INTRODUCTION

Apostichopus japonicus, a common species of sea cucumber, holds significant nutritional and medicinal value and is naturally distributed along the northwestern Pacific coastline.1,2 In China, A. japonicus is one of the highest-yielding species in marine aquaculture, with major production hubs located in Liaoning, Hebei, Shandong, and Fujian provinces.3 As of 2023, China’s A. japonicus aquaculture area expanded to 289,000 ha (hectares), generating an output of approximately 292,000 t and approaching a total market value of 100 billion yuan.4 The primary aquaculture systems for A. japonicus include bottom seeding and proliferation, cofferdam culture, pond culture, industrialized systems, and raft or cage-based cultivation.5,6 Among these, industrialized aquaculture enables precise control of critical environmental parameters - such as water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and overall water quality - allowing for high-density rearing within greenhouse settings. This approach accelerates growth and shortens the production cycle, making it especially suitable for cultivating large juvenile and adult sea cucumbers.7,8 Hebei Province leads China in industrialized A. japonicus aquaculture by both cultivation area and total yield. Key production zones include Changli County (Qinhuangdao City), Caofeidian District, and Laoting County (Tangshan City). The province hosts an estimated 4 million m3 of aquaculture water, supplying nearly 80% of the country’s large-sized juvenile A. japonicus. Industrial overwintering cultivation represents the final stage of seedling production and involves routine operations such as feeding, application of animal health products, and periodic pond transfers. Pond transfer is a critical management practice that helps maintain stable water quality during overwintering. Farmers typically adopt a 15-day interval between transfers, repeating the cycle throughout the overwintering period to ensure optimal rearing conditions.

As aquaculture operations expand and breeding densities rise, the ecological load on water bodies often exceeds their natural capacity for purification and recovery. This imbalance can cause marked changes in water quality parameters, including reduced dissolved oxygen levels, greater pH fluctuations, and elevated concentrations of harmful substances such as ammonia nitrogen, nitrite, and nitrate.9 The accumulation of these toxic compounds destabilizes water quality and severely impairs the growth, health, and survival of cultured species, with potential for mass mortality events. For example, studies have shown that combined exposure to ammonia nitrogen and nitrite causes significant structural damage to key tissues such as the hepatopancreas and gills in Litopenaeus vannamei.10 Sea cucumber aquaculture is often situated in remote coastal regions, where timely environmental monitoring and disease diagnosis remain challenging. In response to deteriorating water conditions or disease symptoms, farmers frequently resort to indiscriminate drug application. This practice disrupts the ecological balance of nearshore aquatic ecosystems and further degrades farming conditions.11,12

Environmental instability also triggers shifts in microbial composition and abundance within the water column, which can directly affect the gut microbiota of A. japonicus. These fluctuations may compromise host-microbe interactions and increase the risk of pathogenic infections, thereby promoting disease.13,14 Zhang et al.15 employed metagenomic sequencing and intestinal excretion analysis to examine the gut bacterial community of A. japonicus, identifying water quality and diet as key environmental determinants of microbial composition. Their study demonstrated that bacterial communities in the gut are highly responsive to changes in the surrounding aquatic environment. Due to their sensitivity and ecological relevance, bacteria are commonly used as bioindicators for assessing water pollution, with both their biomass and diversity reflecting overall ecosystem health.16,17 Beyond serving as indicators, bacterial communities actively participate in purifying contaminated water. However, shifts in water’s physicochemical properties - such as nutrient load, pH, and oxygen content - can profoundly alter microbial richness and diversity.18 In aquaculture systems, both the structure of microbial communities and water quality exert significant, and often interconnected, effects on the physiology, growth, and disease resistance of cultured species. The health of aquatic organisms is therefore closely tied to fluctuations in environmental parameters and the composition of microbial consortia.19,20 To date, most studies on microbial diversity in A. japonicus aquaculture have focused on traditional pond-based systems, while research on microbial dynamics in factory-based cultivation remains scarce. A comprehensive analysis of water quality parameters and microbial community structure in indoor aquaculture workshops is thus essential for optimizing environmental management and promoting the sustainable development of industrialized A. japonicus farming.

Zheng et al.21 utilized high-throughput sequencing to examine the relationships among pathogen emergence, environmental variables, and gut microbiota within a co-culture system of L. vannamei and Cyprinus carpio. Their analysis revealed that, at identical sampling time points, bacterial communities in bottom sediments displayed significantly greater diversity and species richness than those in the overlying water column (P<0.05). In a separate study, Wang et al.22 conducted seasonal monitoring of microbial community dynamics in Sinonovacula constricta and associated aquaculture pond habitats, also using high-throughput sequencing. They observed that the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in winter water samples was significantly higher compared to other seasons (P<0.01). In contrast, the core functional microbial groups in sediment and the gut microbiota of S. constricta remained stable across seasons (P>0.05), indicating strong ecological resilience and niche specificity. High-throughput sequencing, when combined with advanced bioinformatics, offers precise insights into microbial community structures under in situ conditions. This integrated approach identifies ecological interactions within microbial assemblages and between microorganisms and their environmental condition.23,24

This study selected a representative factory-based A. japonicus breeding workshop in Tangshan City, Hebei Province, as a research site. We collected surface water samples from breeding ponds throughout a complete pond transfer cycle during the overwintering cultivation period of A. japonicus. We measured the physicochemical water quality parameters and applied 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing to assess the diversity and functional profiles of the aquatic microbial community at early, middle, and late stages of the pond transfer process. We also performed correlation analyses between the microbial community composition and environmental factors. This study aims to provide a comprehensive and objective characterization of the temporal changes in physicochemical water parameters and the dynamic shifts in microbial communities during the overwintering phase of juvenile A. japonicus under factory farming conditions. Moreover, our findings offer a theoretical foundation to support the healthy and sustainable development of factory-based overwintering cultivation of A. japonicus in Hebei Province.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SAMPLE COLLECTION

In this study, two representative factory-style sea cucumber farming workshops in Tangshan City, Hebei Province were selected and designated as Workshop 1# and Workshop 2#. The dimensions of the aquaculture pond are as follows: length 6 m, width 3 m, and depth 1.5 m. The water temperature maintained at 10–15℃ from Tangshan City, Hebei Province, salinity 28–32, dissolved oxygen levels above 5 mg·L−1 Considering that farmers commonly implement a 15-day pond water exchange cycle, this study defined the day of water exchange as the early stage, the period of 7–8 days after water exchange as the middle stage, and the day immediately before the next water exchange as the late stage. During each of the early, middle, and late stages of the water exchange cycle, 500 ml seawater samples were collected from the surface layer (approximately 15 cm depth) of each of the three culture ponds in both workshops using sterile water samplers. Within four hours of collection, the samples were filtered through 0.22 μm microporous filter membranes (47 mm diameter; Pall Corporation). The filtered membranes were then stored at -80°C until further processing for DNA extraction and high-throughput sequencing.

ASSESSMENT OF PHYSICOCHEMICAL PARAMETERS FOR WATER QUALITY ANALYSIS

The concentrations of ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N), nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N), and nitrite nitrogen (NO2-N) in the samples were quantified in the laboratory. The NH4-N concentration was determined using the Nessler reagent spectrophotometric method as specified in “Determination of Ammonia Nitrogen in Water Quality - Nessler Reagent Spectrophotometric Method” (HJ 535-2009). The NO2-N concentration was measured by the N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride spectrophotometric method according to “Marine Monitoring Specifications Part 4: Seawater Analysis” (GB 17378.4-2007). The NO3-N concentration was analyzed via the ultraviolet spectrophotometric method following “Methods for Analysis of Groundwater Quality - Part 59: Determination of Nitrate - Ultraviolet Spectrophotometric Method” (DZ/T 0064.59-2021). The suspended solids concentration was measured using the JC-SS-1Z laboratory benchtop suspended solids concentration meter.

DNA EXTRACTION AND HIGH-THROUGHPUT SEQUENCING ANALYSIS

DNA was systematically extracted using the OMEGA Soil DNA Kit. The extracted DNA samples underwent rigorous quality control procedures. The DNA concentration was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm with a Nano Drop 2000 micro-volume spectrophotometer, and the integrity of the extracted DNA was confirmed through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

The extracted DNA was used as the template, and the primers 341F (5′- CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG−3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT−3′) were employed for PCR amplification of the V3-V4 region of the 16S rDNA gene. The resulting PCR products were subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis for quality assessment and subsequently purified using magnetic beads. The purified products were then submitted to Jia’an Jianda Medical Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., where sequencing libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit from Illumina. Following library validation, high-throughput sequencing was conducted on the NovaSeq platform. According to the distribution of ASV/OTU in different samples, the Alpha diversity level of each sample was assessed. Additionally, the adequacy of the sequencing depth was reflected by the rarefaction curve.

BIOINFORMATIC ANALYSIS

The sample sequences were analyzed for diversity using QIIME2 software, encompassing Alpha diversity analysis and UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) hierarchical clustering. Taxonomic profiling was performed to compare the species composition across samples. Based on the taxonomic classification results, LEfSe (Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size) analysis was carried out with a significance threshold of P<0.05 to identify differentially abundant taxa and the size of the LDA effect>2. The functional potential of the microbial community was predicted using PICRUSt2, followed by an in-depth analysis of significantly altered KEGG metabolic pathways.

The top 10 most abundant microbial taxa at both the phylum and genus levels were identified. In conjunction with water quality parameters including NH4-N, NO2-N, and NO3-N, the relationship between the aquatic microbial community structure and environmental factors was analyzed using the RDA (Redundancy Analysis) method implemented in Canoco5.0 software.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The data obtained in this study were presented as mean ± standard error (Mean±SE). Statistical analyses, including one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc multiple comparisons (Duncan’s test), were performed using SPSS 25.0 software. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL INDICATORS OF WATER QUALITY

Table 1 presents the physicochemical parameters of water quality across different stages of tank turnover. In the 1# workshop, NH₄-N concentrations showed no significant variation between the early, middle, and late stages (P > 0.05). However, the highest concentration was recorded during the middle stage, reaching 0.621 mg·L⁻¹. In contrast, the 2# workshop exhibited a marked increase in NH₄-N levels during the late stage, peaking at 1.494 mg·L⁻¹. This value was significantly higher than those observed during both the early and middle stages in the 2# workshop, as well as all stages in the 1# workshop (P < 0.05). For NO₃-N, the concentration in the 1# workshop reached a maximum of 0.224 mg·L⁻¹ during the middle stage. This level was significantly greater than those measured in the early and late stages of the 1# workshop and all stages of the 2# workshop (P < 0.05). In the 2# workshop, NO₃-N levels were highest during the late stage at 0.117 mg·L⁻¹, though the differences across all stages were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). NO₂-N concentrations remained consistent throughout all stages in both workshops, showing no significant differences (P > 0.05). Furthermore, the concentration of suspended solids in surface water increased significantly during the middle and late stages compared to the early stage in both workshops (P < 0.05).

SEQUENCING DATA ANALYSIS

After performing sequence splicing, quality filtering, and additional control steps, we identified a total of 4,783 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) across all microbial samples (Figure 1). Of these, only 55 OTUs were shared among all samples, highlighting considerable microbial diversity.

ASSESSMENT OF SPECIES DIVERSITY WITHIN MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES

We evaluated microbial α-diversity using the Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices across different stages of tank turnover. In Workshop 1#, the early stage exhibited significantly higher richness, as measured by the Chao1 index, compared to the middle and late stages (P < 0.05), with the lowest richness observed in the middle stage (Table 2). Furthermore, both the Shannon and Simpson indices declined markedly during the middle stage, indicating reduced diversity and evenness relative to the early and late stages (P < 0.05). In Workshop 2#, richness and Shannon indices did not differ significantly across the early, middle, and late stages (P > 0.05). However, the Simpson index was significantly lower during the middle stage compared to the early and late stages (P < 0.05), suggesting a transient decrease in community evenness during this period.

INVESTIGATION INTO COMPOSITONS OF MOCROBIAL COMMUNITIES

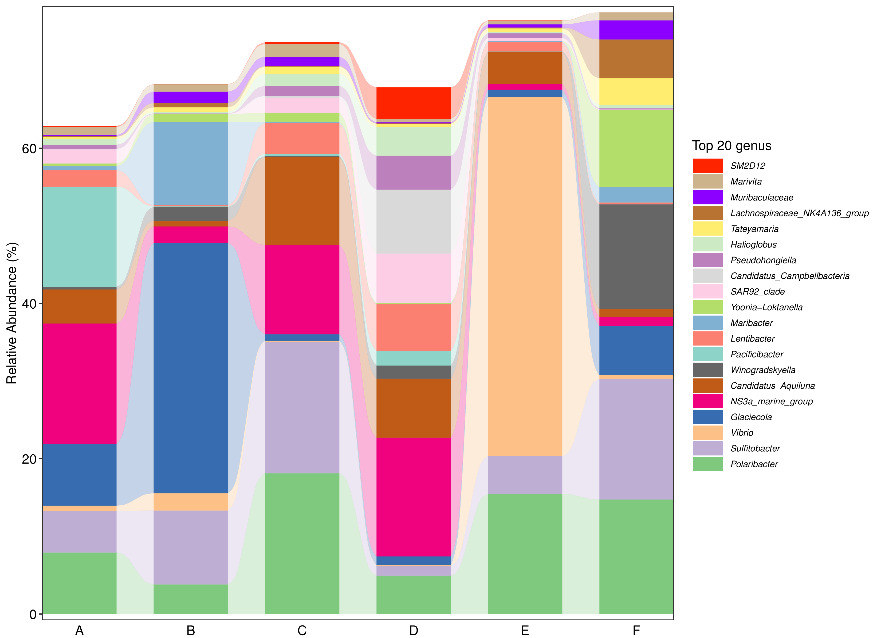

At the phylum level, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes consistently represented the two most dominant groups across all samples. During the early stage of tank turnover, Firmicutes ranked third in abundance in both Workshop 1# and Workshop 2#. However, as turnover progressed to the middle and late stages, Actinobacteria replaced Firmicutes as the third most prevalent phylum (Figure 2). At the genus level (Figure 3), microbial composition varied notably between workshops and turnover stages. In the early stage of tank turnover in Workshop 1#, the three most abundant genera were Glaciecola, Maribacter, and Sulfitobacter, in descending order. In contrast, the early-stage community in Workshop 2# was dominated by Sulfitobacter, Polaribacter, and Winogradskyella. During the middle stage in Workshop 2#, Sulfitobacter remained the most dominant genus, while NS3a_marine_group emerged as the predominant taxon in the late stage. In Workshop 1#, Vibrio dominated the middle stage, comprising more than 40% of the microbial community. This was followed by Polaribacter and Sulfitobacter. By the late stage, the community composition shifted, with NS3a_marine_group becoming the most abundant genus, Polaribacter remaining in second place, and Maribacter ranking third.

CORRELATION ANALYSIS BETWEEN MOCROBIAL COMMINITIES AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTOR

We analyzed the relationship between microbial community composition and environmental variables using redundancy analysis (RDA) in Canoco 5.0. At the phylum level, the first two ordinate axes explained 78.3% of the species-environment variability. The RDA results showed that NH₄-N, NO₂-N, and NO₃-N had no statistically significant influence on the ten most dominant phyla (Figure 4A). However, specific trends were observed: NO₂-N positively associated with Proteobacteria, while NH₄-N and NO₃-N correlated positively with Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobia. In contrast, all three nitrogen forms—NH₄-N, NO₂-N, and NO₃-N—were negatively correlated with Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. At the genus level (Figure 4B), the first twoordinate axes explained 81.8% of the species-environment variability. The top ten genera similarly showed no significant overall response to NH₄-N, NO₂-N, or NO₃-N. Nonetheless, we observed a notable positive correlation between NO₃-N and the genus Vibrio, suggesting a possible genus-specific sensitivity to nitrate levels.

INVESTIGATION INTO STRUCTIRES OF MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES

We used non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) to assess differences in microbial community structures across all samples. The NMDS plots showed clear separations among microbial communities in water samples collected from both workshops at early, middle, and late stages of tank turnover, indicating substantial variations in community composition across time points and locations (Figure 5). We performed linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) to further explore these differences to identify taxa with significantly differential abundances (Figure 6). Among 37 bacterial groups with LDA scores greater than 4.0, six taxa were significantly enriched during the early tank turnover stage in Workshop 1#, including Tenacibaculum, Bacteroidia, Bacteroidales, Flavobacteriales, Flavobacteriaceae, and Maribacter. In contrast, five distinct taxa were enriched during the same stage in Workshop 2#, namely Alteromonadaceae, Glaciecola, Enterobacterales, Gammaproteobacteria, and Clostridiales. During the middle stage of tank turnover, Workshop 1# showed enrichment of five taxa, including Haloferula, Rubritaleaceae, and Verrucomicrobia. By the late stage in Workshop 1#, eight taxa became enriched, such as Proteobacteria, Pseudoalteromonadaceae, Thalassotalea, Litoricola, Litoricolaceae, and Vibrio. In Workshop 2#, the middle turnover stage featured nine enriched taxa, including Cytophagales, Owenweeksia, Cryomorphaceae, Cyclobacteriaceae, Cyclobacterium, Rhodobacterales, and Alphaproteobacteria. Finally, during the late stage in Workshop 2#, four taxa - Polaribacter, Thiotrichales, Leucothrix, and Thiotrichaceae - were significantly enriched.

PREDICTION OF MICROBIAL COMMUNITY FUNCTIONS

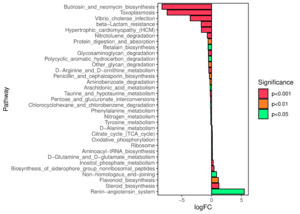

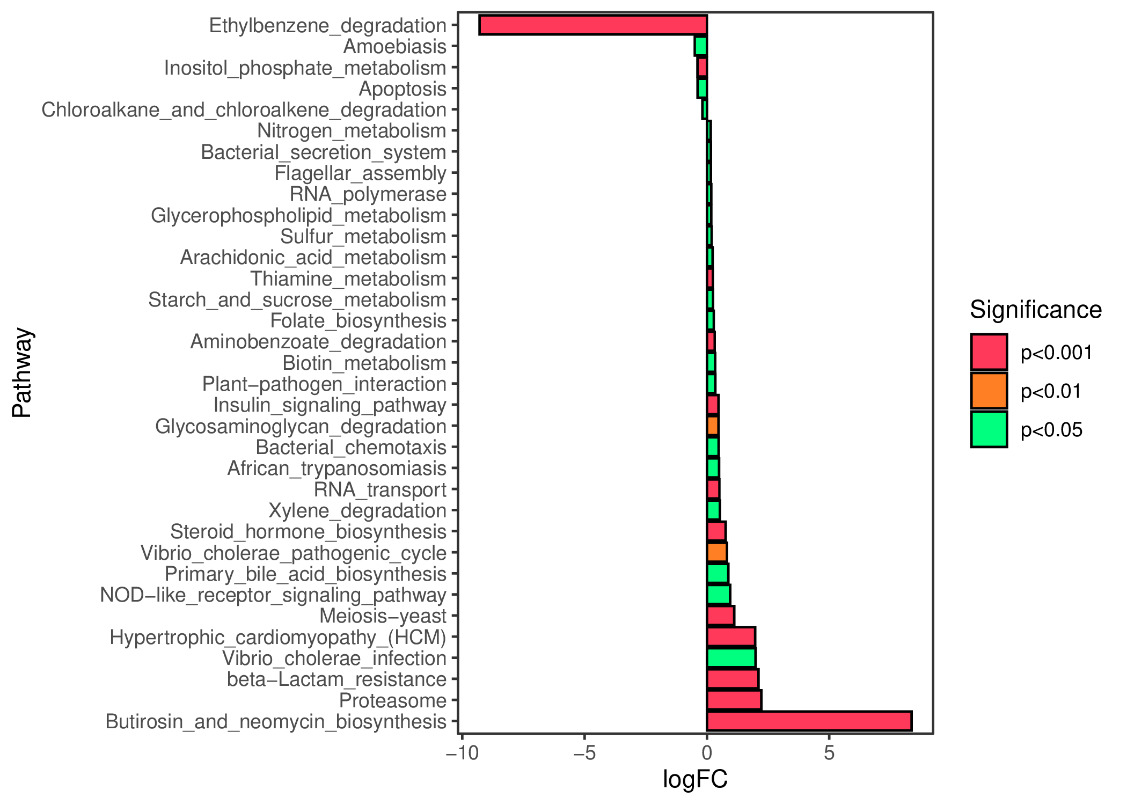

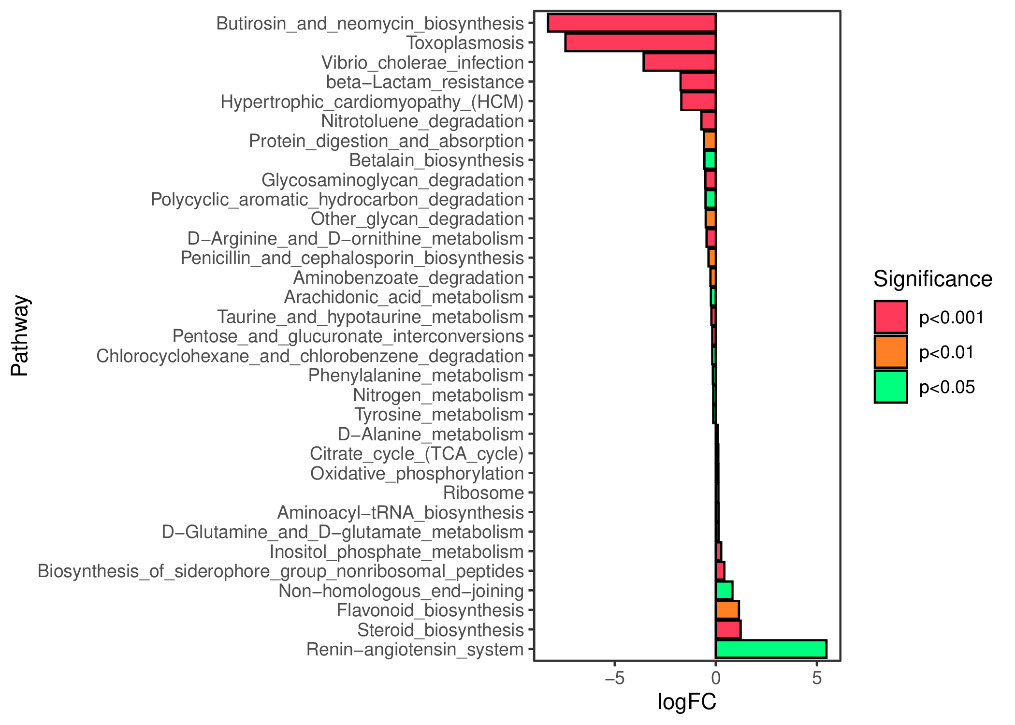

We predicted the KEGG functional profiles of microbial communities during the early and late stages of tank turnover in both workshops using PICRUSt2. We then conducted a detailed analysis of significantly altered metabolic pathways. In Workshop 1#, the microbial community in the late stage of tank turnover showed a marked increase in xenobiotic degradation and metabolism compared to the early stage (P < 0.001). Conversely, pathways related to the biosynthesis of aminoglycosides and neomycin, proteasome function, and β-lactam resistance were significantly downregulated during this period (P < 0.001) (Figure 7). Similarly, in Workshop 2#, the late stage microbial community exhibited a significant upregulation in steroid hormone biosynthesis compared to the early stage (P < 0.05). At the same time, pathways involved in aminoglycoside and neomycin biosynthesis, toxoplasmosis-related processes, and β-lactam resistance were significantly decreased (P < 0.001) (Figure 8).

DISCUSSION

Indoor, factory-based aquaculture systems produce large quantities of organic waste, primarily from uneaten feed and feces. As these materials decompose, they release ammonia nitrogen, nitrate, and nitrite - key pollutants that accumulate in the water. High levels of these nitrogen compounds can impair the immune function of cultured species, disrupt physiological balance, and increase susceptibility to disease or death.25,26 Research has shown that when ammonia nitrogen levels exceed 8 mg·L⁻¹ in aquaculture systems, A. japonicus may develop symptoms such as intestinal expulsion and skin ulceration, which can be fatal.27 Additionally, nitrite concentrations above 4 mg·L⁻¹ reduce antioxidant enzyme activity in A. japonicus, leading to oxidative stress and enhanced lipid peroxidation, both of which are toxic to the organism.28 In our study, ammonia nitrogen levels across all water samples remained between 0.5 and 1.5 mg·L⁻¹, while nitrate and nitrite concentrations consistently stayed below 0.3 mg·L⁻¹. These values fall well within the safety thresholds for A. japonicus aquaculture. Furthermore, based on the National Fishery Water Quality Standards (GB11607-1989) and the Hebei Province “Discharge Standard for Pollutants from Seawater Aquaculture Tail Water” (DB 13/5879—2023), water quality at all sampling locations met both national fishery water quality criteria and the regional discharge regulations for seawater aquaculture effluents.

Microorganisms are essential to aquaculture systems, playing a central role in sustaining water quality and ecosystem stability. Microbial diversity, in particular, is a key factor influencing the resilience and balance of microbial communities.29–31 As benthic organisms, A. japonicus are closely associated with both the water column and sediment in their environment, and their gut microbiota reflects these interactions.32–34 In our study, the richness index of water samples collected during the early stage of tank turnover in Workshop 1# was significantly higher than those from the middle and late stages (P < 0.05). This pattern is consistent with findings by Huang et al.,35 who observed similar microbial community dynamics in seawater from shellfish aquaculture regions. Their research suggests that aquaculture activities may reduce microbial diversity and richness within farming zones. Notably, during the middle stage of tank turnover in Workshop 1#, we recorded the lowest richness index, along with significantly reduced Shannon and Simpson diversity indices when compared to the early and late stages (P < 0.05). This reduction in diversity may be linked to the frequent application of probiotics - such as lactic acid bacteria, yeast, and Bacillus—and disinfectants, which can rapidly alter water conditions and disrupt microbial communities. Microbial composition in aquaculture water is shaped by complex interactions among microbial species as well as various environmental factors.36 However, due to logistical limitations, our sample size was relatively small. Further research with expanded sampling is necessary to validate and extend these findings.

Our study identified Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes as the dominant bacterial phyla in early-stage water samples from both aquaculture tanks during tank turnover. This observation aligns with findings by Tan et al.,37 who reported that in A. japonicus aquaculture ponds in Changhai, Liaoning Province, Proteobacteria was the most abundant phylum, followed by Bacteroidetes, together accounting for over 75% of the microbial population. As the predominant phylum in aquatic ecosystems, Proteobacteria plays a critical role in both molecular and phenotypic classifications of prokaryotes. Members of this phylum are highly adaptable to diverse and extreme environmental conditions and are key contributors to several biogeochemical processes, including denitrification, phosphorus removal, energy metabolism, and the breakdown of organic compounds.38–40 In our samples, Bacteroidetes ranked second in abundance during the early stage of tank turnover. This phylum includes three major classes: Bacteroidia, commonly found in animal intestines and feces, which aids in carbohydrate metabolism; Flavobacteriia, widely distributed in aquatic habitats; and Sphingobacteriia, whose members are capable of degrading cellulose. Notably, we observed negative correlations between the abundance of Bacteroidetes and the concentrations of NH₄-N, NO₂-N, and NO₃-N, suggesting that these nitrogenous toxins may suppress the growth of Bacteroidetes.41–43 In addition, Actinobacteria emerged as the third most abundant phylum in early-stage tank samples, consistent with observations by Xu et al.44 However, in the overall aquaculture water environment, Firmicutes ranked third in abundance. Previous studies have shown that the gut microbiota of aquatic species typically includes Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes. The elevated levels of Firmicutes in the aquaculture water may be linked to overfeeding, which could increase the need for lipid degradation.45–49

In our study, we observed that the dominant bacterial genera during the early stage of tank turnover differed between Workshop 1# and Workshop 2#. This variation likely stems from operational differences in the aquaculture system, particularly the distinct seawater intake locations used by each workshop, which may have introduced site-specific microbial profiles and thus limited comparability. Due to their small size, marine bacteria can disperse extensively, driven by ocean currents. As these microorganisms respond to shifts in water flow and migrate across environments, microbial community compositions often diverge significantly between regions.50

In our study, the phylum Wadinicota showed marked enrichment in water samples collected during the mid-stage of tank turnover in Workshop 1#, coinciding with the highest observed nitrate concentrations. Both NH₄-N and NO₃-N levels positively correlated with the abundance of Wadinicota. This may be due to the metabolic capabilities of certain Wadinicota species, which can fix nitrogen and reduce nitrate and sulfate, thus contributing to various biogeochemical cycles.51 As nitrate levels increased, the relative abundance of Wadinicota also rose. During the late stage of tank turnover in Workshop 1#, the phylum Proteobacteria—specifically taxa from the Pseudoalteromonadaceae family (to the order level) and the genus Vibrio (to the family level)—became dominant. Both Pseudoalteromonas and Vibrio are known to act as opportunistic pathogens in A. japonicus, and we observed a positive correlation between NO₃-N concentration and the abundance of Vibrio.52 As toxic nitrogen compounds accumulated, we detected an increase in the proportion of potentially harmful bacteria. Under intensive aquaculture conditions, the elevated abundance of pathogenic bacteria during the late turnover stage suggests a heightened risk of disease outbreaks associated with high-density farming. To reduce this risk, we recommend shortening the tank turnover cycle or implementing a one-third water exchange strategy during the turnover period, and lower the breeding density.

Microorganisms are integral to key biogeochemical processes, including the biosynthesis, transport, and degradation of secondary metabolites. They also participate in essential cellular functions such as transcription, RNA processing, and RNA modification, enabling adaptive responses to environmental fluctuations.53,54 In our study, Firmicutes emerged as the dominant bacterial phylum in the water samples from both Workshop 1# and Workshop 2#, showing a strong association with the down-regulation of β-lactam resistance pathways during the sampling period. Firmicutes is known to serve as an environmental reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes and is often enriched under conditions of environmental stress, such as contamination with heavy metals or prolonged antibiotic exposure.55 β-lactam antibiotics function by inhibiting bacterial cell wall synthesis during active growth, ultimately leading to cell lysis and death.56 The observed down-regulation of β-lactam resistance in our samples may reflect the selective pressure imposed by repeated antibiotic use in the aquaculture environment, which promotes the emergence of resistant bacterial strains. However, the regulatory networks governing this resistance suppression remain complex and require further elucidation through targeted mechanistic studies.

CONCLUSION

During winter cultivation of juvenile A. japonicus in an indoor factory system, concentrations of ammonia nitrogen, nitrate, and nitrite remained low throughout a complete tank turnover cycle, consistently staying within safe limits for sea cucumber farming. We observed that microbial diversity and richness in the water declined during the middle and late stages of tank turnover compared to the early stage. Additionally, the relative abundance of pathogenic bacteria increased in the late stage. This trend highlights the heightened risk of disease outbreaks associated with intensive, high-density indoor aquaculture.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the S&T Program of Hebei (236Z6306G), Hebei Natural Science Foundation (C2025407065), Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department (QN2025130), Scientific Research Foundation of Hebei Normal University of Science & Technology (2024JK005) and Hebei Agriculture Research System HBCT2023220203.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Miaomiao Yao (Equal), Shanshan Yu (Equal), Qinglin Wang (Equal). Methodology: Miaomiao Yao (Equal), Limin Song (Equal), Yibo Wang (Equal).

Writing–original draft: Miaomiao Yao (Equal), Limin Song (Equal), Shanshan Yu (Equal). Formal Analysis: Guoshan Qi (Equal), Qinglin Wang (Equal).

Investigation: Hai Ren (Equal), Zhenping He (Equal), Chunlong Zhao (Equal).

Funding acquisition: Qinglin Wang (Equal), Chunlong Zhao (Equal).

Writing–review & editing: Guoshan Qi (Supporting), Hai Ren (Supporting).

Supervision: Shanshan Yu (Lead).

Competing of Interest – COPE

Authors declared there were no competing financial interests.

Ethical Conduct Approval – IACUC

The College of Marine Resources & Environment, Hebei Normal University of Science & Technology, Qinhuangdao, China approved the experiments.

Informed Consent Statement

All authors and institutions have confirmed this manuscript for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All are available upon reasonable request.