1. Introduction

Extensive studies in animals have demonstrated that insulin-like peptides (ILPs) can activate MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways through the ILP/IGF signaling cascade, regulating a broad range of physiological processes, including growth, development, metabolism, immunity, and reproduction.1–3 Invertebrate models, such as Drosophila melanogaster have been extensively studied, revealing the presence of eight 8 ILP genes (ILP1-8) and two receptors (InR and Lgr3).4 Notably, ILP5 produced in the ovaries and malpighian tubule of D. melanogaste, suggested a role in ovarian development.5 Furthermore, insulin-like receptors (InR) have been identified in the ovaries of other Lepidoptera species, and mutations in InR can lead to ovarian dysplasia during early vitellogenesis, indicating ILPs’ involvement in insect reproduction.2 Crustaceans and insects, both belonging to the arthropod phylum, share a close genetic relationship.6 Many key genes and signaling pathways are conserved between these groups, performing similar functions throughout evolution.7

To the best of our knowledge, insulin-like androgenic gland (IAG) has been identified as the exclusive androgenic sex hormone for regulating sexual differentiation in crustaceans. However, no other ILPs from decapod crustaceans have been reported in recent decades.8,9 With the advent of high-throughput sequencing technology, more ILP genes have been identified and characterized in crustaceans, such as Sv-ILP1 in Sagmariasus verreauxi,10 insulin-like and relaxin-like peptides in *Procambarus clarkii (*Veenstra11), Mn-ILP in Macrobrachium nipponense,12 and ILP1/ILP2 in Sinonovacula constricta.13 Notably, studies of these ILPs suggested that their roles extend beyond masculinization and testis development, potentially influencing growth and innate immune responses.

The redclaw crayfish, Cherax quadricarinatus, native to the tropical regions of northern Australia and southern New Guinea, is renowned for its large size and exceptional taste, making it one of the world’s most valuable freshwater species.14 Introduced to China in the 1990s, it quickly gained popularity among domestic breeding enterprises and consumers. Previous studies have established the role of Cq-IAG in regulating masculinization in C. quadricarinatus, with sexual reversal observed upon silencing the Cq-IAG gene.8 However, research on non-IAG ILPs and the regulatory mechanisms governing feminization maintenance and ovarian development in C. quadricarinatus remains limited.

Crustaceans possess unique endocrine systems, with most sexually dimorphic traits regulated by key reproductive hormones or peptides. In these species, insulin-like androgenic gland hormone (IAG) is a male-specific ILP, which is responsible for sexual differentiation and maintains male secondary sex characteristics.15,16 However, very little information is available regarding the function of non-IAG ILPs in female reproduction of crustaceans. For this purpose, we focused on the roles of ILPs (Cq-ILP1 and Cq-ILP2) in ovarian development in C. quadricarinatus, aiming to elucidate their potential involvement in sex differentiation and development. Relative expression levels were assessed in various tissues and developmental stages of ovaries and juveniles using qRT-PCR. Additionally, the transcriptional expression of Cq-vg was analyzed following the silencing of the Cq-ILP1 gene. These findings could provide deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms by which Cq-ILP1 regulated ovarian development.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and samples preparation

The redclaw crayfish of both sexes (n=50) used in this study were sourced from a freshwater lobster breeding base in Huzhou, China, and transferred to the laboratory for 1 week of acclimatization. Tissues, including the heart (Hea), hepatopancreas (Hep), muscle (Mu), gill (Gi), eyestalk (Eys), ovary (Ov), testis (Te), and intestines (In), were dissected from six healthy adult crayfish (average body weight: 55±10 g) on ice. Ovaries at different developmental stages (I to VI) were sampled based on biological processes and histological characteristics. Juvenile samples at various body lengths (1 cm, 2 cm, 4 cm, 5 cm, 8 cm, and 10 cm) were collected from pond-cultured crayfish at different time points, and three individuals were sampled per stage. All animal experiments that were conducted in this study were approved by the Committee of Laboratory Animal Experimentation at the Zhejiang Institute of Freshwater Fisheries, Huzhou, China.

2.2. Sequence bioinformatics analysis

The genomic structure of intron-exon composition was analyzed based on the published ILP1 (GenBank accession No. KP006644) and ILP2 (KP006645) cDNA sequences, as well as the genomic sequence of C. quadricarinatus.17 Multiple amino acid sequence alignments of ILPs were performed using DNAMAN software, comparing C. quadricarinatus and Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Signal peptides were predicted using the SignalP 3.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). Secondary protein domains and three-dimensional (3D) structures were identified using the SMART program (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and I-TASSER software (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with MEGA 5.0 software, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Protein sequences and primers used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

2.3. RNA extraction and qRT-PCR performance

Total RNA was extracted from the collected C. quadricarinatus samples using TRIzol® Reagent (Total RNA Extractor Kit, Sangon Biotech). RNA quality and concentration were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and a nucleic acid analyzer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the HiFiScript cDNA first-strand synthesis kit (Cwbio, Beijing). The cDNAs were stored at -20℃ for subsequent mRNA expression level analysis.

qRT-PCR was employed to quantify the mRNA expression levels. Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer 5 software (Table 2). qPCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 System (Roche Switzerland) in a 10 μL reaction volume containing 1 μL cDNA template, 1 μL of each primer (10 μM), 5 μL 2x SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM (TaKaRa, Japan) and 2 μL of water. The cycling conditions were as follows: initial incubation for 30 s at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s denaturation at 95°C, and 10 s extension at 60°C. Dissociation curve analysis was performed after the end of amplification to determine specific primer efficiencies. Gene expression levels were normalized to β-actin as an internal control that validated as previously described,14 and a reaction without cDNA was used as the negative control. Each reaction was performed in triplicate.

2.4. Eyestalk ablation and β-Estradiol (E2) injection assay

In this study, healthy crayfish weighing approximately 40-50 grams weight (n=12) were randomly selected for unilateral eyestalk ablation using sterile surgical scissors. The wounds were cauterized to minimize hemolymph loss, and no mortality was observed during the post-operative monitoring. Four eyestalk-ablated individuals (ESA) and four control crayfish with intact eyestalks were collected at 24 and 96 hours post-ablation, respectively, and placed in an ice bath until anesthetized. Ovarian tissues were then dissected and sampled for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis. For the β-Estradiol in vivo injection assay, estradiol (Macklin, China, purity≥98%) was dissolved in ethanol to achieve a final concentration of 50 μg/mL. The injection dosage (0.1 μg/g body weight) and volume (100 μL) followed the protocol from a previous study.18 In this experiment, the estradiol was injected into the fifth abdominal segment of female individuals (n=12), with a control group receiving the same volume of ethanol. Four crayfish from each treatment group were collected at 24 and 96 hours post-injection, anesthetized on ice, and dissected to obtain ovarian tissues for subsequent expression analysis.

2.5. RNA interference

Approximately 400 bp fragments of Cq-ILP1 and GFP were subcloned into pUC57 vectors, respectively. Specific primers with a T7 promoter were designed (Table 2), and PCR amplification was performed using plasmids as templates. The PCR products were purified and used as temples for dsRNA synthesis using the T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit (Vazyme, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the in vivo dsRNA injection experiment, female adult crayfish (n=30) were assigned two treatment groups: Cq-ILP1 dsRNA (n=15) and GFP dsRNA (n=15). Each animal was injected with 5 μg/g body weight, and ovarian tissues were collected 24 hour after injection. Finally, qRT-PCR was conducted to analyze the expression of the target genes, Cq-ILP1 and vg, in dsRNA-injected crayfish.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The qRT-PCR data were calculated using 2-ΔΔCt method19 and expressed as means ± standard. Statistical differences were estimated by one-way ANOVA followed by LSD and Duncan’s multiple range test in tissue distribution, embryonic stages, and ovary cycle. Besides, a two-side t-test was used to compare expression levels in RNAi experiments. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the redclaw crayfish ILP genes

The complete genomic sequences of Cq-ILP1 and Cq-ILP2 were obtained from the transcriptomic and genomic data of C. quadricarinatus. The exonic-intronic structure, consisting of four exons and three introns, was analyzed (Fig 1a). The predicted amino acid sequences of Cq-ILP1 and Cq-ILP2 revealed the presence of a signal peptide and conserved domains (Fig 1b). Multiple sequence alignment indicated that ILPs from C. quadricarinatus and M. rosenbergii consisted of three peptide chains and six conserved cysteine residues located within the B and A chains. The three-dimensional structures of Cq-ILP1 and Cq-ILP2 were predicted using the PDB template, as shown in Fig. 1c and 1d. Phylogenetic tree analysis demonstrated that crustaceans clustered together, with Cq-ILP sharing the closest genetic relationship with Sagmariasus verreauxi and M. rosenbergii among the examined species (Fig 1e).

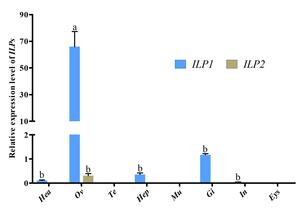

3.2. The expression pattern of ILPs in various tissues

qRT-PCR was employed to assess the transcriptional levels of Cq-ILPs in various tissues. Tissue distribution analysis revealed that Cq-ILP1 expression was highest in the ovaries, followed by the gills and hepatopancreas, while Cq-ILP2 expression was predominantly restricted to the ovaries, albeit at lower levels (Fig 2). These results indicated that Cq-ILPs were significantly more expressed in ovarian tissue, suggesting their potential involvement in female reproduction in C. quadricarinatus.

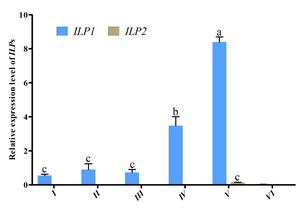

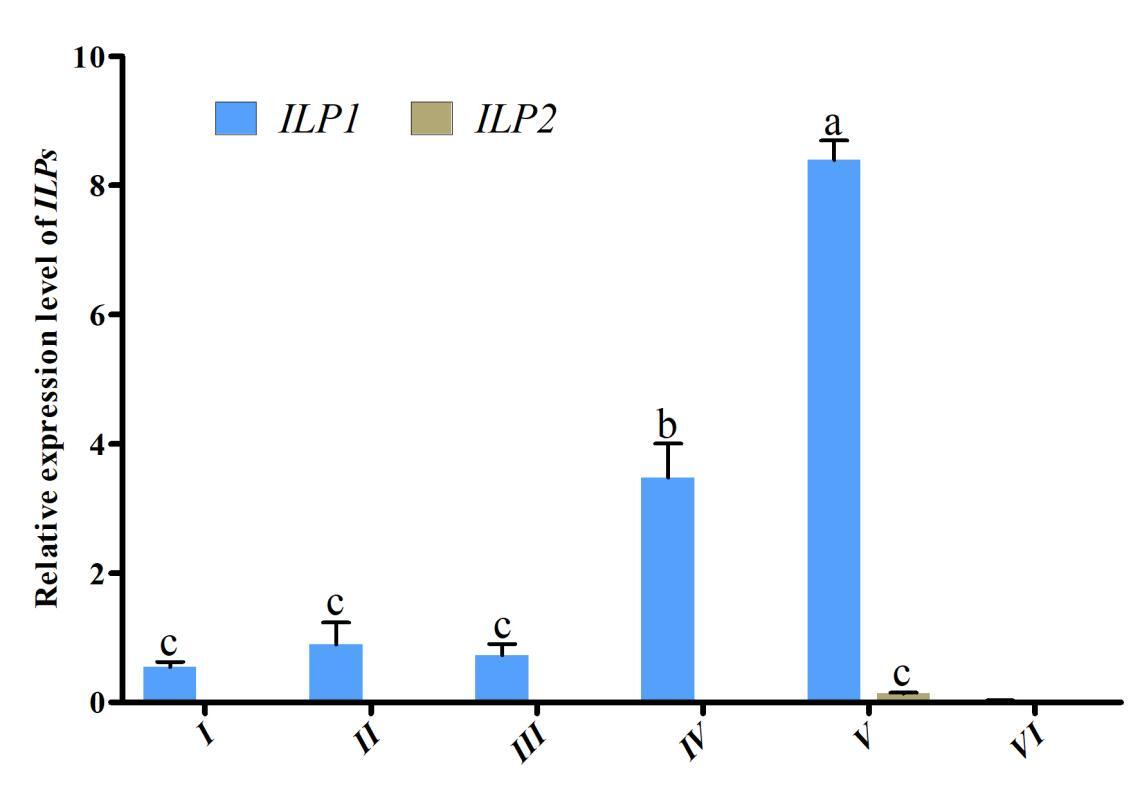

3.3. Expression of ILPs in different developmental stages of the ovaries

To investigate the role of Cq-ILPs in ovarian development, expression patterns were analyzed across different ovarian developmental stages using qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3, the highest expression level of Cq-ILP1 occurred at Stage V (ovarian maturation) and decreased to its lowest level at Stage VI (ovarian degeneration). In contrast, Cq-ILP2 was barely detectable at any stage of the reproductive cycle. These results suggested that Cq-ILP1 exhibited an ovary-specific expression pattern and is likely involved in ovarian development in C. quadricarinatus.

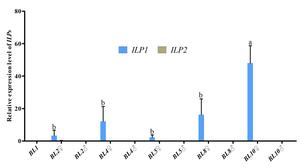

3.4. The expression profile of ILPs during embryo development

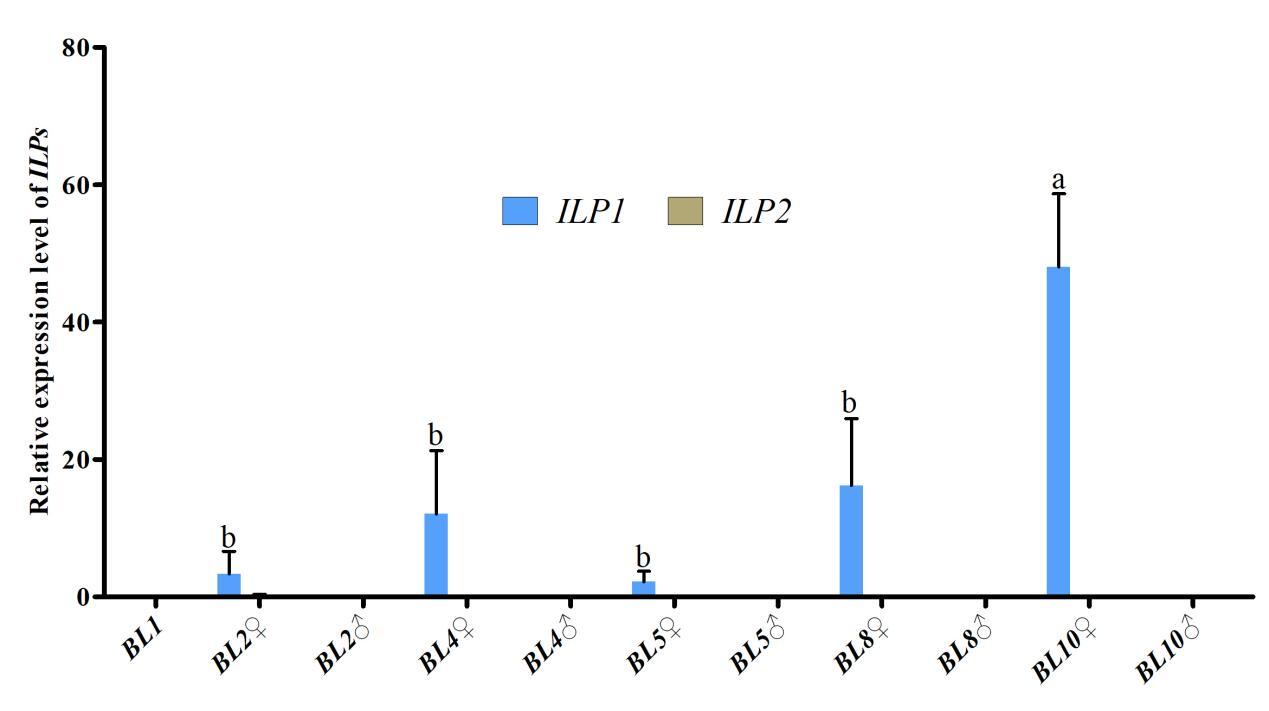

Further investigation of Cq-ILP expression during early sex differentiation revealed its expression profile at different growth stages. qPCR analysis indicated Cq-ILP1 was first detectable in female individuals at a body length of 2 cm (BL2♀), with expression levels steadily increasing throughout subsequent developmental stages. Notably, both Cq-ILP1 and Cq-ILP2 exhibited significantly lower expression levels in males at all examined stages (Fig. 4). Collectively, the spatio-temporal expression analysis of Cq-ILPs suggested that Cq-ILP1 played a critical role in ovarian development and sex differentiation in C. quadricarinatus.

3.5. The expression differences under eyestalk ablation and E2 stimulation

qRT-PCR results indicated that exogenous E2 injection significantly increased Cq-ILP1 expression at 96 hours post-treatment (P<0.01), with no significant change at 24 hours (Fig 5a). For the vg gene, exogenous E2 injection elevated expression levels at both 24 and 96 hours (Fig 5b). Additionally, the expression of Cq-ILP1 and vg in ovaries was assessed following eyestalk ablation (ESA). As anticipated, both Cq-ILP1 and vg expression levels were significantly higher in the ESA group compared to the control group.

3.6. Effects of ILP1 knockdown on vg transcription by RNAi

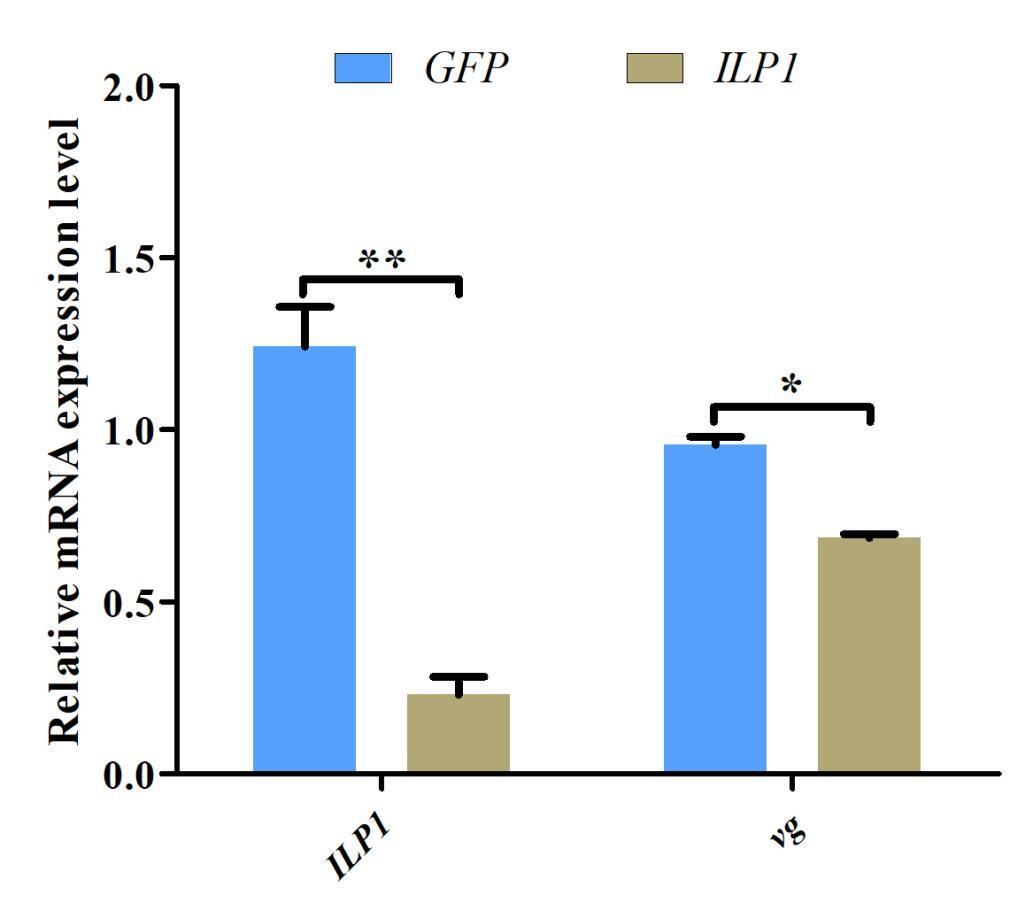

Given the potential role of Cq-ILP1 in ovarian development, RNA interference (RNAi) was used to investigate its function in female crayfish. Cq-ILP1 expression was reduced by 81.47% following injection with Cq-ILP1-dsRNA (P<0.01), confirming the success of the RNAi-mediated knockdown. The effect of Cq-ILP1 silencing on vg transcript was also assessed, and results revealed a decrease in vg abundance in the ovaries (Fig. 6). These results demonstrated that RNAi-mediated silencing of Cq-ILP1 reduced vg accumulation in the ovaries of C. quadricarinatus.

4. Discussion

In this study, sequence analysis and expression profiling of Cq-ILP1 and Cq-ILP2 in the redclaw crayfish were conducted. Previous research has shown that ILP genes in invertebrates are not derived from single-copy genes but are encoded by multiple genes.20,21 Amino acid sequences encoded by ILP genes typically share conserved structural features, including a signal peptide followed by the B, C, and A-chains, which are highly conserved within the ILP superfamily.22,23 Additionally, Cq-ILP1 and Cq-ILP2 contained conserved cysteine residues that form disulfide bonds, essential for protein function through peptide cross-linking.24 Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the ILPs from the redclaw caryfish were highly similar to those of S. verreauxi.

Insulin superfamily polypeptides regulate a broad range of functions in metazoans, including metabolism, growth, and reproduction.25,26 Studies in decapod crustaceans have suggested that ILPs play important roles in regulating growth and metabolism.12,24,27 However, the identification and role of non-IAG ILP members in crustacean reproduction remain poorly understood. Gene expression analysis is often closely linked to biological function,12 prompting the spatio-temporal expression analysis of ILPs to explore their potential roles. In this study, Cq-ILP1 exhibited high expression levels in the ovary compared to other tissues, suggesting its involvement in sexual differentiation or female reproduction. A similar pattern of ILP1 expression during ovarian development was observed in Sinonovacula constricta.13 However, studies on S. verreauxi and Tigriopus japonicus indicated higher ILP1 expression in male glands,22,27 creating a notable divergence in the redclaw crayfish. Thus, the high expression of ILP1 in C. quadricarinatus suggested its role in female sexual development, although further research was needed to generalize the function of ILPs in crustaceans. Additionally, Cq-ILP1 expression was detected in the gill, indicating its potential involvement in glucose metabolism. Although the expression level was examined in several tissues, the ILP1 expression in the ovary was much higher than in other tissues, suggesting the dominant role of ILP1 in sexual determination. While ILP1 was expressed in several tissues, its significantly higher expression in the ovary suggested its dominant role in sexual determination.

Tissue distribution analysis clearly indicated that Cq-ILP1 might play a key role in regulating ovarian development in crayfish, prompting further investigation into the expression profiles of Cq-ILPs during ovarian development. qRT-PCR results showed that Cq-ILP1 expression was significantly higher at the ripe stage compared to other ovarian developmental stages, exhibiting a consistent expression pattern with other sex-related genes, and was closely associated with ovarian development in C. quadricarinatus.14,28 Additionally, the expression of Cq-ILPs during early embryo development was also examined. qRT-PCR results revealed that Cq-ILP1 was first detected in female crayfish at a body length of 2 cm, with expression levels increasing as body size grew. Interestingly, genital pores were also observed on the third cheliped when the body length approached 2 cm. These findings suggested that sexual differentiation in C. quadricarinatus might begin at a body length of 2 cm, and the expression of Cq-ILP1 in early developmental stages can be marked as the initiating point of sexual differentiation.

The explicit mechanisms underlying sex differentiation and determination of non-IAG ILPs remain unclear in crustaceans. It has been established that vitellogenin (vg) synthesis is a key process in ovarian development in oviparous animals, with vg abundance serving as an important biomarker in studies of ovarian development in crustaceans.29–31 Endogenous ILPs and their associated signaling pathways play critical roles in regulating vg synthesis in decapod crustaceans.32 RNAi is a widely used tool for exploring gene function in crustaceans,33,34 and in this study, RNAi was employed to investigate the role of Cq-ILP1 in ovarian development. As expected, Cq-ILP1 mRNA expression was significantly inhibited following dsRNA injection, demonstrating the effectiveness of RNAi in gene silencing. Furthermore, RNAi-mediated knockdown of Cq-ILP1 significantly blocked the stimulation of vg expression, suggesting that Cq-ILP1 acted as an intermediary between insulin superfamily polypeptides and vg synthesis. These results provided strong evidence that Cq-ILP1 played a pivotal role in sex differentiation. However, further studies were required to elucidate the interaction between Cq-ILP1 and vg in the regulation of female reproduction in C. quadricarinatus.

In conclusion, two non-IAG ILP genes, Cq-ILP1 and Cq-ILP2, were characterized from C. quadricarinatus. Cq-ILP1 was predominantly expressed in the ovary, with expression detectable as early as the 2 cm body length stage, implying its involvement in sexual development. Moreover, RNAi-mediated silencing of Cq-ILP1 significantly reduced vg expression, indicating that Cq-ILP1 played a role in regulating ovarian development. These findings enhanced our understanding of insulin superfamily polypeptides and provided a valuable resource for future studies on dsRNA-mediated regulation of ovarian development in crustaceans.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Key Scientific and Technological Grant of Zhejiang for Breeding New Agricultural Varieties (2021C02069-4-5).

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Jianbo Zheng, Haiqi Zhang; Methodology: Yi Xu, Chao Zhu; Formal analysis and investigation: Wenping Jiang, Shun Cheng; Writing - original draft preparation: Yi Xu, Jianbo Zheng; Writing - review and editing: Haiqi Zhang; Funding acquisition: Meili Chi; Resources: Shili Liu; Supervision: Fei Li.

Competing of Interest – COPE

No competing interests were disclosed.

Ethical Conduct Approval – IACUC

All experiments in this study were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for scientific purposes and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Institute of Freshwater Fisheries.

Informed Consent Statement

All authors and institutions have confirmed this manuscript for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All are available upon reasonable request.