growth rate of S. paramamosain. The addition of 3.6 × 105 CFU/g and 3.6 × 106 CFU/g significantly increased the weight gain rate and specific growth rate of mud crab (P <0.05).

Digestion is essential to an animal’s metabolism since it provides energy for all biological functions. Biochemical examination of digestive enzyme activity serves as a straightforward and dependable approach to assess the digestion level in individual organisms.21 Prior studies have indicated that Scophthalmus maximus fed with C. butyricum H129 (107CFU/g) significantly increased the amylase enzyme activity.16 However, the optimal addition of different organisms is different. This study found that supplementing mud crabs with 3.6 × 106 CFU/g C. butyricum dramatically improved their intestinal α-amylase and lipase activities. Therefore, C. butyricum can enhance the digestive ability of mud crabs, which in turn promotes growth.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) describe a group of different molecular oxygen derivatives produced during normal aerobic metabolism. A variety of ROS production and scavenging systems actively maintain intracellular redox status, mediate redox signals, and regulate cell function.22 However, high concentrations of ROS induce oxidative stress, which disrupts the normal physiology of the organism and may lead to fatal diseases.23 In contrast, antioxidants can have a prophylactic scavenging role by eliminating excess free radicals, thereby reducing oxidative stress.24 It has been demonstrated that dietary probiotics can augment innate immune responses by modulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) production during pathogen invasion, which in turn stimulates the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD).25 Butyric acid is capable of regulating oxidative stress through the reduction of reactive oxygen species and the enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activity.26 SOD, CAT and T-AOC are key components of the antioxidant system. They are of vital significance in antioxidant reactions, contributing to the prevention or repair of oxidative damage. These parameters are commonly utilized as indicators to assess antioxidant capacity in various studies.27A study found that CAT, SOD and T-AOC activities in largemouth bass were significantly higher in the group that added 109 CFU/kg of C.butyricum to food.14 Consistent with earlier studies, dietary C. butyricum supplementation elevated the hepatopancreatic T-AOC and SOD activities in mud crabs, with the most notable increases seen in the CB3 group. The findings imply that C. butyricum can bolster mud crab antioxidant defenses, thereby mitigating the detrimental effects of reactive oxygen species.

The immune system in crustaceans is crucial for defense against pathogens, and its functionality is influenced by nutritional intake and feed composition. Biochemical examination of important hepatopancreatic enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (AKP), and acid phosphatase (ACP) is a good way for assessing immunological function in animals. In research regarding intestinal nutriention metabolism, AKP has been recognized as one of the crucial indicators for evaluating intestinal health. In a healthy organism, high AKP activity promotes food absorption.28 In this investigation, AKP activity in the hepatopancreas of crabs in the CB3 and CB4 groups rose dramatically (P < 0.05). Adding C. butyricum to the meal can considerably lower ALT activity in crab serum, particularly in the CB3 group (P < 0.05). In the experimental group, the AST activity in the CB3 group was the lowest. This shows that the inclusion of C.butyricum can boost mud crab immunological function.

The immune system’s inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms are vital in modulating cellular reactions to pathogens and oxidative stress. Interleukin-8 (IL8) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) are central genes within the inflammatory response pathway. Glutathione peroxidase 3 (GPx3) and glutathione S-transferase (GST) are emblematic genes within the antioxidant pathway. Probiotics have an essential part in strengthening the host’s immune system. Several investigations have found that C. butyricum can boost immunological responses in aquatic species. The addition of C. butyricum to the feed upregulated the relative expression of immune genes proPO, LGBP, Lys, SOD. in the intestine of Penaeus vannamei.29 In this experiment, the addition of 3.6 × 106 CFU/g C. butyricum group significantly upregulated the expression of IL8, TNF-α, GPx3 and SpPO genes in mud crabs, and enhanced their immune response and antioxidant capacity. Meanwhile, the expression changes of GST and P53 genes in CB3 group were not significant in this experiment, suggesting that the regulatory effect of C. butyricum on these genes may be small or limited by the experimental conditions. Overall, C. butyricum has significant potential to improve the immunity and antioxidant capacity of mud crabs, which is worthy of further popularization and application in aquaculture practice.

The makeup of the gut microbiota has an impact on the health of the host and depends on the diet. A variety of factors, such as direct feeding or the intake of feed additives, can lead to changes in the composition of the gut microbiota.28 Consequently, researching the impact of dietary supplements on gut flora holds great significance. High-throughput sequencing technology was used in the current investigation to study the intestinal bacteria of mud crabs fed C. butyricum. The Alpha diversity data indicated that as the concentration of C. butyricum in the meal grew, the richness and variety of microbial communities in the colon increased and then dropped, but not significantly. In vitro fermentation of mud crab intestinal contents with C.butyricum G13 showed that the main phylum in its intestine was Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Baceroidota and Fusobacteriota.17 In this experiment, the primary taxa in the experimental and control groups were Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Campilobacterota. This finding corroborates prior research, highlighting that Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Campilobacterota are the primary phyla in the mud crabs.

Studies have shown that the main bacteria in the large-particle biofloc are Planctomycetes, Bacteroidetes, and Alphaproteobacteria, which can be used as natural probiotics to limit the growth of pathogenic microorganisms and bolster the immunity and survival rate of animal.23 In this experiment, the CB3 group had a richer genus abundance of Alphaproteobacteria and Paracoccus than the other groups. Furthermore, through the significant analysis of the differences in the species level of different groups, the Deltaproteobacteria bacterium SKP-2, Marinifilaceae, Hanstruepera neustonica, Pseudomonas brenneri and Sphingobium sp. YG1 abundance were considerably greater in the CB3 group compared to the control and other experimental groups. These species encompass a wide range of bacteria with diverse metabolic profiles. As a result of this experiment, it is possible to conclude that C. butyricum has a synergistic effect on the intestinal microbial ecology and health status of S. paramamosain. Functional analysis using KEGG Pathway Level2 showed that adding C. butyricum to the feed increased the abundance of metabolic pathways in S. paramamosain, and the concentration of C. butyricum added to 3.6×106 CFU/g was the most significant (P < 0.05). This may mean that C. butyricum regulates the gut microbiota and promotes individual metabolism.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD2401703), Science and Engineering Guangdong Provincial Laboratory (Zhuhai) (SML2023SP236), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, CAFS (NO.2024RC10), the earmarked fund for CARS-48-21.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Gui-Ying Li (Equal), Zhi-Xun Guo (Equal). Methodology: Gui-Ying Li (Lead), Hong-Ling Ma (Equal), Chang-Hong Cheng (Equal), Guang-Xin Liu (Equal), Zhi-Xun Guo (Lead). Formal Analysis: Gui-Ying Li (Equal), Guang-Xin Liu (Equal). Writing – original draft: Gui-Ying Li (Lead). Writing – review & editing: Gui-Ying Li (Equal), Zhi-Xun Guo (Equal). Funding acquisition: Si-Gang Fan (Equal), Zhi-Xun Guo (Lead). Resources: Jian-Jun Jiang (Supporting), Zhi-Xun Guo (Lead). Supervision: Zhi-Xun Guo (Lead).

Competing Interest – COPE

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical Conduct Approval – IACUC

The crab used in this experiment is a non-regulated invertebrate, which conforms to the ethical standards of experimental animals.

Informed Consent Statement

All authors and institutions have confirmed this manuscript for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All are available upon reasonable request.