Introduction

Pelodiscus sinensis, also referred to as the CSST, belongs to the family Trionychidae, and genus Pelodiscus. The species demonstrates extensive biogeographical distribution across freshwater habitats in China, indicating high ecological adaptability.1 Notably, CSST is highly valued for its high nutritional value and distinctive flavor.1 CSST also possesses tonic properties and high economic value. These functional traits highlight its importance both in aquaculture and consumer markets.2 Recently, superior breeds and complementary breeding models have been established, accelerating the growth of CSSTs aquaculture industry.2 Consequently, by 2023, the total CSST production reached 4.97×108 kg in China, accounting for 12.01 % of China’s freshwater aquaculture production in 2023.3

However, the rising scale and density of artificial breeding have increased the risk of disease outbreaks, threatening the sustainable development of this industry.2 Common diseases in CSSTs include skin rot, scabs, enteritis, and head shaking.2 Common pathogens include Aeromonas hydrophilia,4 Edwardsiella tarda,5 Aeromonas veronii,6 Bacillus cereus,2 and Bacillus thuringiensis.7 Nonetheless, disease etiology is increasingly complex due to the emergence of novel pathogens, which limit the efficacy of conventional therapeutic approaches. Therefore, accurate pathogen identification is essential for effective disease management.7

In recent studies on aquaculture, antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens affecting the CSST has emerged as a significant concern.8 For instance, Zhen et al. (2024) identified various bacterial isolates from the livers of diseased CSSTs, including Bacillus cereus, Aeromonas veronii, and Aeromonas hydrophila.7 Most isolates were resistant to Bactrim, and some also showed resistance to tetracycline and aminoglycosides. Further molecular analysis detected key antibiotic resistance genes (qnrS2, blaTEM, and blaCTX-M-14), revealing the genetic basis of multidrug resistance in these pathogens. These findings highlight the urgent need for vigilant monitoring and prudent antibiotic use in CSST farming to mitigate the spread of resistant bacterial strains.8

In 2023, a mass mortality event was reported at a CSSTs base in Hubei Province, China. This study examined the pathological features of the diseased CSSTs. The primary causative agent was identified, and antibiotic-based preventive and control measures were implemented. By integrating experimental findings, this study offers a scientific reference for disease detection and prevention in CSSTs, aiming to minimize disease incidence, enhance breeding efficiency, and increase economic benefits for the CSSTs industry.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Diseased CSSTs weighing 300 ± 20 g and displaying abnormal skin conditions and sluggish behavior were procured from a farm in Hubei Province. The CSSTs were transported to the laboratory under low-temperature conditions for pathogen isolation and identification. For comparative analysis, clinically healthy CSSTs, weighing 80±5 g (approximately 3-month-old under intensive greenhouse rearing conditions), were sourced from Hubei Hongwang Ecological Agriculture Co., Ltd. Viral and bacterial pathogen screening were conducted to confirm the health status of these CSSTs. The primers used for detection are listed in Table 1. The clinically healthy CSSTs were temporarily housed in two laboratory aquaria [4.0 m × 2.5 m × 0.8 m (length × width × height)] for controlled pathogenicity challenge experiments. The CSSTs were reared for 14 d at 28±1 °C and fed three times daily at a rate of 2 % of their body weight per day. All experimental protocols were approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of the Yangtze Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (Approval ID: YFI 2023-zhouyong-0516).

Pathogen isolation

Following anesthesia with MS-222 (100 mg/L), the surface of the plastron-carapace junction of the diseased CSSTs was disinfected with 75% ethanol. Approximately 50 mg of liver tissue was aseptically excised and inoculated onto brain heart infusion (BHI) agar plates (HopeBio, Qingdao, China). The samples were incubated under aerobic conditions at 30°C for 24 h in a constant-temperature incubator (Xinmiao, Shanghai, China). Distinct morphotypes were isolated through three consecutive passages via the quadrant streaking method (3 mm spacing) on fresh Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) (HopeBio, Qingdao, China), yielding axenic bacterial cultures.

Morphological characteristics

Bacterial isolates were preserved by inoculation into Trypticase Soy Broth (HopeBio, Qingdao, China) and subsequently cultured at 30 °C in a constant-temperature orbital shaker (Jingqi, Shanghai, China) with continuous agitation at 200 rpm for 24 h. Bacterial suspensions harvested during the logarithmic growth phase were serially diluted, subjected to Gram staining using a commercial kit (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China), and morphologically analyzed under an optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 1000× magnification with oil immersion.9 For ultrastructural analysis, representative colonies were prefixed with 2.5 % glutaraldehyde (Aladdin Biochemical, Shanghai, China), followed by sequential dehydration in an ethanol gradient series (30 %, 50 %, 70 %, 90 %, and absolute ethanol). After critical point drying, specimens were imaged using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (SU8100, Hitachi, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 8 kV.10

Molecular Identification

A bacterial strain was isolated from the liver of diseased CSSTs. Next, its DNA was extracted using a bacterial genome extraction kit (Tiangen, Nanjing, China). The extracted DNA was then amplified by PCR with universal 16S rDNA primers (Table 1). The amplified products were verified by 1.5 % agarose gel electrophoresis. Thereafter, the purified positive PCR products were sequenced. The resulting sequences were then compared against the NCBI GenBank database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast) using the BLAST tool. Finally, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA software (version 11.0.13).

Biochemical identification

The biochemical characteristics of the purified pathogen were tested using the Biolog Automated Microbial Identification System (Biolog, CA, USA). Initially, the cultured strain and those isolated from reinfection experiments were inoculated in IF-A inoculum fluid (Biolog, CA, USA), followed by inoculation of 100 µL aliquots into each well of the GEN III identification plates (Biolog, CA, USA). After 24 h incubation, the plates were placed in the Biolog Microbial Identification System for incubation and automatic identification.11

Virulence gene detection

The virulence-associated genes of the pathogen were detected via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with reference to relevant literature, targeting those involved in adhesion formation (icaA and icaD), the biofilm-associated surface protein gene bhp (biofilm-associated hydrophobin-like protein), insertion sequence 256 (IS256), and the clumping factor gene clfA (clumping factor A). The presence of the methicillin resistance gene mecA (methicillin resistance gene A), thermostable nuclease Nuc, and leukocidin lukS (leukocidin S component) was also examined. Additionally, genes linked to bacterial secretion and transmembrane transport systems, such as expB (export protein B), were analyzed. Detailed primer information is listed in Table 1. Additionally, we used double-distilled water (ddH₂O) as the negative control for the PCR amplification reaction to effectively exclude potential interference from non-specific amplification or environmental contamination in the experimental system on the detection results, thereby ensuring the specificity and reliability of the amplification signal. A total volume of 25 μL PCR reaction mixture was prepared as follows: 1 μL of bacterial DNA, 1 μL of each primer, 9.5 μL of PCR-grade water, and 12.5 μL of PCR Master Mix (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan). The PCR reaction was carried out with a denaturing step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles as follows: 95 °C for 30 sec, annealing for 30 sec, and extension at 72 °C for 60 sec (Annealing temperatures are listed in Table 1). Finally, an elongation step of 10 min at 72 °C was conducted. Bacterial DNA was used as the template, and triplicate PCR amplifications of virulence genes were performed to minimize experimental variability.

Pathogenicity

The pathogenicity of the isolate was determined by injection-based infection experiments on healthy CSSTs. CSSTs aged 26 weeks were assigned to six groups, each comprising 50 individuals (25 females and 25 males). Each infection group was intraperitoneally injected with one of the following bacterial concentrations: 1.0×10³, 1.0×104, 1.0×105, 1.0×106, or 1.0×107 CFU/g body weight. The control group received an equivalent volume of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (Cytiva, MA, USA). Mortality was recorded daily for 14 d. Pathogens were isolated and identified from deceased CSSTs. Each pathogenicity experiment was conducted in triplicate. The median lethal dose (LD50) was calculated using the Reed–Muench method.12

Histopathological Analysis

Three healthy and three naturally diseased CSSTs were dissected after anesthesia. Following death, the liver, spleen, kidney, and intestinal tissues (5 mm³ blocks) were promptly collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 24 h with a 10:1 (v/v) fixative-to-tissue ratio, then rinsed under running tap water for 12 h. Tissues were sequentially dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (50 %, 70 %, 85 %, 95 %, and 100 %) for 2 h per concentration. Dehydrated tissues were cleared in xylene, embedded in paraffin wax (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) at 60°C for 2 h, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness using a rotary microtome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Sections were mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated slides, dried at 42 °C for 24 h, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) following standard protocols: hematoxylin (Sigma, MO, USA) for 8 min and eosin (Sigma, MO, USA) for 3 min. Histological assessment was performed under a light microscope equipped with a DP27 digital camera (20× and 40 × objectives) (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Immune gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from pathologically confirmed hepatic, splenic, and renal tissues of diseased CSSTs using TRIzol® Reagent (Thermo Fisher, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s optimized protocol. Subsequently, 1 μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA according to the instructions of the reverse transcription kit (Yeasen, Shanghai, China). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted using Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (No Rox) (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) with cDNA templates derived from the liver, spleen, and kidney tissues of diseased CSSTs. Gene-specific primers targeting MAP2K6 (XM_007060443.2), MyD88 (XM_007062197.2), and TLR8 (XM_007057266.2) were utilized for amplification in a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher, MA, USA). The primer details are summarized in Table 1. The qRT-PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 30 sec; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 sec and 60 °C for 30 sec, with 18S rRNA as reference gene. Hence, the expression levels of these immune-related genes were analyzed. The fluorescence quantitative data were analyzed using the relative quantification method. First, the Ct value difference between the target gene and the reference gene (ΔCt) was calculated. Next, the ΔCt values were compared between the experimental and control groups to determine ΔΔCt. Finally, the relative expression fold change of the target gene was calculated using the formula 2^(-ΔΔCt), which enabled a comparative assessment of the relative variation in gene expression levels.

Antibiotic sensitivity testing

The antibiotic sensitivity of the pathogen was determined using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method. Bacterial suspensions (0.5 McFarland standard) were spread onto Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) (HopeBio, Qingdao, China) plates and antibiotic discs (Hangwei, Hangzhou, China). The types and concentrations of antibiotics are listed in Table 2. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 20 h. Antimicrobial susceptibility was interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (VET01S) and supplemented by the CLSI guideline (M100-S32), and categorized as sensitive (S), moderately sensitive (M), or resistant (R). Triplicate biological replicates were analyzed to ensure reproducibility.

Results

Clinical signs

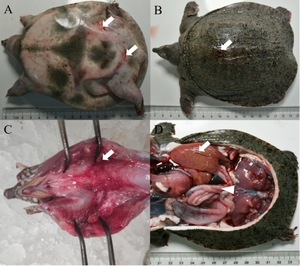

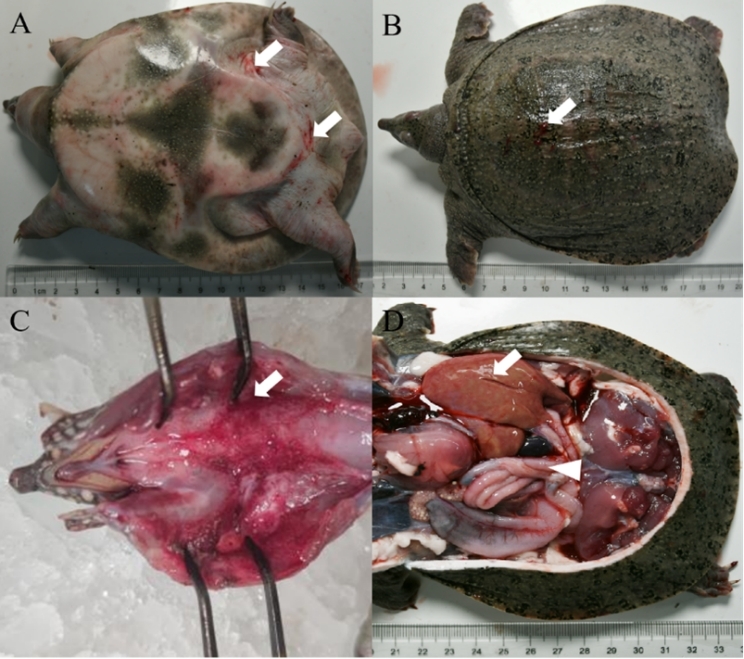

The diseased CSSTs exhibited sluggish responses and limb weakness. Diseased individuals frequently swam alone and displayed abnormal behaviors. Ulcers were observed on the dorsal carapace. In addition, the abdominal shell was thickened, and irregular patches of erythema were visible on the hind-limb epidermis. Upon dissection, the laryngeal mucosa showed erythematous swelling with hemorrhagic foci. The liver was enlarged, fragile, and discolored. Moreover, the spleen was congested, and serosal vasculature congestion was also observed in the intestines (Figure 1).

Morphological Characterization of the Isolated Bacterium

The bacterial strain 211ED12 was isolated from a diseased soft-shelled turtle at an aquaculture facility in Hubei Province and was cultured on a solid TSA (HopeBio, Qingdao, China) plate. Raised, smooth, opaque, round white colonies of 1-2 mm diameter with marginally irregular edges were formed. Gram staining revealed a blue-violet coloration, so the strain 211ED12 was identified as a Gram-positive bacterium. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that the isolated strains exhibited a slightly oval morphology, with a diameter of approximately 1.0 micrometers, and were arranged in a grape-like configuration (Figure 2).

Molecular identification and sequence analysis

The 16S rDNA sequence of strain 2113ED12 demonstrated over 99.96 % similarity with S. epidermidis strains MT585523.1 and MT573029.1 in the GenBank database. Likewise, phylogenetic analysis positioned strain 2113ED12 on the same evolutionary branch as other S. epidermidis strains (Figure 3).

Physiological and biochemical identification

Based on the biochemical reaction profile, strain 2113ED12 was identified as S. epidermidis. The specific test items and corresponding results are presented in Table 3.2. The strain exhibited positive metabolic activity toward various carbohydrates and amino acids, including glucose, maltose, sucrose, L-alanine, and N-acetylglucosamine. Additionally, the strain exhibited positive tolerance to 1-8 % NaCl concentrations and was sensitive to antibiotics such as lincomycin and nalidixic acid. Conversely, it displayed negative metabolic reactions towards polyol compounds like mannitol, arabitol, and sorbitol, while demonstrating resistance to antibiotics vancomycin and rifamycin SV (Table 3).

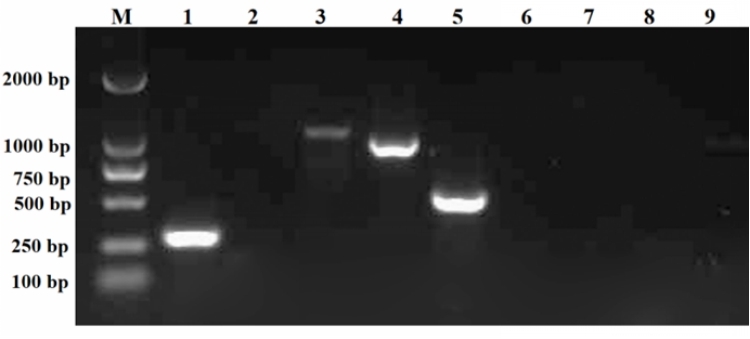

Virulence genes

The PCR amplification results revealed that strain 2113ED12 harbored numerous toxin genes, including icaA, clfA, mecA, and bhp (Figure 4). In contrast, the 2113ED12 strain lacked the icaD, Nuc, lukS, expB, and IS256 genes.

Pathogenicity testing

Infection experiments were conducted on healthy CSSTs to validate the pathogenicity of the isolated strain 2113ED12. The results showed an 8% survival rate in the 2113ED12-infected group (1.0×108 CFU/g weight), as displayed in Figure 5. The LD50 of the isolated strain was 8.99×10³ CFU/g weight. The infected CSSTs exhibited symptoms similar to natural infections, including abdominal carapace hemorrhage and erythematous swelling of the laryngeal mucosa with hemorrhagic foci. In contrast, no clinical symptoms or mortality were observed in the PBS control group. At the end of the experiment, S. epidermidis was re-isolated from the artificially infected CSSTs. Collectively, these results confirmed that strain 2113ED12 is the causative pathogen of the diseased CSSTs (Figure 5).

Histopathological observation

The infected CSSTs exhibited significant pathological changes in several tissues compared to healthy individuals (Figure 6). Histological analysis revealed hepatocyte vacuolization, degeneration, and necrosis. Marginalization of nuclear material and enlargement of hepatic sinusoids were observed, accompanied by extensive erythrocyte congestion (Figure 6a). The spleen displayed vacuolization lesions, widespread necrosis of splenic cells, and marginalization of nuclear material (Figure 6b). In the kidneys, tubular epithelial cells were swollen and necrotic, accompanied by extensive infiltration of inflammatory cells (Figure 6c). The intestines displayed mucosal epithelial cells, numerous mucosal fragments sloughing into the intestinal lumen, and a disordered arrangement of myocytes in the muscle layer. Concurrent villus atrophy was histologically confirmed (Figure 6d). The serosal vasculature was also congested in the diseased intestines. No pathological symptoms were identified in the internal tissues of healthy CSSTs.

Relative Expression Levels of Related Immune Genes

This study compared the relative expression levels of immune genes (MAP2K6, MyD88, and TLR8) across different tissues (liver, spleen, and kidney) in CSSTs between the healthy and infected groups (Figure 7). The results indicated significant upregulation of gene expression in all tissues of the infected group. In the liver, spleen, and kidney tissues, the expression levels of MyD88, MAP2K6, and TLR8 genes were significantly increased. Specifically, the expression of MyD88, TLR8, and MAP2K6 were upregulated by 2-7-fold in multiple tissues (P < 0.01), with the highest levels detected in the kidney and liver (P < 0.01).

Antibiotic Sensitivity

Strain 2113ED12 was sensitive to multiple antimicrobial agents, including amikacin, doxycycline, florfenicol, neomycin, enrofloxacin, and cephalothin. However, the strain showed resistance against sulfamethoxazole, compound sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin, as displayed in Table 2.

Discussion

S. epidermidis is a Gram-positive coccus commonly identified on the skin and mucous membranes, typically existing as a commensal organism.14 In clinical microbiology, accurately distinguishing S. epidermidis from Staphylococcus aureus is essential due to their morphological similarities. Specific biochemical characteristics can be analyzed to facilitate their differentiation.15 S. epidermidis typically forms white, raised, cohesive colonies of approximately 1–2 mm in diameter on tryptic soy agar (TSA) and does not ferment mannitol, producing no color change on mannitol salt agar (MSA).16 Additionally, S. epidermidis lacks gelatinase activity and cannot hydrolyze gelatin. In contrast, S. aureus often produces golden-yellow colonies on TSA and ferments mannitol, thereby producing a yellow color on MSA due to acid production. Moreover, it possesses gelatinase activity, enabling gelatin hydrolysis. These biochemical distinctions play a crucial role in the accurate identification and appropriate clinical management of infections caused by these organisms.17 This bacterium may be pathogenic in immunocompromised individuals or those with skin injuries, potentially resulting in severe infections.18 S. epidermidis has been reported to cause pathological conditions such as dermatitis and septicemia in multiple species and is particularly prevalent in mammals.19 After infecting CSSTs, strain 2113ED12 elicited symptoms such as skin ulcers and septicemia, further highlighting the pathogenicity of S. epidermidis in reptiles.

Histopathological examination represents an integral approach in veterinary clinical pathology research.20 This technique has been widely employed to assess the impact of pathogenic bacterial infections on the host.21 S. epidermidis infections can elicit severe organ damage in species such as humans, pigs, and cattle, particularly affecting the liver and spleen.22–27 For instance, in human and cattle infection models, severe inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in the liver after infection. In pigs, spleen infections manifested as a reduction in lymphocyte count.22–27 In this study, CSSTs infected with S. epidermidis developed severe liver and spleen damage. Specifically, extensive inflammatory infiltration and tissue damage were observed in these tissues, similar to changes observed in infection models of mammals such as humans and cattle. Furthermore, histopathological observations confirmed that the bacterium affected various tissues. Lesions in the spleen and liver were particularly pronounced, indicating that these organs have a higher sensitivity to infection, consistent with the pathological characteristics observed in other species and further emphasizing the high pathogenicity of strain 2113ED12 in CSSTs.

Additionally, the strain 2113ED12 was found to harbor four virulence genes, including icaA, clfA, mecA, and bhp, which are crucial factors in the pathogenesis of infections.19 While five other virulence-associated genes, namely icaD, nuc, lukS, expB, and IS256, were not detected. Similarly, Zhou et al. further investigated 83 S. epidermidis strains isolated from patients with periprosthetic joint infections and reported detection rates of 56.0% for icaA, 45.1% for bhp, and 68.9% for mecA, which are largely consistent with the findings of the current study.19 However, with regard to the IS256 gene, its detection rate was 20.73% in the former study and 100% in the latter, whereas it was not detected in strain 2113ED12.21,28 These differences may be attributed to regional variations and differences among isolates from different infected animals.

Antibiotic sensitivity testing should be conducted to facilitate the treatment of bacterial disease.29,30 In the present study, strain 2113ED12 was found to be sensitive to multiple antimicrobial agents, including gentamicin, doxycycline, florfenicol, neomycin, enrofloxacin, and cefotaxime. However, the strain showed resistance against sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, compound neomycin, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin, providing a scientific basis for clinical treatment. Similar results have been reported in previous studies. For example, S. epidermidis isolated from Tilapia also demonstrated significant resistance to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin.31 In infection studies in pigs, S. epidermidis exhibited sensitivity to doxycycline.32 These results are consistent with the antibiotic sensitivity tests in this study, indicating that the rational use of antibiotics remains effective in controlling S. epidermidis infections. Based on the laboratory-based antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) results, the aquaculture facility implemented a targeted therapeutic regimen utilizing antibiotics to which the pathogen exhibited high susceptibility. Combined with systematic disinfection protocols, this strategy effectively contained a large-scale outbreak of S. epidermidis in CSSTs, achieving a significant reduction in both morbidity and mortality rates. However, variations in antibiotic sensitivity have been identified in S. epidermidis isolated from different regions and species. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed that the infecting Staphylococcus epidermidis strain exhibits resistance to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim and ciprofloxacin. Consequently, extensive use of these antibiotics in treatment should be strictly avoided. Indiscriminate overuse may accelerate the selection of resistant bacterial strains, which can potentially transmit to humans through the food chain (e.g., consumption of aquaculture products) or environmental media (e.g., water bodies, sediment). Such transmission poses a heightened risk of clinical treatment failures, exemplified by increased therapeutic challenges in managing human urinary tract infections and respiratory tract infections.33,34 Therefore, the selection of antibiotics for the treatment of bacterial diseases should be guided by sensitivity testing, prioritizing antibiotics approved by local authorities.

The immune system serves as a critical defense mechanism against diseases.35 Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a pivotal role in recognizing pathogens and initiating innate immune responses.32,36 Bacterial and viral infections have been shown to upregulate the expression of TLR8 and MyD88 genes in various animal models. Notably, MAP2K6, a component of the MAPK signaling pathway, plays a central role in mediating stress, inflammatory, and immune responses.37 In humans and cattle, S. epidermidis infection results in the upregulation of MyD88 and TLR8 genes, indicating activation of the immune system. Specifically, a sixfold increase in MyD88 expression was observed 48 h post-infection in humans, while TLR8 expression was quadrupled in cattle.38 In the present study, infection with strain 2113ED12 led to a significant upregulation of MAP2K6, MyD88, and TLR8 genes in the liver and kidneys of CSSTs, especially the MyD88 gene, which was upregulated by over fivefold. Consistent with host immune response characteristics observed in previous studies, these results suggest that CSSTs respond to S. epidermidis infection by activating multiple immune pathways. The upregulation of these immune genes is closely related to the host’s stress response to bacterial infection, particularly the pro-inflammatory responses mediated by MyD88 and TLR8.38,39 This enhances the host’s defensive capabilities. Compared to other species, CSSTs exhibit more pronounced inflammatory responses post-infection. This may be attributed to their inherent immune mechanisms and the virulence characteristics of S. epidermidis.38,39

Collectively, the results of this study imply that S. epidermidis induces a range of typical pathological symptoms in CSSTs, including abdominal inflammation and dorsal ulcers. Infected CSSTs exhibited significant damage to the liver, spleen, kidneys, and intestines. Concurrently, the expression of immune-related genes TLR8, MyD88, and MAP2K6 were upregulated to varying degrees. More importantly, antibiotic sensitivity testing revealed that strain 2113ED12 was sensitive to gentamicin, doxycycline, florfenicol, neomycin, enrofloxacin, and cephalothin. Overall, the results of this study provide a scientific reference for elucidating the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of S. epidermidis-induced diseases in CSSTs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (NO. YFI20240603), The Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of Hubei Province (2023DJC102), Key Lab of Freshwater Biodiversity Conservation Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China Open Project (No. LFBC1116) and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (No. 2023TD46). Thanks to Hubei Hongwang Ecological Agricultural Technology Co., Ltd. for providing healthy laboratory animals.

Authors’ Contribution

Writing – original draft: Chunjie Zhang; Conceptualization: Chunjie Zhang, Wei Liu, Mingyang Xue; Methodology: Chunjie Zhang,Wei Liu; Data curation: Chunjie Zhang, Wei Liu; Investigation: Yan Meng, Tong Zhou; Writing – review and editing: Yan Meng, Xiaodan Liu, Yong Zhou; Validation: Mingyang Xue, Nan Jiang; Formal analysis: Nan Jiang; Resources: Mingyang Xue, Xiaodan Liu, Yong Zhou; Supervision: Tong Zhou; Visualization: Zidong Xiao; Project administration: Hongyang Song, Mengmeng Chen; Funding acquisition: Xiaodan Liu, Yong Zhou.

Competing of Interest – COPE

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical Conduct Approval – IACUC

In this study, all experimental procedures were conducted according to guidelines of the appropriate Animal Experimental Ethical Inspection of Laboratory Animal Centre, Yangtze River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (ID Number: YFI 2023-zhouyong-0516), date 2023-05-16.

Informed Consent Statement

All authors and institutions have confirmed this manuscript for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

_liver_of_a_healthy_chines.png)

_liver_of_a_healthy_chines.png)