Introduction

Utilizing a Regional Innovation System (RIS) theory perspective, this paper constructs and applies an integrated ‘Dynamics-Governance-Space’ (D-G-S) framework to successfully extend RIS theory to Fishing Port Economic Zones (FPEZs)—a typical resource-dependent region—and systematically review FPEZ development research in China over the past decade. The theory of the Regional Innovation System (RIS) describes a complex network of interactions among research institutions, enterprises, government bodies, and other organizations within a relatively small geographical unit.1 This network, formed through cooperation and other formal or informal contacts, facilitates knowledge creation, technology diffusion, and economic growth, thereby fostering the continuous development of its economic agents. As a “resource-dependent” Regional Innovation System, the Fishing Port Economic Zone (FPEZ) is manifested through four key dimensions: knowledge flow, actor networks, institutional embeddedness, and spatial characteristics. Community-level knowledge exchange is crucial for the sustainability of small-scale fisheries.2 The construction of effective information-sharing networks facilitates the flow of knowledge among fishers, researchers, and managers, thereby enhancing managerial adaptive capacity.3 The FPEZ comprises a complex network of diverse actors, including fishers, port managers, enterprises, government agencies, researchers, and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs).4 These actor networks play a vital role in knowledge exchange and resource acquisition; for instance, information-sharing networks can bolster the adaptive capacity of small-scale fishers in the face of change.5 Institutional embeddedness underscores that fishery activities do not exist in isolation but are deeply embedded within specific social, cultural, and political frameworks, which enables community organizations to better anchor fishery resources and wealth locally.6 This interplay between institutional change and spatial transformation jointly influences the effectiveness of community governance.7The development of fishing ports also exerts socioeconomic impacts on surrounding communities, even those not traditionally reliant on fisheries.8 The concept of ‘space’ significantly influences fishers’ livelihoods and activities, encompassing fishing grounds, landing sites, markets, and social integration within destination communities.9 However, existing research offers insufficient exploration of the mechanisms within the FPEZ as a quintessential case of an RIS, with most studies focusing on manufacturing or high-tech industries.

In 2023, the total economic output value of the fishery industry was 3,266.996 billion Yuan, and the fishery population was 15.9857 million, but the per capita net income of fishermen was only 25,777.21 Yuan. The transformation and upgrading of traditional fisheries, an industry with relatively low profits and worker income levels that require improvement, is very urgent.10 In essence, transformation and upgrading consist of a series of micro-innovations in technology, industry, management, and systems. To promote the continuous emergence of these innovations, it is necessary to construct a regional development environment that stimulates endogenous impetus, effectively integrates resources, and fosters spatial interaction, aligning completely with the core concerns of RIS theory. Through the introduction of modern technology and management concepts, new impetus can be injected into the fishery industry, which can not only effectively improve the income level of fishermen but also promote the overall economic development of the fishing harbour economic zone and enhance its added value.

To deeply reveal the “dynamics-governance-space” three-dimensional mechanism of fishing port economic zones and to lay a theoretical foundation for the future introduction of empirical models, this paper, based on RIS theory, constructs a three-dimensional interaction analysis framework. It systematically reviews relevant domestic and foreign literature from 2014-2024, aiming to fill the theoretical gaps in this field in mechanism mining and spatial effect quantification.

1. Scope of literature and its knowledge mapping analysis

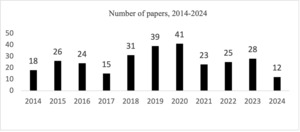

To explore the research progress of fishing port economic zones in depth, this study primarily used the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) journal database and dissertation database, with “fishing port” and “fishing port economic zone” as core search terms. A total of 282 documents were retrieved, comprising 220 academic journal articles, 49 dissertations, and 8 conference papers; their distribution is shown in Figure 1. Relevant policy documents issued by major coastal provinces and cities were also included. The selection of literature is based on aspects corresponding to the D-G-S framework within RIS theory: industrial dynamics and innovation activities (dynamics dimension), policy intervention and governance structure (governance dimension), and spatial agglomeration and regional linkage (spatial dimension). This approach ensures a comprehensive literature foundation for subsequent analysis and systematic review.

As seen in Figure 1, research related to fishing harbor economic zones has an inverted U-shaped development trend. 2018 to 2020 was the peak period for research in this field, with research output reaching its zenith; 41 publications represented the highest annual number, which gradually declined after 2020. Regarding the number of publications, China’s investment in research on fishing port economic zones has been relatively limited.

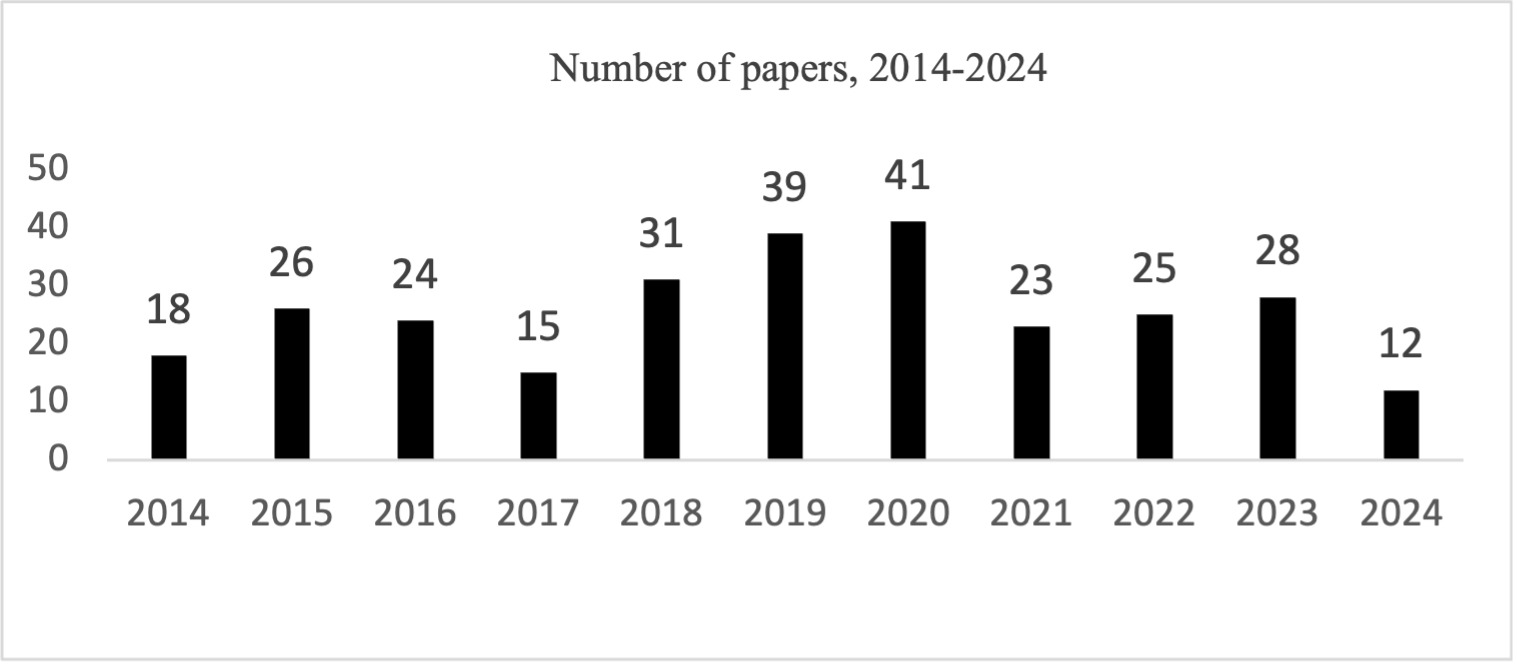

In this study, keyword co-occurrence analysis was conducted on 282 documents using Graphviz programming, and the generated knowledge graph is shown in Figure 2, where the dots represent nouns in the article, and the closer to the center, the more frequently the noun appears in the article. If two nouns are more relevant and appear in the same literature, they are linked by a straight line, indicating that they are often mentioned in sync in the study of fishing port economic zones. The results of the knowledge graph analysis show that:

-

The terms ‘Industry,’ ‘Development,’ ‘Economy,’ and ‘Construction’ form a prominent and densely connected cluster in the hotword network. This configuration highlights the field’s dominant research focus on the foundational pillars of economic growth and infrastructure development.

-

‘Region,’ ‘Area,’ ‘Nation,’ and ‘System’ exhibit a peripheral stance with sparse connections. This indicates a potential analytical void concerning these zones’ broader spatial and systemic integration, underscoring a need for enhanced inquiry into inter-regional synergy and macro-level governance.

-

High word frequencies indicate that ‘Development,’ ‘Construction,’ ‘Economic Zone,’ and ‘Fishery’ are central to scholarly discourse. Their prominence reflects a sustained focus on core growth, infrastructure, and sector-specific themes within the literature.

-

In stark contrast, ‘Model,’ ‘Theory,’ ‘Analysis,’ and ‘Impact’ remain peripheral with minimal network integration. This pattern suggests a discernible gap in rigorous theoretical frameworks, advanced econometric methodologies, and comprehensive quantitative analyses applied to fishing port economic zones.

Visualizing the literature keyword knowledge graph systematically deconstructs the complex knowledge network of fishing port economic zones, providing key insights for constructing the theoretical framework. This study breaks through the traditional single-dimensional analysis, constructs the power-governance-space three-dimensional analysis framework, systematically deconstructs the development mechanism of the fishing port economic zone, and provides support for the economic development and policy formulation of the fishing port economic zone.

Beyond temporal and keyword analyses, a thematic categorization of the reviewed literature identifies key research areas (Figure 3). Studies on infrastructure, technology, and management innovation constitute the largest share (24.14%), followed by macro planning and policy (20.69%), and development models and experience sharing (17.24%). Industrial development and transformation & upgrading (13.79%) and ecological environment and social impact (13.79%) also represent significant proportions. Notably, theoretical and conceptual elaboration accounts for only 10.34% of studies, indicating a relatively practical and policy-oriented research landscape that needs more foundational theoretical work, which our proposed framework aims to address.

Three-dimensional analysis framework construction

Understanding the process of multiple factors interacting with and co-evolving in a specific spatial-temporal context is the basis for analyzing the development of fishing port economic zones, which requires an integrated analytical framework with a multidisciplinary perspective. Although the regional innovation system theory profoundly explains innovation’s systemic, territorial, and system-embedded characteristics (Asheim, 2019),11 its multidimensionality and complexity make it particularly important to construct an analytical framework that includes both the whole and the details. Drawing on an extensive analysis of existing literature and theories from New Institutional Economics, Economic Geography, Complexity Economics, and Management Science, this study proposes the “dynamics-governance-space” three-dimensional framework as a theoretical tool designed to structure the core of RIS theory, integrate multiple theoretical perspectives, and enhance analytical depth.

1. Mechanisms of action in the three dimensions

The dynamics dimension, the core driving force of system development, involves eliminating old production methods and continuously developing high-technology industries as new growth engines, realizing “creative destruction” (or “innovative disruption”). Evolutionary economics also deeply influences this dimension, focusing on the mechanisms of knowledge creation, diffusion, and absorption; the formation and change of technological trajectories; and the emergence of new industries and organizations. This dimension captures the endogenous, non-equilibrium, continuously changing nature of the system. Without the dynamics dimension, the differences in regional economic development cannot be explained, which is equivalent to denying the possibility of system evolution.12,13

The governance dimension is the structural force that guides the direction of the system, examining how to break through the historically formed path dependence through institutional innovation (including the definition of property rights, the reform of the management system, and the optimization of the operation mechanism). Governance theory is also introduced to examine how to design and apply a combination of policy instruments and how to form policy synergies among multiple actors as a way to reduce the internal transaction costs of RIS and provide stable expectations and incentive-compatible environments for its development.14 Without the governance dimension, it is impossible to explain why different regions under the same development conditions produce very different outcomes under different regimes or to specify the boundaries of government management.

The spatial dimension is based on the territorial nature of economic activities and examines the spatial effects produced by each economic entity as a spatial node in the RIS from a dynamic perspective. From the perspectives of economic geography and regional science, it explores interactions within and between specific regions, promoting port-industry-city integration and urban-rural integration. It also focuses on positive externalities such as knowledge spillovers and industrial linkages, as well as negative externalities such as resource competition and environmental pollution. At the spatial scale, it analyses how these effects propagate among economic agents and ultimately impact the development of economic zones. The absence of this dimension ignores the regional attributes of RIS theory and fails to explain agglomeration advantages and spatial imbalances.15

Together, the three form a minimal complete set for analyzing the RIS phenomenon, and the absence of any one dimension can lead to a one-sided understanding of RIS.

2. Interconnections between dimensions

These three dimensions are not isolated but are interdependent, dynamically coupled, and co-evolved. The development of RIS is also not determined by a single dimension but is rooted in the strategic synergy and structural coupling between the three, e.g., innovation efficiency, adaptive capacity, and developmental resilience, which emerges from these three dimensions and their complex interactions. Industrial upgrading within a region promotes innovation in government systems and can reshape the spatial pattern of economic activities. Progress in government governance effectiveness also clears institutional barriers to industrial upgrading and industrial integration and can also promote mutual exchange and cooperation within the space, while spatial characteristics provide innovations in industrial upgrading and governance patterns.16

The upgrading of innovative activities and high-tech industries often requires economic agents to establish new rules of cooperation and governments to introduce new policies to accommodate productivity development. The rapid development of innovative activities also exposes the inadequacies of existing governance systems, thus triggering the need for governance change. Policies such as intellectual property laws, financing policies, and development plans can directly promote innovation, enhance knowledge flow, and unlock innovative potential. On the contrary, inappropriate systems can also limit the dynamism of economic zones.17

Effective governance and institutions can shape spatial structures with high economic efficiency and promote innovation by influencing investment and regional planning, while rigid institutions can lead to spatial misallocation of resources, thereby inhibiting the dynamics of economic development. At the same time, investment in transport facilities can also affect regional connectivity, which further affects economic exchanges and innovative activities between regions; different regions have different endowments, which limits the space and direction of policy operations; and different topographies can also impede coordinated governance across regions.18

Specific spatial deconstruction affects the efficiency of knowledge spillovers and patterns of innovative cooperation. Geographic proximity inevitably leads to the sharing of specialized labor, infrastructure, and suppliers, facilitating tacit knowledge spillovers and face-to-face exchanges, promoting healthy competition among economic individuals, and stimulating innovation dynamics. Conversely, the rise of new industries can challenge the inherent geographic structure, leading to industrial clusters and agglomerations, and innovative activities may also exacerbate local pollution and create negative externalities by disrupting the local business environment.19

To sum up, the “dynamics-governance-space” three-dimensional framework deconstructs RIS theory, ensuring comprehensiveness at the macro level while considering depth at the micro level. It possesses an authoritative theoretical background and solid analytical logic, representing a theoretical self-awareness and analytical strategy rooted in a profound understanding of the inherent structure and operational logic of complex socio-economic systems. It is a theoretical consciousness and analytical strategy based on a profound knowledge of the inner structure and operating logic of complex socio-economic systems. It has scientifically answered the three basic questions of how the system changes, how the system is organized and coordinated, and where and how the system is related, while other questions such as “technology”, “culture”, “network” or “globalization” have been answered. Other focal points such as “technology”, “culture”, “networks” or “globalization” can be classified as one of the three questions or be addressed by the three dimensions together. The schematic diagram of the dynamics-governance-space three-dimensional analysis framework is shown in Figure 4. This study will use this framework to analyze the results of the research on fishing port economic zones in the last 10 years.

3. Advantages of This Framework

This study’s core contribution is the innovative D-G-S framework, which systematically deconstructs Fishing Port Economic Zones (FPEZs) within a dynamically coupled Regional Innovation System (RIS) paradigm. Integrating insights from regional, institutional, and industrial/evolutionary economics, it addresses fragmented understandings of FPEZ complexity. The framework elucidates FPEZs’ unique evolutionary logic as resource-dependent regions, achieving ‘creative destruction’ and ‘path creation’ through dynamics, governance, and space interplay. Its structured analysis enhances theoretical operationalization, providing a robust foundation for future quantitative analysis and precise policy interventions in FPEZ development.

Analysis of the three-dimensional framework for the development of fishing port economic zones

Materials and Methods

Fishing port economic zones are not simply a collection of industries and economic activities, but a complex regional economic system that drives innovation and economic transformation in a broad sense. Its development is essentially about three dimensions, namely, how to stimulate endogenous industrial growth and structural upgrading (the dynamics dimension), how to design effective rules and coordinate multiple actors (the governance dimension), and how to take advantage of geography and manage spatial linkages (the spatial dimension). Other theoretical frameworks, such as Spatial Economics and public policy, although each has its strengths, are limited to portraying certain aspects of the fishing port economic zone, and are unable to capture the complex multidimensional coupling within the economic zone, whereas the “dynamics-governance-space” three-dimensional framework focuses on the synergistic evolution and interactions, which is in line with the complexity and multidimensionality of the fishing port economic zone.20,21

1.1. Driving force for development: industrial upgrading and innovation drive

From the perspective of RIS theory, the dynamics dimension serves as the core endogenous driving force for increasing the value-added of fishing port economic zones, stemming from diversified innovation activities and the strategic evolution of industrial structure. This dimension primarily focuses on the inherent driving forces, evolutionary mechanisms, and innovation activities within the RIS itself, encompassing the transformative development of industries such as advanced aquatic product processing, leisure fishery, coastal tourism, cold chain logistics, and ship repair. Based on this, our analysis of the FPEZ literature reveals that while industrial upgrading and the integration of the three industries demonstrably drive growth, they frequently encounter significant challenges in knowledge transfer and structural optimization. From an RIS lens, these challenges are not merely operational hurdles; they fundamentally reflect bottlenecks in the regional innovation ecosystem’s absorptive capacity and the inherent friction of ‘creative destruction’ as FPEZs attempt to transcend traditional production paradigms. Specifically, persistent difficulties in knowledge transfer signify gaps in the pathways for effective knowledge diffusion and absorption among various actors, thereby hindering the application of new technologies and expertise. Similarly, challenges in structural optimization point to the inertia in reallocating resources from declining to emerging high-value-added sectors, a critical process for sustainable RIS evolution.

1.1. Transformation of traditional fisheries: from fishing to further processing

The breakthrough of fishing port economic zones from the low value-added dilemma must depend on the completion of industrial upgrading. Based on Schumpeter’s theory of industrial life cycle, the evolution of fishing port economic zones can be divided into start-up, growth, maturity, and transition (see Table 1 for details). The transformation of Fishing Port Economic Zones (FPEZs) from primary fishing to deep processing and tertiary industry integration is not merely an optimization of industrial structure; it represents a profound process of “creative destruction” within their Regional Innovation System. As articulated by Schumpeter, this shift demands the elimination of outdated empirical production methods and knowledge systems, replaced by the formation of new industrial clusters centered on technological, standard, and management innovation. This activation of new growth drivers, in turn, propels the economic zone towards high-quality development. Existing research focuses on the extension of the industry chain from traditional aquatic fishing to deep processing of aquatic products and fishing port-related services in fishing port economic zones. Scholars have analyzed the cases of Zhoushan in Zhejiang Province and Rongcheng in Shandong Province, and found that infrastructure renewal, advancement of processing technology, and improvement of labor quality are the three carriages of industrial transformation and upgrading, and pointed out that the imbalance of industrial structure and industry chain faults are the main bottlenecks at present, and it is necessary to optimize the allocation of resources through the guidance of policies. From the perspective of RIS theory, industrial transformation is not a simple lengthening of the industrial chain, but a structural change within the deep regional innovation system, which requires upgrading in terms of knowledge, actor-network, and industrial environment.

Progress from primary fishing operations to intensive processing essentially implies the transformation of knowledge systems from empirical to technical and standardized (see Table 2). It imposes requirements on regional workers and enterprises to leapfrog in terms of technology absorption capacity and the ability to acquire external knowledge. If workers and enterprises in the economic zone are unable to meet the requirements, they are unable to accumulate sufficient knowledge capacity, which will result in industrial upgrading not taking place. The leapfrogging must be accompanied by a drive to form closer and more complex relationships of cooperation and competition among subjects such as fishermen, workers, processors, operators, financial institutions, and technical service organizations. The construction and optimization of such networks are the basis for improving overall efficiency and innovation. Existing studies also confirm the benefits generated by systemic transformation with its process complexity22 who calculated that the improvement of industrial structure has significantly improved the per capita output as well as employee well-being in the fishing port economic zone by means of panel analysis, but at the same time it is also necessary to dynamically adjust the relationship between advancement and moderate scaling, so as to avoid the crowding out of low-skilled by upgrading of industrial structure labor force,22,23 Yuan and Qian (2012)24 and others use computable general equilibrium model to reveal that at the current stage, we should focus on the development of processing industry, service industry and other labor-intensive industries, which is more conducive to the economic growth of the fishing port economic zone ,24 Lew and Seung (2020)25 analyzed the importance of the development of the recreational fishery of the Alaska seaport to the local fishery economy through the re-sampling method. Development as an important contribution to the local fisheries economy.25 Wei (2018) and others proposed the need to strengthen top-level design and integrated planning, focusing on breaking through policy barriers to optimize the development environment and clarifying the necessity of systematic top-level design,26 and Li (2017) and Ou et al (2017) and others proposed methods to carry out scientific industrial positioning, upgrading and layout, which reflects the need to proactively plan and guide the direction of knowledge accumulation in practice with the construction of new actor networks.27,28 Dong et al. (2019) pointed out that China’s fishing port economic zones generally have the problems of unbalanced industrial structure, incomplete industrial chain, and unremarkable industrial benefits, emphasizing the key role of optimizing industrial layout in promoting the quality, efficiency, transformation, and upgrading of the fishery industry.29 Wang (2023) and others pointed out that updating port infrastructure and optimizing the service effectiveness of economic zone management level is the solid foundation for transformation .30

The above studies cover the positioning, design, aggregation and resource utilization of fishing port economic zones, but most of them lack the tracking of dynamic processes. In the future, the synergistic evolution of knowledge, networks, institutions, and infrastructures in fishing port economic zones can be further studied in conjunction with evolutionary economic geography, and only the synergistic evolution is the manifestation of the improvement of the overall capacity of the regional innovation system.

1.2. Expanding dynamics: mechanisms for triple production integration

From the perspective of RIS theory, cross-border integration between industries is a profound systemic change. The core mechanism for its success lies in promoting effective synergy and knowledge integration among cross-sectoral and cross-disciplinary actors and improving the key dynamics of overall system effectiveness. These high-level industries can internalize the fishing industry as a component of high-end industries, vertically drive the development of low-end industries, improve the competitiveness of fishing port economic zones, and shift from reliance on a single fishery resource to a synergistic symbiosis of multiple industries. Eventually, a new value network and regional core competitiveness will be formed.

The significant positive effects brought about by the integration of the three industries have been brought to the attention of various scholars. Studies have emphasized that through the development of modern service industries such as cold chain logistics, special culture and tourism, and fishing port finance, significant synergistic effects can be created with the fishing, aquaculture, and processing industries, increasing the comprehensive added value of each industry, forming a higher level of industrial ecology, and facilitating the development of fishing port economic zones. Some regional development strategy studies, such as analyses of Guangdong’s coastal zone, regard the development of tertiary industries, such as coastal tourism, and the construction of deep-water ports (to support modern logistics), as key initiatives for balancing economic development and ecological protection, and for promoting regional co-ordination .31 The results of econometric studies from Alaska also show that commercial fishing has a significant promotion effect on the coastal processing industry, and service industry .32 Lin et al (2022)33 pointed out the need for well-developed industrial parks, supporting cold chains, and marketing services that can make economically lucrative pelagic farming possible. The practice has proved that the construction of a closely linked fishery-processing-service value network has a significant pulling effect on the regional economy .34 This pulling effect is not a single linear pull, the results of econometric analyses of the integration of leisure fisheries and other industries show that there is a complex u-shaped relationship between the pulling effect and the growth of per capita income in fishing port economic zones, and the spatial differentiation of the specific effects is obvious, which implies that the promotion of the integration requires a differentiated strategy tailored to the local conditions, rather than "one size fits all.35 In this context, the use of modern technologies should be strengthened by actively building intelligent monitoring, information interconnection, integrated management economic service platforms, etc.36,37 These emerging technologies can solidly support efficient cross-industry collaboration, service innovation, and other key growth factors.

Promoting industrial integration likewise faces several systemic barriers. Firstly, there are hard barriers such as backward infrastructure and insufficient land and industrial facilities.34 Secondly, some studies have made more specific diagnoses by constructing an indicator system, such as Zhu et al.'s (2019) analysis of Guangxi’s marine fishing villages, which found that lagging road transport conditions, weak agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery service bases, and imperfect power grid facilities have all become specific obstacle factors restricting the integration of the three industries, which require targeted development of characteristic new industries and strengthening of infrastructure construction.38 All these studies confirm the above view that the shortcomings of infrastructure and service capacity affect the flow of production factors, knowledge, and information among economic agents, and impede inter-industry interaction. At the same time, the organizational inertia and path dependence brought about by the long-standing problem of functional homogenization of fishing ports in China, as well as the lack of sufficient culture among fishermen, fishing ports have the problems of “fewer harbors, smaller harbors, weaker harbors, and poorer harbors”, which impede the integration of regional industries, and the free flow of institutions and human capital.39

In conclusion, although integrating the three industries is a key power mechanism and an important evolutionary path to driving the development of fishing port economic zones, existing research lacks quantitative assessment studies of the integration effect. In the future, the structural characteristics of industrial linkages can be analyzed through subject network analysis and relationship-oriented social network analysis (SNA).

2. Governance dimensions: policy, synergy, and institutional innovation

Within the comprehensive Regional Innovation System (RIS) framework, the governance dimension stands as the crucial orchestrator of coordination, guidance, regulation, and institutional arrangements that profoundly shape the behavior of innovation actors and the overall efficiency of FPEZs. This dimension extends beyond governmental policy power (e.g., land-use planning, financial subsidies, environmental regulation) to encompass the broader efficacy of institutional innovations essential for system functionality. For FPEZs, effective governance is not merely administrative oversight; it is pivotal in mitigating path dependence, facilitating vital knowledge flows (linking to the dynamics dimension), and enabling the optimal spatial allocation of resources (linking to the space dimension). This section will therefore delve into the institutional landscape of FPEZs, analyzing the inherent challenges – such as institutional rigidity and fragmented coordination – that often impede their transformative potential and innovative performance. It will further explore how strategically optimized governance mechanisms can serve as catalysts for sustainable development

2.1. Institutional Path Dependence: Breaking Through Institutional Inertia and Path Dependence

The theory of institutional change suggests that institutional change in an economy and society has its inherent inertia, and that fishing port economic zones have generated a dependence on past institutions and will continue to maintain such a trajectory of development. Studies by Ping (2019) and Peng (2023), analyzing policy changes from a Sino-US comparative and historical perspective, found that China’s fishing port policy has significant issues of prioritizing infrastructure over management, shaping current governance landscapes and challenges.40,41

To overcome the inertia of government domination, it is necessary to reconstruct the rights and responsibilities of the main parties and introduce a pluralistic governance system. Hu Jing (2024)42 et al. found through comparative research that fishing villages with high social capital are more synergistic in environmental governance and have better governance results, and social capital and professional management capacity can be introduced through modes such as BOT, PPP and other modes (Peng, 2023). Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan have introduced policies to bring in private capital to participate in management, especially for operational or partially public welfare facilities, to expand funding sources and improve management efficiency. Zhejiang has also reclassified land and waters at the county level, and has clarified the rights and responsibilities of different subjects.43–46 Taiwan has proposed infrastructure, industrial upgrading policies while emphasizing the protection of fishermen’s rights and interests. These practices are innovations in financing methods while improving management efficiency and expanding sources of capital, and at a deeper level, they are profound changes in property rights reform, incentive mechanism design, and pluralistic governance.47

To overcome the lack of institutional supply, continuous institutional innovation is needed to optimize the environment. Li Yang et al. take rural revitalization as the general background and put forward a strategic framework and top-level design of fishing port economic zones suitable for this strategy (Li et al, 2022), pointing out that systematic institutional changes should be carried out in the areas of factor guarantee, investment and financing, and mechanism innovation (Wei, 2018), to support the sustainable development and functional upgrading of the fishing port economic zones.48–52 Clear property rights, effective governance structure, and lower transaction costs are the key institutional elements to optimize the development model of fishing port economic zones.53

The policy objective of promoting industrial upgrading is constrained by path dependence in reality, and the actual situation is not as expected. (Maya-Jariego et al.2016) found that the social network structure plays a great role in resource management and policy implementation, and the policy evaluation should combine network analysis and stakeholder analysis, and the effect of purely public infrastructure investment on industrial upgrading may be limited.54 This suggests that in the construction of fishing port economic zones, it is necessary to pay attention not only to the infrastructure but also to the design of the “soft environment” such as institution building.

Cross-regional heterogeneity in informal institutions, and policy effects has been understudied in existing research. What is certain, however, is that a profound reconfiguration of authority and responsibility, institutional innovation and environmental optimization at the governance level are needed to break out of the historically shaped institutional path dependency.

2.2. Innovation in policy instruments: policy instrument optimization and digital governance

In addition to the focus on institutional innovation, effective fishing port economic zones require innovation in governance instruments and policy tools. Particularly in modern times, where artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and 5G technologies are more mature, digital transformation with these technologies offers new possibilities for improving governance capacity and optimizing the mix of policy tools.

Constructing a digital platform integrating intelligent monitoring, information interconnection, comprehensive management, and other functions is an important way to enhance the effectiveness of governance, which can monitor the operation status of each system, enhance the risk warning ability, and improve the efficiency of public services.55,56 This update of technical equipment improves the regulatory efficiency of the fishing port economic zone, meets the core requirements such as completeness of basic information and scientific functional layout, and achieves a balance between foresight and effectiveness through the “1+1+diverse model” (core leadership + platform support + diverse expansion).57

Optimization of strategic concepts and policy tools is also an important aspect of governance innovation. He (2021) analyzed fishery ecological ethics, social ethics, and industrial ethics from the perspective of economic ethics, and put forward the optimization of tools for fishery management decision-making through an ethical analysis matrix, emphasizing multi-policy synergy.58 Precise strategic positioning and spatial planning have become important tools in local practice. For example, the Tianjin central fishing port has clearly defined the industrial positioning of creating a northern cold-chain logistics and aquatic products processing distribution center and a yacht industry center, and designed an industrial system; Hainan has formulated a three-step implementation procedure and a spatial layout strategy of one nucleus, two belts, and three districts; and Jiangsu, focusing on the synergistic development of coastal fishing port clusters, has proposed an overall layout of “one belt, three clusters, and nine districts”. Meanwhile, (Liang, 2014) and others proposed that the construction of fishing port economic zones needs to follow the concepts of coordinated development and green development, and achieve sustainable development through the optimization of technological efficiency and the abatement of fishing capacity ,59 and Wang (2019) proposed that the sustainable development of fishing harbors should be realized through the policy of fishermen, the restriction of fishery fishing and the policy of resource conservation,60 and the construction of fishing harbors covering intelligence, peace, green, industry, and humanities in five aspects of a comprehensive fishing port economic zone, requiring the choice and combination of policy tools to pay more attention to comprehensive benefits and sustainability, such as internalizing eco-environmental considerations (Zheng, 2022)61 into governance frameworks and policy assessments.

International cases also provide lessons for governance innovation, with experiences from Egypt and Indonesia showing that poor governance mechanisms and lack of infrastructure and data are common challenges constraining the development of fishing ports,62–64 reflecting the importance of modernization of governance capacity and information infrastructure. However, the application of new technologies may also create problems in terms of differences in the ability of different regions and subjects to benefit from digital transformation, which may exacerbate inequality, a new challenge that governance innovation needs to focus on and address.

The governance of fishing port economic zones can evolve towards a smarter, more synergistic, and sustainable direction through digital transformation and continuous optimization of policy tools, which requires matching technological advances with institutional design, always keeping an eye on new issues arising from the misalignment of the two.65

3. Spatial effects: regional linkages and externalities

Studying innovative activities in RIS requires in-depth analyses of the specific geographic space in which they are embedded. Therefore, the spatial dimension pays more attention to how the fishing port economic zone as a spatial node is dynamically related to the external environment and how its economic activities generate impacts across boundaries. Existing research focuses on descriptive spatial planning and lacks in-depth quantitative analyses of the heterogeneity of spatial effects as well as the unavoidable negative externalities. Spatial analysis requires an understanding of regional patterns and linkages as a result of the complex interaction of multiple factors such as resource endowments, governance patterns,66 infrastructure levels, market access conditions, and the behavior of micro-entrepreneurs,67 and is often accompanied by both positive and negative spatial spillovers.68

3.1. Spatial agglomeration and regional diffusion: the effect of interaction between port, industry, and cities

This section first focuses on the first key facet of the spatial effects of FPEZs: that is, how they act as vectors of economic activity that geospatially facilitate the agglomeration of industries and factors and, in turn, through their interaction with neighboring regions, may have a regional diffusion effect on growth.

The spatial mechanism of fishing port economic zones allows for the development of competitive advantages locally through agglomeration economies and the diffusion of such advantages to the wider region through effective linkage channels. Specifically, the concentration of industries within the economic zone contributes to economies of scale at the port level, and actors based on geographical proximity can give rise to positive spillovers of cooperation. However, there is significant heterogeneity in the effects of agglomeration advantages, which are influenced by the “port-industry-city” interaction mechanism between the fishing port economic zone and the city center.

The role of agglomeration economies in the development of fishing ports was confirmed in a study by Speir and Lee (2021),68 where economies of scale in the processing and marketing segments were an important force driving the concentration of catch in a few core ports. Long-term tracking of the US Atlantic scallop fishery also found economies of scope in the port industry, with diversified agglomeration favoring increased catches. These reflect the complex dynamics associated with agglomeration. In addition to increased economic efficiency, agglomeration also promotes cooperation, Lu (2021) found that fishing vessels sharing the same major port exhibited the strongest positive spillover effects among them, which may stem from the fact that geographic proximity promotes cooperative behaviours, such as information sharing and resource coordination, a phenomenon that is typically found in Dongtou’s Fishing Harbour Economic Zone.69 Existing studies have shown that fishing port economic zones breed development potential through spatial agglomeration but may not be able to play the role of a growth pole. In the future, spatial econometric models (e.g. GWR) and complex network theory can be used to grasp the complex interaction between agglomeration and diffusion accurately.

3.2. Network connectivity and spatial externalities: cross-regional impact analysis

In addition to local agglomeration and diffusion, the spatial effect of FPEZs is more reflected in their integration into regional and even wider network systems as open nodes, and through such network connectivity they generate cross-regional impacts, which are inevitably accompanied by spatial externalities. In RIS theory, the fishing port economic zone is a key node embedded in a multi-scale network, and its development depends on the efficiency and quality of the exchange of material, information, knowledge, capital, and other factors with external regions. Such network connectivity not only brings development opportunities, but also inevitably generates spillover effects or externalities across administrative boundaries.

The importance of network connectivity at the macro level is reflected in the fact that effective resource reallocation and cross-area synergies rely on the support of logistics, information, and institutional networks,70 and at the micro level in the fact that the choice of which ports to use by fishermen or fleets is affected by a complex mix of multiple factors, such as harbour infrastructure, market access, catch prices, distance to fishing grounds, and their characteristics. Governance decisions (e.g., the implementation of the ITQ system) can profoundly change this network connectivity pattern, forming a port integration phenomenon in which fishing activities, and industries are clustered in a small number of fishing harbors, such as the Nan’ao Island Fishing Harbour Economic Zone, which develops the tourism industry through its specific advantages, and realizes the docking of the regional tourism network and its own upgrading.71 International case studies also show that port-industry-city (village) integration is an important model for enhancing spatial integration efficiency.72,73 However, network connectivity has positive externalities such as knowledge spillovers and industrial linkages on the one hand; on the other hand, it may also generate negative externalities, such as cross-border impacts of environmental pollution and negative effects due to intensified competition for resources - even in harbors where co-operation exists, an increase in the intensity of peer fishing may still have a negative impact on individual incomes. Quantitative research and assessment of the spatial manifestation of positive and negative externalities remains a direction that needs to be strengthened in future research.74

The spatial effects of fishing port economic zones can be understood only in the context of open, multi-scale networks, to analyze the mechanisms, efficiency, and patterns of network connectivity and systematically assess the complex spatial externalities they generate. Current research has not sufficiently analyzed the “black box” mechanism of factor mobility and especially lacks an examination of non-economic factors (e.g., ecological compensation, cultural identity).

Summary and outlook

This paper presents a systematic review of research on the development of China’s fishing port economic zones (FPEZs) over the past decade, using the regional innovation system (RIS) theoretical perspective and the integrated “dynamics-governance-space” (D-G-S) framework. Rather than presenting the characteristics of each dimension in isolation, the core finding of the study reveals that the development of FPEZs is essentially an evolutionary process of complex interactions and mutual shaping among the three dimensions of dynamics, governance, and space. Specifically, the analysis and research through the existing literature review shows that:

(1) The effectiveness of efforts to stimulate industrial upgrading and innovation (dynamics dimension) depends on whether effective policy coordination and institutional innovation (governance dimension) can break through historical path dependence and is supported or constrained by appropriate spatial structure and network connectivity (spatial dimension). Current research has pointed out that inadequate assessment of the effectiveness of governance mechanisms and unclear perception of spatial effects (e.g., heterogeneity, externalities) are key shortcomings.

(2) To avoid planning failures or resource mismatches, the exploration of governance models (e.g., the introduction of social capital, digital management), and the layout of spatial strategies (e.g., port-industry-city integration, and regional linkages) must be matched with the region’s endogenous innovation capacity and knowledge base (dynamics dimension).

Therefore, the main contributions of this study are: first, at the theoretical level, through the application of the D-G-S framework, it highlights the importance of grasping the interdependence of dimensions and the feedback mechanism when understanding a complex system such as the FPEZ, transcending the limitations of a single entry point; and second, at the practical level, it provides policymakers with a means of identifying systematic bottlenecks (often present at dimensional interfaces) and conducting holistic policy design through a comprehensive knowledge map, thus more effectively serving the national maritime power strategy and rural revitalization strategies.

However, what is most striking about existing research is the systematic lack of empirical studies, especially quantitative analyses. Whether assessing the effectiveness of policy instruments, measuring spatial spillover effects, or quantifying the contribution of innovation activities, there are few rigorous analyses based on reliable data, limiting the quantitative grasp of the development patterns of fishing port economic zones, partly because of the difficulty of obtaining relevant data. At the same time, there is still room for improvement in the depth of theoretical discussion, such as the detailed examination of informal systems and the game of subjects in the process of governance, the in-depth analysis of the mechanism of fostering innovation ecosystems, and the attention to the flow of non-economic factors in spatial interactions, which is not yet common.

Because of the above shortcomings, future research on fishing port economic zones can seek breakthroughs in methodological innovation and topic expansion. On the one hand, the enrichment and deepening of methodology is the key direction. We should strongly advocate the organic combination of quantitative and qualitative research, actively explore the potential of spatial econometric modeling in revealing spatial dependence and heterogeneity, use quasi-experimental design to assess the effects of policies in detail, and deepen the understanding of the complex mechanisms and evolutionary processes with the help of tools such as QCA, SNA, ABM, and so on. On the other hand, the expansion of research topics is also crucia.75 Based on the findings of the literature review, this study proposes the following four research propositions:

Proposition 1: In a Fishing Port Economic Zone (FPEZ), institutional innovations aimed at reducing the costs of knowledge acquisition and diffusion (such as the refinement of industry-academia-research collaboration mechanisms and the construction of digital governance platforms) will have a significant positive impact on the knowledge conversion efficiency of its high-value-added industries (Dynamics Dimension). This effect is moderated by the region’s informal institutions, such as trust and a culture of cooperation.

Proposition 2: During the evolution of an FPEZ, diversified and digital governance models centered on functional zoning, land-use policy optimization, and cross-departmental coordination (Governance Dimension) can effectively promote integrated land-sea development and spatial agglomeration in core functional areas. This, in turn, significantly enhances the spatial allocation efficiency of regional innovation factors (Space Dimension).

Proposition 3: Within an FPEZ, as the proportion of deep processing and modern service industries increases (Dynamics Dimension), the degree of internal industrial spatial agglomeration will be significantly enhanced, accompanied by an increase in knowledge spillover effects. However, without effective environmental regulations and spatial planning, the agglomeration resulting from industrial upgrading may also exacerbate negative externalities, such as environmental pollution and the over-exploitation of resources.

Proposition 4: An FPEZ’s degree of path dependence on traditional development models will negatively moderate the promotional effect of institutional innovation (Governance Dimension) on industrial structure optimization (Dynamics Dimension). Meanwhile, the level of development of emerging infrastructure (such as smart ports and logistics networks) in the Space Dimension will positively enhance the FPEZ’s systemic resilience to external shocks.

Sustained efforts in these directions are expected to contribute to building a more complete theoretical framework for FPEZs and provide more solid and powerful scientific support for promoting their transition toward a higher-quality and more sustainable stage of development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs Financial Projects. The funded projects are D220150.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Chao Lyu (Lead). Data curation: Chao Lyu (Equal), Yong Zhu (Equal). Project administration: Chao Lyu (Lead). Formal Analysis: Chao Lyu (Equal), Xiang Li (Equal). Investigation: Chao Lyu (Equal), Xiang Li (Equal). Writing – review & editing: Chao Lyu (Lead). Supervision: Chao Lyu (Equal), Yong Zhu (Equal). Software: Xiang Li (Lead). Methodology: Xiang Li (Lead). Validation: Xiang Li (Lead). Visualization: Xiang Li (Lead). Writing – original draft: Xiang Li (Lead). Funding acquisition: Yong Zhu (Lead). Resources: Yong Zhu (Lead).

Competing of Interest – COPE

No competing interests were disclosed.

Ethical Conduct Approval – IACUC

This study did not involve human or animal subjects, and thus, no ethical approval was required. The study protocol adhered to the guidelines established by the journal.

Informed Consent Statement

All authors and institutions have confirmed this manuscript for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All are available upon reasonable request.

.png)

.png)