Introduction

Litopenaeus vannamei is one of the most economically valuable shrimps in the global aquaculture industry. It is also the most widely produced and sought-after shrimp species in China. In 2023, its mariculture production reached 1,429,800 tonnes, accounting for 80.94% of the national shrimp mariculture production.1 The fast expansion of the shrimp-intensive aquaculture industry has raised aquaculture density and feed intake, ultimately increasing the production value of farmed animals and the utilization of farm space.2 However, the decomposed and metabolized NH4+-N, NO2--N, and other toxic substances, such as bait, excreta, and limbs deposited in the culture water body, lead to an increasing deterioration of the ecological environment of the culture water and negatively affect the growth of the culture objects.3 The drawbacks of the conventional shrimp aquaculture model gradually appeared in this context. First, the deterioration of water quality caused by high-density aquaculture not only affects the growth rate of shrimp but also may engender disease outbreaks, increasing the risk of aquaculture. Second, frequent water changes in aquaculture are attributed to the high dependence on water resources, and the country’s water conservation and environmental protection requirements are opposite to these requirements. In addition, the excessive use of antibiotics has also created food safety risks. As the country’s food safety and environmental protection criteria continue to improve, traditional farming makes it challenging to meet sustainable development provisions.4 To resolve the shrimp aquaculture industry facing multiple conflicts, such as aquaculture safety, food safety, and ecological safety, the development of green, environmentally friendly alternatives to antibiotics and exploring novel breeding modes are gradually becoming a focus of attention and one of the critical research direction of aquaculture.5 Therefore, it is crucial to investigate water-saving and emission-reduction shrimp aquaculture technology to enable the sustainable development of shrimp aquaculture in China.6

As a fresh type of aquaculture model, zero water discharge (ZWD) has received widespread attention in recent years. It is currently divided into two types: in situ water treatment and ectopic water treatment. ZWD is commonly used in factory water recirculation aquaculture systems,7 which offers the advantages of high yield and strong controllability.8 However, its equipment investment and operating costs are high, requiring stringent specialization of the relevant technology and personnel. Therefore, this model has a limited scope of application and has not been widely endorsed. In contrast, in situ water treatment applies the principle of bioflocculation for water quality control, which is a more economical and practical way of zero water exchange culture. Biofloc technology uses heterotrophic bacteria and plankton in the water column to develop a stable microbial community by adding carbon sources and adjusting the carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio, thus realizing the self-purification of water quality.9 Adding different carbon sources10,11 or adjusting different C/N ratios to construct bioflocs under zero-water exchange conditions affects the water quality and growth, body composition, digestive enzymes and immunity, and antioxidants of cultured subjects.12–14 These research results provide essential theoretical support and practical guidance for the further optimization of zero water exchange aquaculture technology.

As a new type of feed additive and water quality improver, sodium humate has gradually captured attention for its application in aquaculture in recent years. Sodium humate is the sodium salt of humic acid and is produced from peat, lignite and weathered coal, which are widely distributed in nature.15 Sodium humate has been used as a feed additive, substantially increasing feed utilization and enhancing the quality of meat, eggs, and dairy products.16–18 As a natural organic substance, sodium humate is rich in carbon sources. It provides nutritional support for heterotrophic bacteria in the culture water, thus promoting the growth and metabolic activities of microbial communities. Some studies have demonstrated that sodium humate can reduce water quality physicochemical indicators such as ammonia nitrogen, nitrite and hardness in aquaculture water.19 However, few studies have been reported on the impact of sodium humate on shrimp aquaculture efficiency.

Based on these advantages, this study applied sodium humate to the zero-water exchange culture of L. vannamei to investigate the effects of different concentrations of sodium humate on the growth, digestion, non-specific immunity and microbial environment of L. vannamei, provide fundamental data for the promotion of the ecological environment of L. vannamei, and develop healthy aquaculture technology under the condition of zero-water exchange.

Materials and Methods

Experimental materials and feeding management

The experiments were performed in Hainan Zhongzheng Aquatic Technology Co., Ltd., Dongfang City, Hainan Province, over 54 days. Sodium humate was produced in Wuhai Hongli Chemical Plant, Inner Mongolia (humic acid purity≥90%). It was crushed, passed through a 200-mesh sieve, and dissolved in water. L. vannamei (specific pathogen-free,SPF) seedlings were from Hainan Zhongzheng Aquatic Technology Co., Ltd. They were fed with artificial compound feed in an indoor cement tank (Aohua Group Joint Stock Co., crude protein >42.0%) until the body length of the prawns was 2.43 ± 0.04 cm and the body mass was 0.28 ± 0.01 g. In the experiment, active, healthy shrimp with no injuries, intact limbs, and uniform size were selected.

The experiment was conducted in a 500 L black plastic bucket. The aquaculture water body was 400 L, and the aquaculture density was 300 tails·m–3. The water temperature during the experimental period was 26–30℃, and the salinity was 32–34‰. The experimental seawater was used after precipitation, sand filtration, and chlorine disinfection. Three gas stones were placed in each experimental bucket, and the water body was continuously and evenly aerated. During the experiment, artificial compound feed was fed four times daily at 08:00, 12:00, 16:00 and 20:00. The feeding amount was 5–10% of the shrimp’s body mass. Adjustments were made according to the shrimp’s feeding and growth situations. No water was changed during the experiment, but the evaporation loss was supplemented with dechlorinated fresh water.

Experimental design

A total of five groups were established in the experiment, containing one control group and four additive groups, wherein the control group did not add any substance. In contrast, the additive groups were labelled as SH3, SH6, SH9 and SH12, and sodium humate was added to the water column to reach the concentrations of 3 mg/L, 6 mg/L, 9 mg/L and 12 mg/L, respectively. Three parallels were created in each group, and the sodium humate was replenished once every ten days to maintain the stability of the target concentration in the experimental water.

Measurement of shrimp’s growth performance

In total, 30 prawns were randomly selected from each group before the start of the experiment and the body length of the prawns was measured. After draining the water with filter paper, the body mass was measured using an electronic balance. At the end of the aquaculture experiment, the number of prawns in each parallel was recorded, and the body length and mass were determined. Next, the survival rate (SR), the weight gain rate (WGR), the feed coefficient (FC) and the specific growth rate (SGR) of the prawns were calculated:

SR (survival rate, %) = Nt / N0 × 100;

WGR (weight gain rate, %) = (Wf–Wi)/W;

FC (feed coefficient) = Wz /( Wt–W0);

SGR (specific growth rate, %/d) = [ (lnWf–lnWi)/T] × 100。

where N0 and Nt are the initial and final numbers of shrimp, respectively. W0 and Wt are the total weight (g) of the shrimp at the beginning and the end of the experiment, respectively. Wz is the total amount of feed invested during the experiment (g). Wf and Wi are the average weights at the end and the beginning of the experiment for each repeated experiment, respectively. T is the number of experiment days (d).

Determination of water quality indicators and bacterial count

The concentrations of ammonia nitrogen (NH4+-N), nitrite nitrogen (NO2–-N), nitrate nitrogen (NO3–-N), total alkalinity, and phosphate concentration in the water were determined every three days during the test period, with reference to GB 17378.4-2007 ‘Marine Monitoring Specifications Part 4: Seawater Analysis’. Ammonia nitrogen was determined using indophenol blue spectrophotometry, nitrite nitrogen using naphthalene ethylenediamine spectrophotometry, nitrate nitrogen by the zinc-cadmium reduction method, and phosphate by ammonium molybdate spectrophotometry. The pH, water temperature, dissolved oxygen and salinity were measured daily. Water temperature and salinity were measured using a written test salinity meter (AZ8371, Hengxin, Taiwan). Dissolved oxygen was measured using a portable dissolved oxygen analyzer (JPB-607A). The pH was determined using a pH meter (SX-610, Shanghai Sanxin Instrument Factory). The bioflocculent volume (BFV), heterotrophic bacteria and Vibrio numbers were measured weekly, as described below.

Bioflocculent volume (BFV): 1 L of water sample was deposited in an Inhofe conical tube, and the sedimentation volume was recorded after 30 min.

Number of heterotrophic bacteria: Each water sample measuring 50 mL was placed in a sterilized centrifuge tube. After diluting the water sample, 0.1 mL was kept on a 2216E agar plate (Qingdao Haibo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for counting plate colonies. The heterotrophic bacteria were counted after being cultured in a 30°C constant-temperature incubator for 24 hours.

Number of Vibrio: Each 50 mL water sample was kept in a sterilized centrifuge tube. A 0.1 mL aliquot was diluted and coated on a TCBS agar plate (Beijing Luqiao Technology Joint Stock Co.). Then, it was cultured in a 30°C constant-temperature incubator for 24 hours. The Vibrio were then counted.

Determination of digestive enzyme and immunoenzyme activity

Following the experiment, 15 prawns were randomly selected from each breeding bucket and dissected with sterilized forceps and scissors. The hepatopancreas and whole intestines were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then cryopreserved at –80°C. The hepatopancreas was used to determine the activity of non-specific immunoenzymes, and the entire intestine was used to assess the activity of digestive enzymes. Intestinal amylase (amylase), lipase, trypsin, hepatopancreatic superoxide dismutase (SOD), lysozyme, phenol oxidase (PO) and catalase (CAT) were determined with the relevant kits produced by Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Bioengineering.

Collection of microbial samples

After the experiment, 1 L of water was taken from each experimental bucket, and 100 mL aliquots were filtered through separate 0.45 μm filter membranes. The filter membranes were collected in sterile centrifuge tubes measuring 50 mL and quickly stored at –80°C to determine aquatic flora.

DNA extraction and library construction and sequencing

First, the microbiota DNA was extracted and quality assayed using the MagPure Stool DNA KF kit B (Magen, China) and the PowerWater DNA isolation kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. DNA was extracted from 20 samples (including gut and culture water samples) to extract the microbial community DNA. Next, the DNA’s quality was assessed by running aliquots on a 1% agarose gel to ensure that the extracted DNA was suitable for subsequent experimental analysis.

High-throughput sequencing was performed by the Wuhan Branch of UW Genome Science and Technology Service Co. After extracting the total DNA of the samples, the primers were designed according to the conserved region of the 16S rRNA gene and sequencing connectors were added at the end of the primers. PCR amplification of the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using primer pairs 341F (5’ACTCCTACGGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 806R (5’GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’). The amplification products were purified, quantified, and homogenized to create sequencing libraries. The constructed libraries were first subjected to quality testing to ensure that they were qualified. Next, high-throughput sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq platform. The raw image data files obtained from sequencing were converted into Sequenced Reads by Base Calling analysis. Next, the findings were stored in FASTQ (fq) file format, which contains the sequence information of the ordered sequences and their corresponding sequencing quality information. The first step was quality filtering, using Trimmomatic v0.33 software to filter the Raw Reads obtained from sequencing, Then, cutadapt 1.9.1 software was used to identify and remove the primer sequences to obtain Clean Reads without primer sequences. 2020.6 in the dada2 method for denoising, bipartite sequence splicing and removing chimeric sequences to determine the final valid data (non-chimeric reads).

All the sequencing results reported in this paper are stored in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Short Read Archive (SRA) and are stored under accession number PRJNA1202863 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra).

Data processing

Excel 2016 was used to organise and summarise the experimental data. SPSS 26 was used for single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the experimental data, with P<0.05 indicating a significant difference. Multiple comparisons were performed using the Duncan test when the difference was substantial.

Results

Growth performance of shrimp

Table 1 shows the growth performance parameters of shrimp Penaeus vannamei after 54 days of culture experiments with different concentrations of sodium humate. The SRs of shrimp ranged from 78.1% to 87.2%, with the survival rate of shrimp in the spiked group SH3 (87.2%) being significantly higher than that of the control group (78.1%) (p<0.05) and that of shrimp in the rest of the experimental groups being higher than that of the control group. The final body weight (FW), WGR and SGR were significantly (p<0.05) higher in all the additive groups than in the control group. FC of shrimp ranged from 1.19 to 2.28 and were significantly lower in all the additive groups than in the control group (p<0.05). The above findings indicated that adding sodium humate could substantially promote the growth performance of L. vannamei and lower the FC while increasing the SR, showcasing the best effect in the addition group SH3.

Changes in water quality indicators in shrimp aquaculture

Table 2 presents the variations of water quality parameters during the zero-water exchange aquaculture of L. vannamei. During the 54 days of the shrimp culture experiment, the average water temperature of the culture water body was around 26℃, salinity: 30.49–31.20, pH: 7.61–7.68, dissolved oxygen (DO): 6.61-6.63 mg/L, total alkalinity: 89.39–92.81 mg/L, biofloc volume (BFV): 1.06–1.86 mL/L, phosphate concentration: 1.66–1.83 mg/L, NO2–-N concentration: 3.56–9.23 mg/L, NO3–-N concentration: 15.72–28.31 mg/L, and NH4+-N concentration: 0.37–0.43 mg/L. Supplementing different concentrations of sodium humate exhibited no considerable effect on the water temperature, salinity, pH, DO, total alkalinity, BFV, phosphate concentration and NH4+-N concentration of the cultured water. Concentrations were not significantly affected. The lowest NO2–-N concentration was revealed in the spiked group SH12 and was significantly lower (p<0.05) than the spiked groups SH6 and SH9. The lowest NO3–-N concentration was observed in the addition group SH12 and was significantly lower than the addition group SH9 (p<0.05).

During the experimental period, the changes of NO2–-N, NO3–-N and NH4+-N concentrations, as well as the biofloc group volume in the zero water exchange culture water body of L. vannamei are highlighted in Fig.1, where the NO2–-N, NO3–-N and NH4+-N concentrations as a whole revealed an overall trend of increasing and then decreasing. The biofloc group volume displayed a trend of increasing all the time. The NH4+-N concentration of each group reached the highest concentration on day 9, sharply reduced on day 15 and remained low thereafter (Figure 1a). The NO2–-N concentrations of all groups displayed the same trend in the first 24 days. Next, SH3 and SH12 of the additive group started to decrease continuously on the 27th day, and SH6 and SH9 of the control and additive groups started to decline sharply on the 36th day (Figure 1b). The NO3–-N concentrations of each group demonstrated an increasing trend throughout the first 27 days without significant differences, after which SH3 and SH12 began to decline in the additive group. Next, the control group reached the highest concentration and started to reduce on the 33rd day. The additive group SH6 and SH9 reached the highest concentration and began to lower significantly on the 45th day (Figure 1c). There was no significant difference in the biofloc volume of each group in the first seven days. The SH12 of the addition group was significantly higher than that of the control group after the seventh day. The SH9 and SH12 of the addition group were considerably higher than that of the control group at the 49th day (p<0.05) (Figure 1d). The above conclusions suggested that adding sodium humate could enable the growth of biofloc volume in aquaculture water and reduce the accumulation of NO2–-N and NO3–-N to a certain extent, and the best effect was observed in the addition group SH12.

Activity of digestive enzymes in the intestinal tract of L. vannamei

At the end of the experiment, the amylase, lipase and trypsin activities in the intestinal tract of L. vannamei were determined (Figure 2). Among them, there was no significant difference for amylase and lipase. However, trypsin exhibited a significant difference (p<0.05), and the SH9 group showed the highest levels of lipase and trypsin. The above results indicated that adding 9 mg/L of sodium humate could increase the lipase and trypsin activities in the intestinal tract of L. vannamei.

Hepatopancreas immunoenzyme activity in L. vannamei

Figure 3 displays the findings of superoxide dismutase (SOD), PO, catalase (CAT) and lysozyme activities in the hepatopancreas of L. vannamei at the end of the experiment. There were significant differences (p<0.05) in superoxide dismutase, phenoloxidase, catalase and lysozyme in all groups, with a substantial increase in superoxide dismutase and lysozyme in the SH9 group, phenoloxidase in the SH12 group and catalase in the SH6 group. The above outcomes indicated that the addition of a certain concentration of sodium humate could considerably escalate the activities of SOD, PO, CAT and lysozyme in the hepatopancreas of L. vannamei.

Heterotrophic bacteria and vibrio populations in culture waters

Table 3 shows the heterotrophic bacterial counts and Vibrio counts in zero water exchange culture water of L. vannamei during the experimental culture period with different concentrations of sodium humate. During the culture period, the number of heterotrophic bacteria in the experimental group was higher than that of the control group. In contrast, the number of Vibrio spp. was lower than that of the control group. The control group had the lowest heterotrophic bacterial count of 14.48 ± 21.25 CFU/mL. The highest was 27.99 ± 34.86 CFU/mL in SH12 in the spiked group. The heterotrophic bacterial counts in each spiked group increased with sodium humate concentration. The highest number of Vibrio spp. in the control group was 388 ± 242 CFU/mL, and the lowest number of Vibrio spp. in the control group was 246 ± 214 CFU/mL, the highest number of Vibrio flavus in the control group was 190 ± 186 CFU/mL, and the lowest number of Vibrio spp. in the control group was 116 ± 185 CFU/mL. The highest number of Vibrio greenus in the control group was 198 ± 166 CFU/mL, and the lowest number of Vibrio spp. in the control group was 115 ± 122 CFU/mL. The above conclusions revealed that the addition of sodium humate could increase the number of heterotrophic bacteria in the zero-water exchange culture water of L. vannamei and decrease the number of Vibrio to a certain extent, with the lowest number of Vibrio in the addition group SH3.

Effects of different concentrations of sodium humate on the abundance and diversity of bacterial communities in zero water exchange culture waters of L. vannamei

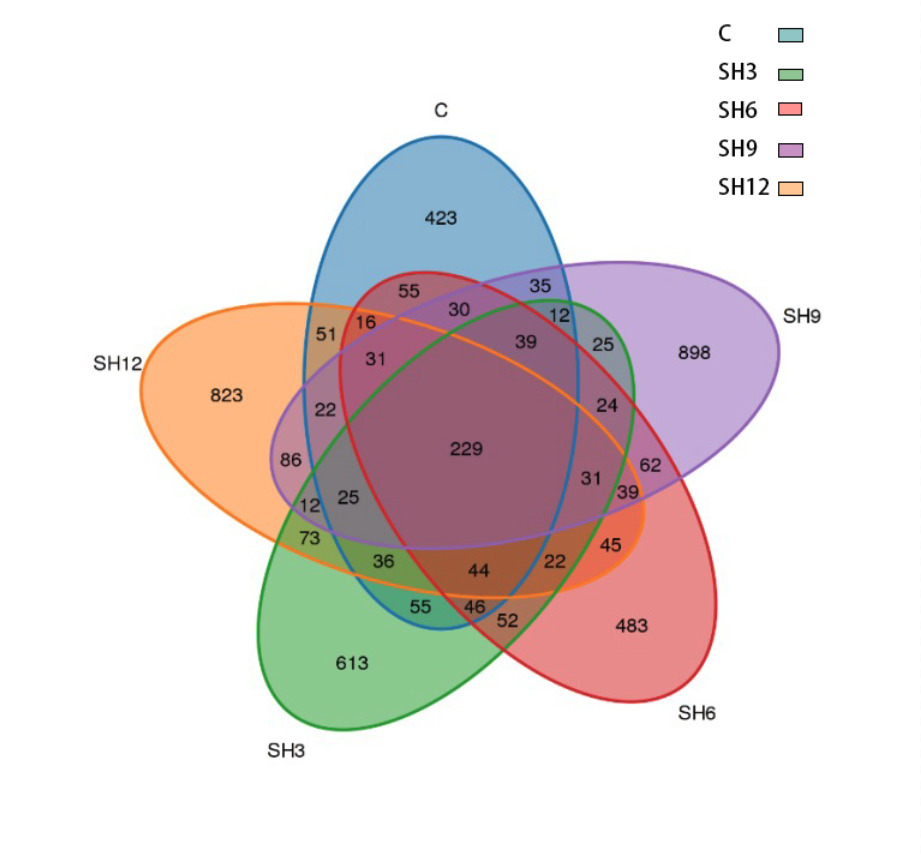

Wayne’s plot of the number of OTUs in the flora of shrimp culture water in L. vannamei demonstrated (Figure 4) that the number of OTUs common to each group in the culture water was 229, the number of OTUs specific to the control group was the lowest at 423, and the number of OTUs specific to the SH9 addition group was the highest at 898. The number of OTUs specific to each addition group was substantially higher than that of the control group, indicating that adding sodium humate increased the number of microbial communities in the water of shrimp culture in L. vannamei’s microbial community in the aquaculture water body of L. vannamei. Wayne’s plot of the number of OTUs in the cultured water flora of L. vannamei revealed (Figure 4) that the number of OTUs common to all groups in the cultured water was 229, and the lowest number of OTUs specific to the control group was 423. The highest number of OTUs specific to the SH9 of the additive group was 898. The number of OTUs specific to each addition group was considerably higher than that of the control group, indicating that adding sodium humate increased the number of microbial communities in the water column of shrimp culture in L. vannamei.

Table 4 displays the effects of different concentrations of sodium humate on the Alpha diversity index of water column flora in the zero-water exchange culture of L. vannamei. The Coverage index was greater than 0.99 in all groups, indicating that the sequencing depth had effectively covered the sample flora. There was no considerable difference in Chao1 index, Ace index, Shannon index and Simpson index in the additive group compared to control group C. The Chao1 index and Ace index of the experimental group were greater than that of the control group C, and SH3 was significantly higher than that of the control group. The Shannon index of SH12 was 7.35 ± 0.91, which was considerably higher than that of the control group (7.04 ± 0.14). The above findings indicate that adding sodium humate to the culture water of L. vannamei can optimize the richness of the microbial community in culture water to a certain extent.

PCA analysis of water flora in zero water exchange aquaculture of L. vannamei

Figure 5 shows the PCA analysis of the water column flora of L. vannamei zero water exchange aquaculture. PCA1 is 50.16%, and PCA2 is 13.76%. Combined with this figure, it can be observed that the water column flora of L. vannamei can be well clustered between the samples of the same group, and the different groups can be clearly distinguished from each other. The cohort samples of SH3 were more concentrated among each other and could be clearly distinguished from the control group at a closer distance. The cohort samples of SH6 and SH9 were more dispersed among each other and were farther away from the control group. The above results indicate that adding sodium humate can considerably alter the flora composition of the zero-water exchange culture water body of L. vannamei.

Effects of different concentrations of sodium humate on the structural composition of the bacterial flora of L. vannamei aquaculture water bodies

At the phylum level, there were 36 phyla in the water column flora of L. vannamei zero-water exchange culture in different concentrations of sodium humate experiments, which were mainly composed of the phyla of Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Patescibacteria, accounting for 90% of the cultured water flora in each group. The relative abundance of Proteobacteria was highest in each group, followed by Bacteroidota (Figure 6). Among them, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria phylum was the lowest in the addition group SH9 (41.43%), which was significantly lower than that in the control group C (31.26%) and other addition groups (p<0.05), and the overall tendency was to decrease firstly and then increase; in the Bacteroidota phylum the relative abundance in SH9 was significantly higher than that in the control group C and other addition groups, and the overall tendency was to increase firstly and then decrease. The relative abundance of Actinobacteriota phylum in addition group SH6 was significantly higher than that in control group C and other addition groups (p<0.05), but the relative abundance of Chloroflexi phylum in control group C was significantly higher than that in each addition group (p<0.05). The relative abundance of the thick-walled phylum of SH9 (5.21%) and SH12 (4.45%) in the addition groups was similar but significantly higher (p<0.05) than that of control C (0.11%) and the other addition groups.

At the genus level, a total of 795 bacterial genera were detected in each experimental group. Of these, the “Others” group (including low abundance and unclassified genera) accounted for the highest proportion. Known genera with high relative abundance mainly included Marivita, Marinicella, Polaribacter and Woeseia (Figure 7). Of particular note, the relative abundance of Polaribacter in the SH3 group was significantly higher (p<0.05) than that of control group C and the other additive groups. Polaribacter belongs to the Flavobacteriaceae family, which plays an important role in the degradation of high molecular weight dissolved organic matter such as proteins and polysaccharides, and is involved in nitrogen recombination. Polaribacter belongs to Flavobacteriaceae and plays an important role in the degradation of high molecular weight dissolved organic matter (such as proteins and polysaccharides) and participates in nitrogen remineralization. Its significant enrichment in the SH3 group suggests that low doses of sodium humate may promote the decomposition of organic matter and nitrogen cycling process. The relative abundance of Saprospiraceae (Spirochaetaceae) was increased in all the sodium humate-added groups compared to the control group. Bacteria of this family are extensively involved in the degradation of complex organic matter, such as chitin and cellulose, and may play a key role in nutrient cycling at the substrate-water interface. In addition, the relative abundance of Marinicella was higher (p<0.05) in each of the added groups than in the control group. Marinicella belongs to the Roseobacter group, which is commonly associated with aerobic and anaerobic photosynthesis, sulphur cycling, and organic carbon utilization. The increase in the treatment group may reflect the enhanced availability of organic carbon or sulfur compounds in the water column after the addition of sodium humate, thus promoting the growth of this taxon.

Discussion

Effect of sodium humate on growth performance and enzyme activities of L. vannamei

Studies on livestock and poultry animals, such as pigs, sheep and rats, have discovered that sodium humate exerts multiple positive effects on animals. Sodium humate can profoundly enhance the immune indicators of pigs and boost the organism’s immunity, thus improving the growth performance of pigs.20 In addition, other studies have confirmed the positive effects of sodium humate on animal immunity. For example, some scholars have found that sodium humate could alleviate ETEC K88-induced intestinal dysfunction by restoring intestinal barrier integrity and modulating intestinal microbiota and metabolites in mice.21 Some scholars have also found that under the combined effect of sodium humate and glutamine, the intestinal microbiota ecology and metabolic profile of weaned young heifers changed, thereby reducing the incidence of diarrhea in weaned young heifers.22 Research has found that adding about 0.35% sodium humate and 0.02% probiotics to broiler feed can improve intestinal growth performance, carcass characteristics, and morphological features.23 Moreover, some scholars have found that adding sodium fulvate to the diet not only increases the protein content of egg whites but also improves the immunity of laying hens.24 Some scholars’ research found that adding sodium fulvate to broiler feed can promote growth efficiency and have a positive impact on the production performance and economic benefits of broilers.18 Some researchers have also found that sodium humate can promote the immune function of broilers, indicating that sodium humate can alleviate intestinal barrier damage caused by Salmonella typhimurium infection in broilers.25 Meanwhile, studies have shown that adding sodium humate at 0.28% to 0.37% to the feed of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) helps improve their growth and health.26 However, research on the effects of sodium humate on aquatic animals is very limited, especially with regard to shrimp. This is because the shrimp immune system is “non-specific, no memory, fast response but limited capacity” of the innate immune system, and the vertebrate “specificity, memory, fine regulation” of the adaptive immune system is completely different. This is also why the shrimp culture is prone to frequent occurrence of disease, making it difficult to prevent and control through vaccines the root cause. Studies have shown that adding sodium humate to the diet of Macrobrachium nipponensis significantly improves their growth.27 We found that sodium humate and probiotics significantly affect the growth performance and enzyme activity of L. vannamei in high-density zero water exchange systems, which can effectively improve the SR and enzyme activity of L. vannamei.19 This study’s results indicated that adding sodium humate significantly promoted growth performance, increased the SR of L. vannamei, enhanced the activity of non-specific enzymes and decreased the FC. This finding is consistent with the findings of other scholars, especially in the field of aquatic animals. These studies suggest that sodium humate positively impacts aquatic animals’ growth, especially in enhancing their immunity and improving digestion.

Effect of sodium humate on aquaculture waters

In aquaculture, nitrite nitrogen and ammonia nitrogen are the two main forms of inorganic nitrogen, which can be converted to nitrate by autotrophic bacteria through nitrification, taken up by heterotrophic bacteria, and converted to bacterial proteins. Many studies have shown that the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio is essential for bacterial growth and colonization. Adding an external carbon source can significantly promote the colonization of heterotrophic bacteria for converting inorganic nitrogen into bacterial proteins.28 Supplementing carbon from external sources can substantially reduce ammonia, nitrogen and nitrite in water bodies.29 External carbon sources can significantly increase the abundance and diversity of water column flora.30 Studies have shown that the addition of sodium humate and probiotics significantly affects the microbial environment of L. vannamei in shrimp farming, effectively reducing the ammonia nitrogen and nitrite nitrogen content in the water.19 This study’s findings showed that the addition of sodium humate not only considerably increased the number of heterotrophic bacteria and promoted the growth of bioflocs in the zero-water exchange culture water body of L. vannamei and reduced the accumulation of nitrite nitrogen (NO2--N) and nitrate nitrogen (NO3--N) to a certain degree, but also significantly altered the bacterial flora of the water body composition and increased the richness of the microbial community. However, this experiment was conducted in an indoor tank, which may not be fully representative of pond aquaculture environments, and it is hoped that future research will go beyond the limitations of this paper, for example, by validating with pond scale.

CONCLUSION

A 54-day shrimp culture experiment was conducted under zero-water exchange mode with L. vannamei to investigate the effects of different concentrations of sodium humate on shrimp growth, survival, enzyme activities and microbial communities in the culture water. The conclusions showed that adding 3 mg/L and 9 mg/L of sodium humate was more appropriate considering the growth performance, SR, Vibrio population, and culture cost of shrimp. The addition of sodium humate substantially promoted the formation of bioflocs and reduced the accumulation of nitrite nitrogen (NO2--N) and nitrate nitrogen (NO3--N) in the culture water. Meanwhile, sodium humate significantly increased the activity of several enzymes in the shrimp intestine, including SOD, PO, CAT and lysozyme, thus enhancing the digestive ability and immune function of shrimp. The addition of sodium humate also increased the number of heterotrophic bacteria in the water column while reducing the number of Vibrio spp. and improving the microbial environment of the culture water. This research showed that sodium humate markedly increased the richness of the microbial community in the water body and changed the composition of the flora to some extent. In conclusion, sodium humate has pronounced positive effects in the zero-water exchange culture of L. vannamei, which can optimize the water environment and improve the growth performance and immunity of shrimp while reducing the culture cost. It also has a broad application prospect.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Key R & D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFD2401703). Special thanks to everyone who contributed to this article.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Shaolong Xie; Data curation: Wuquan Liao; Methodology: Yuhang Cui, Zexu Lin; Formal analysis and investigation: Shaolong Xie, Wuquan Liao, Yuhang Cui, Zexu Lin; Writing - original draft preparation: Shaolong Xie; Writing - review and editing: Chengbo Sun; Funding acquisition: Chengbo Sun, Ping Wang; Resources: Ping Wang; Supervision: Chengbo Sun, Ping Wang.

Competing of Interest – COPE

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical Conduct Approval – IACUC

This study did not involve vertebrate animals; the experimental protocol was conducted in accordance with the Chinese Guidelines for the Ethical Review of Aquatic Animal Research, and all procedures were carried out by trained personnel.

Informed Consent Statement

All authors and institutions have confirmed this manuscript for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All the sequencing results reported in this paper are stored in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Short Read Archive (SRA) and are stored under accession number PRJNA1202863 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra).