Introduction

Sea urchins, belonging to the class Echinoidea, are widely distributed across marine ecosystems around the world. They are most commonly found in shallow coastal habitats, such as rocky reefs and sandy bottoms. Their diet primarily comprises various types of algae, periphyton, and seagrass as well as benthic invertebrates.1,2 In China, sea urchins are widely distributed across coastal regions ranging from the Bohai Sea to the South China Sea. As keystone species in marine ecosystems, sea urchins contribute significantly to the aquaculture economy through their nutrient-rich gonads.3 These gonads serve as high-value nutritional resources, highlighting their dual value in both gastronomy and nutraceutical applications.4 However, climate change and habitat degradation have caused wild populations to decline sharply, prompting the accelerated development of aquaculture to meet rising market demand.5 Beyond their economic importance, sea urchins are established model organisms in developmental biology, immunology, and evolutionary research, making them valuable for elucidating the molecular mechanisms of gonad maturation under culture conditions.6

Sea urchins are not only important marine food resources but also receive considerable attention due to their unique structural composition and value as model organisms. However, systematic research on monosaccharides and trace elements within the key chemical matrix that affects their nutritional value and physiological functions is still insufficient, particularly lacking comprehensive quantitative analytical data on these components in different sea urchin species. Therefore, this study aims to accurately determine the monosaccharide profiles and trace element profiles in sea urchin gonads through modern analytical techniques, providing a scientific basis for evaluating their nutritional quality, physiological activity, and potential environmental health risks. At the physiological function level, monosaccharides serve as fundamental building blocks of bioactive macromolecules, and their monomeric forms that exist independently have also been demonstrated to possess immunomodulatory activity. Although early studies primarily focused on how monosaccharide sequences within polysaccharide structures affect immune responses,7 recent advances in glycobiology have revealed that free monosaccharides themselves may exert specific immunoregulatory functions through different signaling pathways,8 a mechanism that remains to be thoroughly explored in marine invertebrates. Trace elements are also indispensable components for maintaining metabolic homeostasis in sea urchins, participating in various life activities as cofactors for multiple enzymatic reactions.9 It is noteworthy that the requirements and toxic responses to trace elements in marine organisms are distinctly species-specific: essential elements are crucial for physiological balance at appropriate concentrations, while non-essential elements, including heavy metals, exert dose-dependent toxic effects through bioaccumulation. Research has shown that marine metal pollutants can disrupt biochemical pathways in echinoderms, resulting in morphological, physiological, and behavioral abnormalities.10,11 The primary toxic mechanisms involve the inhibition of enzyme active sites and the displacement of essential metal cofactors within biomolecules. Given the above background, accurate quantification of monosaccharides and trace elements in sea urchin gonads not only helps evaluate their nutritional and immunological value but also provides sensitive biomarkers for monitoring the accumulation of marine pollutants in organisms. However, interspecific comparative studies on monosaccharides and trace elements in sea urchins remain extremely limited internationally, especially with systematic data on commercially cultured sea urchin species in China being almost absent. This largely restricts the evaluation of nutritional quality, selective breeding, and the development of functional products in China’s sea urchin industry.

To this end, this study selected four representative commercial sea urchin species in China—Strongylocentrotus intermedius, Mesocentrotus nudus, Glyptocidaris crenularis, and Anthocidaris crassispina—as research subjects. Addressing the characteristics of complex matrix and low target content in sea urchin gonads, we employed inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and ion chromatography (IC) techniques to establish highly sensitive quantitative analytical methods for trace elements and monosaccharides, respectively. Through systematic comparison of the monosaccharide profiles and trace element profiles in the gonads of these four sea urchin species, this study aims to: (1) clarify the nutritional chemical characteristics of different sea urchin species; (2) elucidate the specific distribution patterns of trace elements in their gonadal tissues; and (3) provide fundamental data for evaluating the nutritional advantages and potential heavy metal exposure risks of sea urchins as functional food ingredients, thereby supporting quality grading and high-value utilization of sea urchin resources.

Materials and Methods

Materials

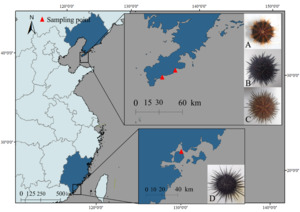

Four sea urchin species were collected from coastal regions in China: S. intermedius and G. crenularis: Longwangtang, Dalian (38.847°N, 121.413°E); M. nudus: Xinghai Park, Dalian (38.881°N, 121.587°E); A. crassispina: Jimei, Xiamen (24.578°N, 118.092°E) (Figure 1). Biometric measurements (Table 1) were performed on three randomly selected healthy individuals per species (n = 3 biological replicates per species, total n = 12) prior to further analysis.

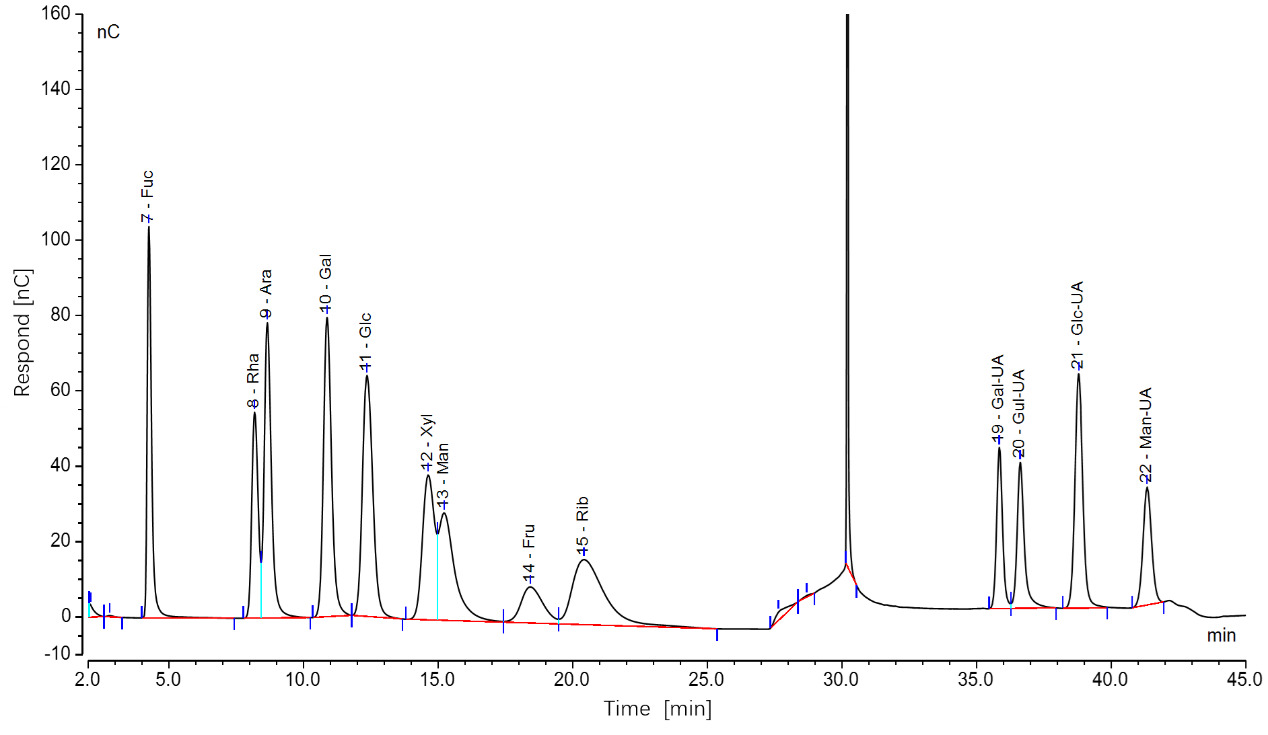

Determination of Monosaccharides

Accurately weighed 4.0 mg of each monosaccharide standard (Fucose, Glucose, Xylose, Fructose, Ribose, Galactose, Mannose, Rhamnose, Arabinose, Galacturonic Acid, Glucuronic Acid, Mannuronic Acid, Guluronic Acid) and dissolved in ultrapure water to prepare individual stock solutions at 10 mg/mL. Mixed standard solutions at final concentrations of 0.04, 0.05, and 0.06 mg/mL were prepared by serial dilution using the XH-T Vortex Mixer (Baita Xinbao Instrument Factory). A six-point calibration curve (0.01-0.06 mg/mL) was generated by proportionally combining the stocks solutions. For sample preparation, anhydrous ethanol was added to the samples and vortexed for 5 min for pigment removal to eliminate matrix interference. The mixture was centrifuged at 3000×g for 10min, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended in sterile water and subjected to extraction at 70℃ for 2h to ensure complete dissolution. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and dried under nitrogen gas using a Reacti-Thermo evaporator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The residue was hydrolyzed in 1mL 2M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at 121℃ for 2h, followed by drying under nitrogen gas. The product was washed with HPLC-grade methanol and reconstituted in sterile water for analysis. Monosaccharide composition was determined using an ICS 5000+ ion chromatography system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a Dionex™ CarboPac™ PA20 column (150 × 3.0 mm, 10 μm) and an electrochemical detector. A 5 μL injection volume was used, with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The ternary mobile phases included: (A) ultrapure water, (B) 0.1 M NaOH, and (C) 0.1 M NaOH / 0.2 M sodium acetate (NaAc). The column temperature was maintained at 30°C under the following gradient program: 0-26min (95:5:0 → 85:5:10), 26-42min (isocratic), 42.1-52min (60:0:40 → 60:40:0), 52.1-60min (re-equilibration at 95:5:0). The methods and specific parameters for monosaccharide determination were referenced from Zhu et al.12

Determination of Trace Elements

The polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) microwave digestion vessels were pretreated by soaking in hot aqua regia for 30 min. Precisely weighed 0.1000g of sample (accuracy ±0.0001g) using an analytical balance and transferred into an 80 mL PTFE digestion vessel to ensure complete acid contact. After moistening the sample with deionized water, 6mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl), 2mL of nitric acid (HNO₃), and 4mL of hydrofluoric acid (HF) were added sequentially. The vessel was then placed in the microwave digestion system and subjected to a heating program, maintaining a maximum temperature of 195℃ for 2h, then cooled to room temperature, and the digested solution was transferred to a 25mL PTFE volumetric tube. The solution was brought to volume, thoroughly mixed, and allowed to stabilize before undergoing instrumental analysis. A blank sample was prepared using the same method. Elemental analysis was conducted using an Agilent 8900 ICP-MS (Agilent Technologies, USA). The relevant parameter settings were as follows: RF Power set at 1550 W; plasma flow at 12000 mL/min; auxiliary gas flow at 850 mL/min; nebulizer gas flow at 350 mL/min. The sample uptake delay was 14 seconds, and the instrument stabilization delay was 10 seconds. The Replicate read time was 0.5s. The multi-element standard solution (100 mg·L⁻¹ in 5 % HNO₃) was supplied by NCS Testing Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Calibration curves for all 20 elements exhibited correlation coefficients (R²) ≥ 0.99, meeting the requirements of certified reference materials. The determination method was performed in accordance with the requirements specified in GB 5009.268-2016 (National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Multi-elements in Foods).13

Sample project: Calcium (Ca), Zinc (Zn), Iron(Fe), Aluminum (Al), Copper (Cu), Vanadium (V), Manganese (Mn), Selenium (Se), Cobalt (Co), Molybdenum (Mo), Boron (B), Lithium (Li), Arsenic (As), Chromium (Cr), Nickel (Ni), Cadmium (Cd), Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Silver (Ag), Tin (Sn).

Data Processing

Biometric data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates per species, total n = 12). All data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variances prior to analysis. Given the small sample size (n = 3 per species) and non-normal distribution of some parameters, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the four sea urchin species. Pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s post-hoc test with the Bonferroni correction. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0. Graphical representations were generated using Excel 2019, ArcGIS 10.7, and Chromeleon 7.3.

Results

Monosaccharide Composition Analysis of Sea Urchin

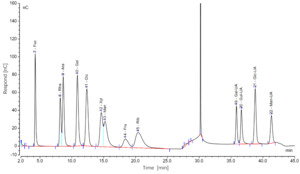

The chromatographic data, processed using Chromeleon software, yielded ion chromatograms of the standard samples, showing baseline-separated, symmetrical peaks for all 12 monosaccharides (Figure 2). Ten monosaccharides were identified in sea urchin gonads, including fucose (Fuc), glucose (Glc), ribose (Rib), galactose (Gal), mannose (Man), rhamnose (Rha), arabinose (Ara), and glucuronic acid (Glc-UA). Despite intergroup variations in peak areas, the retention times and number of peaks remained consistent. Quantitatively, glucose content was 2.7- to 3.5-fold higher than that of mannose, which in turn exhibited 4.8- to 6.1-fold higher concentrations compared to the other detected monosaccharides.

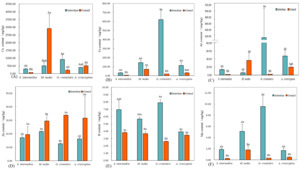

The total monosaccharide content in the gonads of four sea urchin species was quantified as follows: S. intermedius (90.50 ± 9.10 μg/mg), M. nudus (95.58 ± 37.37 μg/mg), G. crenularis (93.82 ± 4.29 μg/mg), and A. crassispina (74.94 ± 9.96 μg/mg). Glucose and mannose were the predominant monosaccharides, with glucose accounting for 60.37–71.74% of the total content significantly higher than mannose (23.79–35.80%; P < 0.05). The remaining monosaccharides collectively comprised less than 15% of the total (Figure 3).

A. crassispina exhibited the lowest glucose content (51.09±23.43 μg/mg; P<0.05), while S. intermedius, G. crenularis, and M. nudus showed comparable glucose levels (P>0.05). Mannose was the second most abundant monosaccharide across all species (21.40-27.20 μg/mg), with no significant differences observed among them (P>0.05) (Figure 4(A)).

In the four sea urchin species, the content of fucose, galactose, and ribose was relatively low, accounting for 0.2-3.93%. The concentration of fucose ranged from 0.26 μg/mg to 0.85 μg/mg, with no significant differences among species (P>0.05). Galactose content was highest in M. nudus (1.82±0.28 μg/mg; P<0.05), while S. intermedius, G. crenularis, and A. crassispina showed similarly low levels, with no significant differences among them (P>0.05). Ribose content followed the order: S. intermedius > G. crenularis > M. nudus > A. crassispina, with S. intermedius showing the highest concentration (1.76±0.27 μg/mg; P<0.05) (Figure 4(B)).

The content of rhamnose, arabinose, and glucuronic acid was very low, all accounting for less than 1% of the total monosaccharides content in the four sea urchin species (Figure 4(C)). The rhamnose content was highest in S. intermedius (0.43±0.08 μg/mg), followed by G. crenularis (0.29±0.08 μg/mg), and the lowest in M. nudus (0.21±0.02 μg/mg). It was not detected in A. crassispina. The arabinose content was relatively consistent across species, with the highest level observed in A. crassispina (0.08±0.04 μg/mg), but no significant differences were found among groups (P>0.05). Glucuronic acid content was higher in A. crassispina and M. nudus, with no significant difference between others (P>0.05), while S. intermedius exhibited the lowest level (0.24±0.03 μg/mg; P<0.05).

Trace Element Content in Sea Urchin

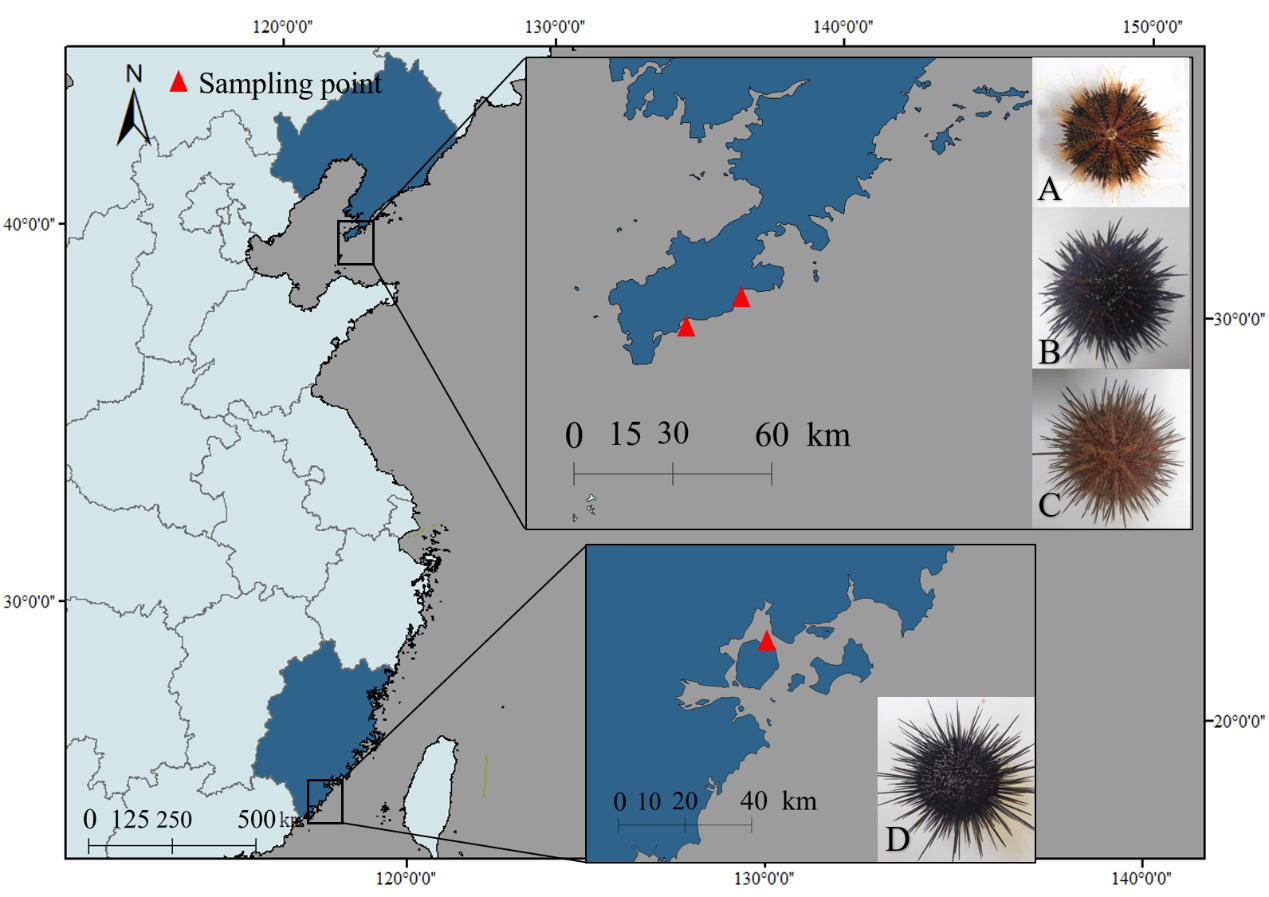

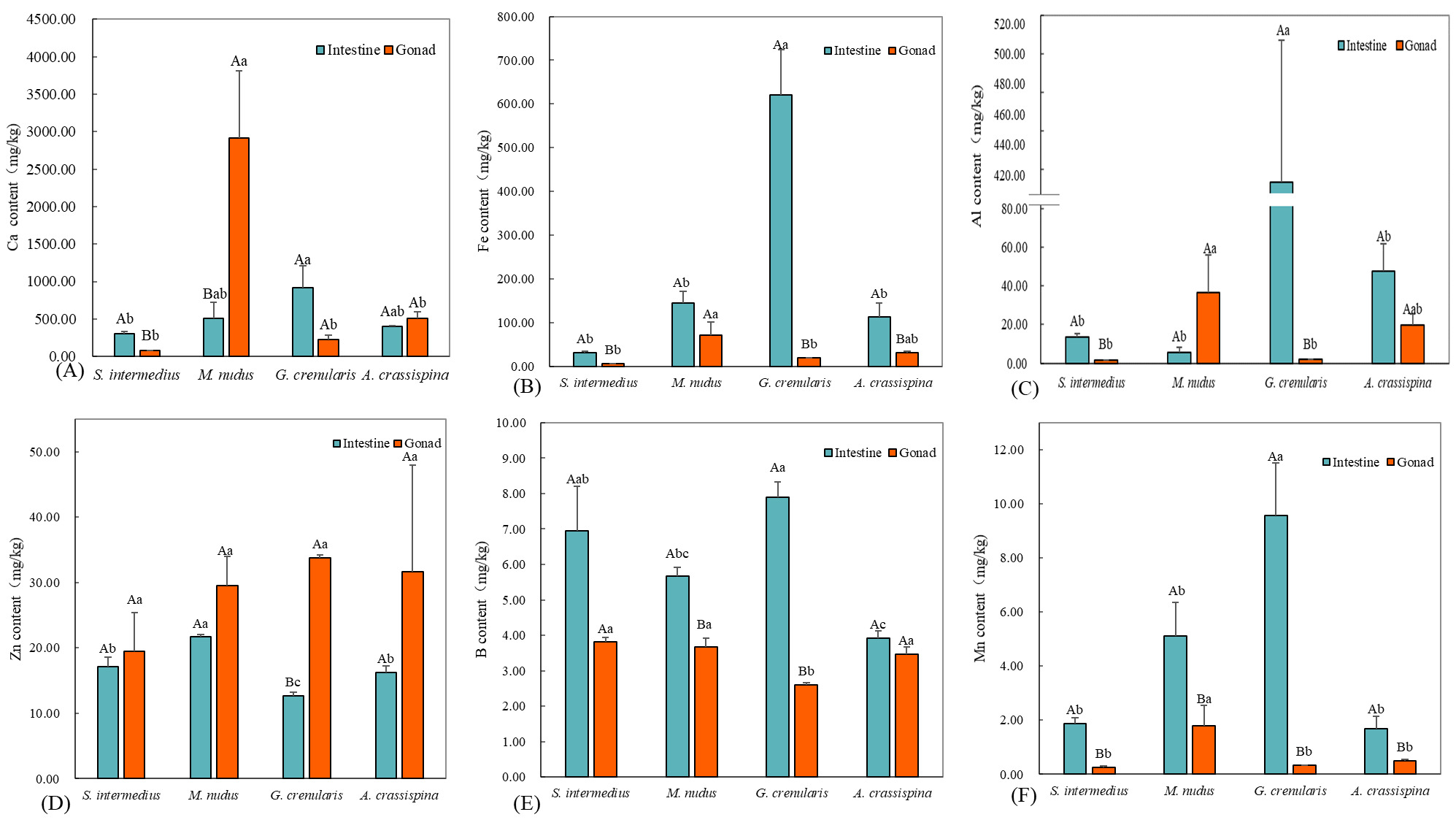

We quantified 20 trace elements across four sea urchin species and classified them into two functional categories based on biological effects. The proportional distributions of the essential and potentially toxic trace elements in the intestine and gonad of the sea urchins are illustrated in Figure 5, respectively. Essential elements (12): Ca, Zn, Fe, Al, Cu, V, Mn, Se, Co, Mo, B, and Li (Figure 6). These micronutrients are crucial for maintaining metabolic homeostasis and supporting key physiological functions. Potentially toxic elements (8): As, Cr, Ni, Cd, Pb, Hg, Ag, and Sn (Figure 7). Although some of these elements may have beneficial effects at trace levels, all exhibit dose-dependent toxicity thresholds that can compromise organismal viability when exceeded.

Among the four sea urchin species, essential elements Ca, Fe, Al, and Zn exhibited elevated concentrations with distinct tissue-specific distribution patterns. Ca concentrations in the intestine ranged from 12 to 920 mg/kg, while gonadal levels varied between 2 and 510 mg/kg. Notably, M. nudus displayed minimal Al content in the intestine (5.48±2.86 mg/kg), whereas its gonadal Ca reached 2911.34±902.13 mg/kg, significantly exceeding intestinal levels (P<0.05). In contrast, S. intermedius exhibited higher intestinal Ca (914.92±292.67 mg/kg) compared to gonadal levels (300.04±34.07 mg/kg; P<0.05). No significant gonad-intestine Ca differences were observed in A. crassispina and G. crenularis (P>0.05). Interspecifically, intestinal Ca peaked in G. crenularis (914.92±292.67 mg/kg), significantly exceeding the lowest value observed in S. intermedius (300.04±34.07 mg/kg; P<0.05). The gonadal Ca concentration in M. nudus (2911 mg/kg) showed no statistically significant similarity to those of the other species (P > 0.05). Fe content was significantly higher in intestines than in gonads for S. intermedius, G. crenularis, and A. crassispina (P<0.05), while M. nudus showed no tissue-specific difference (P>0.05). Intestinal Fe was highest in G. crenularis (620.17±104.13 mg/kg, P<0.05), with no significant interspecific difference among other species (P>0.05). Gonadal Fe was highest in M. nudus (70.73±30.10 mg/kg), significantly differing from both S. intermedius (6.11±0.38 mg/kg) and G. crenularis (19.25±0.55 mg/kg, P<0.05). Al content exhibited intestinal predominance in S. intermedius and G. crenularis (P<0.05), whereas M. nudus and A. crassispina displayed comparable levels between tissues (P>0.05). The highest intestinal Al concentration was observed in G. crenularis (433.61±73.57 mg/kg), while gonadal Al peaked in M. nudus (36.65±19.53 mg/kg). The lowest gonadal Al levels were recorded in S. intermedius (1.66±0.08 mg/kg) and G. crenularis (1.78±0.28 mg/kg). Zn showed significant gonadal accumulation in G. crenularis and A. crassispina (P<0.05), with no tissue-specific preference observed in S. intermedius or M. nudus (P>0.05). Intestinal Zn concentrations ranged from 12.69±0.47 mg/kg (G. crenularis) to 21.65±0.35 mg/kg (M. nudus, P<0.05), while gonadal Zn levels displayed interspecific uniformity (P>0.05).

Concentrations of B, Mn, and Cu generally ranged from 0.5 to 9.5 mg/kg. Intestinal B levels were significantly higher than gonadal levels in S. intermedius, M. nudus, and G. crenularis (P < 0.05). The highest intestinal B concentration was found in G. crenularis (7.90 ± 0.42 mg/kg). In the gonads, G. crenularis had the lowest B concentration (2.60 ± 0.06 mg/kg; P < 0.05), while the other species showed comparable levels (P > 0.05). All species exhibited significantly higher Mn concentrations in the intestine compared to the gonads (P < 0.05). The highest intestinal Mn level was observed in G. crenularis (9.57 ± 1.94 mg/kg; P < 0.05). Among gonads, M. nudus had the highest Mn concentration (1.80 ± 0.75 mg/kg; P < 0.05), with no significant interspecific differences among the remaining species (P > 0.05). Intestinal Cu levels were significantly higher than gonadal levels across all species (P < 0.05). The highest intestinal Cu concentration occurred in M. nudus (3.41 ± 0.14 mg/kg; P < 0.05), while in the gonads, G. crenularis showed the highest Cu concentration (2.51 ± 0.21 mg/kg), significantly exceeding those of others (P < 0.05).

Essential elements Mo, Se, V, Co, and Li were present at low concentrations (0.004–1.00 mg/kg), with notable differences between intestinal and gonadal tissues. Intestinal Mo exceeded gonadal levels in all species (P < 0.05), peaking in M. nudus (1.12 ± 0.02 mg/kg) and A. crassispina (1.07 ± 0.16 mg/kg), significantly higher than S. intermedius (0.40 ± 0.05 mg/kg). In gonads, M. nudus had the highest Mo level (0.08 ± 0.02 mg/kg). Intestinal Se peaked in S. intermedius (0.59 ± 0.02 mg/kg) and was lowest in A. crassispina (0.05 ± 0.01 mg/kg). Gonadal Se was lowest in A. crassispina (0.09 ± 0.01 mg/kg; P < 0.05). Intestinal V dominance was observed only in G. crenularis (0.75 ± 0.10 mg/kg; P < 0.05). Gonadal V peaked in A. crassispina (0.26 ± 0.03 mg/kg), significantly higher than in S. intermedius and G. crenularis. Intestinal Co was higher in S. intermedius and G. crenularis (P < 0.05), and gonadal Co was highest in M. nudus and G. crenularis. Intestinal Li dominated in S. intermedius (1.05 ± 0.60 mg/kg). Gonadal Li was highest in M. nudus (0.09 ± 0.02 mg/kg), significantly greater than in G. crenularis (0.03 ± 0.001 mg/kg).

Compared to essential elements, potentially toxic elements were present at lower concentrations across the four sea urchin species, with clear interspecific and tissue-specific differences. As and Cd were the dominant toxic elements, with intestinal levels ranging from 1.00–6.00 mg/kg, while gonadal Cd remained low (0.04–0.12 mg/kg). S. intermedius showed significantly higher As in the intestine (6.07 ± 0.11 mg/kg; P < 0.05), whereas A. crassispina exhibited gonadal accumulation (4.70 ± 0.45 mg/kg; P < 0.05). No significant tissue differences were found in M. nudus and G. crenularis (P > 0.05). Intestinal As was lowest in A. crassispina (1.59 ± 0.16 mg/kg) and G. crenularis (2.18 ± 0.38 mg/kg; P < 0.05). Gonadal As levels were comparable among species, except for S. intermedius (P > 0.05). Intestinal Cd was significantly higher than gonadal Cd in all species (P < 0.05), peaking in G. crenularis (2.37 ± 0.19 mg/kg) and lowest in M. nudus (0.63 ± 0.04 mg/kg; P < 0.05). Gonadal Cd was slightly higher in A. crassispina (0.12 ± 0.04 mg/kg), with no significant variation among other species (P > 0.05).

Potentially toxic elements Ni, Hg, Cr, Pb, Ag, and Sn were detected at low concentrations (0.004–0.70 mg/kg), with pronounced interspecific variation. S. intermedius and A. crassispina showed intestinal Ni dominance (P < 0.05), while G. crenularis exhibited gonadal accumulation (8.53 ± 0.81 mg/kg; P < 0.05). No tissue preference was observed in M. nudus. Intestinal Ni peaked in G. crenularis (0.63 ± 0.08 mg/kg) and was lowest in M. nudus (0.03 ± 0.02 mg/kg). Intestinal Hg was higher in all species (P < 0.05), with a maximum in G. crenularis (1.20 ± 0.42 mg/kg). Gonadal Hg ranged from 0.003 ± 0.001 mg/kg (S. intermedius) to 0.07 ± 0.01 mg/kg (A. crassispina). Intestinal Cr dominated in G. crenularis and A. crassispina (P < 0.05), peaking in G. crenularis (0.69 ± 0.10 mg/kg). No tissue-specific differences were found in S. intermedius and M. nudus, and gonadal Cr levels were similar across species. All species showed intestinal Pb accumulation (P < 0.05), highest in A. crassispina (0.42 ± 0.12 mg/kg) and lowest in S. intermedius (0.01 ± 0.002 mg/kg). Gonadal Pb was also highest in A. crassispina (0.10 ± 0.02 mg/kg). Intestinal Ag was significantly higher in S. intermedius, M. nudus, and A. crassispina (P < 0.05). Gonadal Ag peaked in G. crenularis (0.10 ± 0.03 mg/kg), with no interspecific differences among the others. Intestinal Sn was elevated in S. intermedius and G. crenularis (P < 0.05), lowest in M. nudus. Gonadal Sn was highest in A. crassispina (0.06 ± 0.01 mg/kg), while other species showed no significant variation.

Discussion

Interspecific Monosaccharide Variability and Adaptive Significance in Sea Urchins

This study revealed consistent monosaccharide profiles across the gonads of four sea urchin species, with concentration-dependent variations suggesting species-specific patterns adapted to different ecological niches. S. intermedius, M. nudus, and G. crenularis exhibited significantly higher monosaccharide levels—particularly mannose (23.79–35.80%), ribose (0.28–3.93%), and rhamnose (0.21–0.43 μg/mg)—compared to A. crassispina (P < 0.05).

Given the known immunomodulatory functions of these saccharides, including heparin-like anticoagulant activity and mannose receptor-mediated enhancement of phagocytosis, these three species may offer superior bioactive potential for modulating innate immunity, though the total glycoprotein content and in vivo bioavailability were not measured, which limits this interpretation. Notably, their enriched monosaccharide profiles were associated with potent thrombin inhibition (IC₅₀: 12-18 μg/mL) and suppression of TNF-α production (38–42% at 100 μg/mL).

Glucose was the dominant monosaccharide in sea urchin gonads, accounting for over 60% across four species. As a key hexose, it plays multiple roles, serving as a primary metabolic energy source via glycolysis/TCA cycle, a structural component in glycan biosynthesis, and a precursor for nucleotide sugar intermediates, reflecting the high metabolic demand of gametogenesis. Supporting this, Cao et al. identified glucose and mannose as major components in S. intermedius gonad polysaccharides via PMP-HPLC,14 while Yang et al. isolated glucosamine from SUGP (Polysaccharide from gonad of sea urchin), confirming its role in glycosaminoglycan assembly. Additionally, conserved fucose levels (0.26-0.85 μg/mg; P>0.05) across species suggest a potential role in hemostasis modulation, possibly contributing to reduced thrombotic risks.15,16

Ribose (0.28-3.93%), essential for nucleotide biosynthesis, was significantly more abundant in S. intermedius, M. nudus, and G. crenularis than in A. crassispina (P<0.05). This interspecific variation may reflect shower metabolic rates in colder northern habitats, a hypothesis supported by temperature-dependent metabolic rates in ectotherms, though differences in feeding and digestion could also contribute.17 Similar trends were observed for mannose (23.79-35.80%) and rhamnose (0.21-0.43 μg/mg). Mannose, a core component of N-glycan structures (Man GlcNAc₂-Asn),18 is linked to increased glycoprotein diversity, suggesting enhanced nutritional value and bioactivity, such as pathogen-associated molecular pattern recognition (IC₅₀ 12-18 μg/mL for LPS binding inhibition), which may support embryonic development, a key fitness component for broadcast spawners.

Rhamnose was highest in S. intermedius (0.43±0.08 μg/mg; P<0.05), present in M. nudus (0.21±0.02 μg/mg) and G. crenularis (0.29±0.08 μg/mg), but undetected in A. crassispina (LOD: 0.01 μg/mg by HILIC-ELSD), possibly reflecting a trade-off between reproduction and metabolic flexibility in stable, warm environments. Rhamnose-binding lectins (RBLs), conserved across metazoans, mediate innate immune responses through pathogen-associated molecular pattern (RAMP) recognition. Clinically, rhamnose forms the immunodominant epitope of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 23F capsular polysaccharide (CPS23F), inducing opsonic antibody titers >1:64 in 89% vaccinated adults. These dual roles—as lectin ligands and antigenic determinants—highlight rhamnose’s significance in combating microbial infections across species.

We hypothesize that dietary variations, coupled with thermal gradients, plays a key role in shaping gonadal monosaccharide profiles in sea urchins, However, cause-effect cannot be established from these data, and gut microbiome processing is another possible regulatory factor. Northern species (S. intermedius, M. nudus, G. crenularis) primarily consume Laminaria japonica, Undaria pinnatifida, and Porphyra haitanensis,19,20 while southern species feed on Sargassum hemiphyllum, Eucheuma, Gelidium, and Caulerpa lentillifera.21,22 These macroalgae differ markedly in polysaccharide composition: northern species are rich in laminarin (β-1,3-glucan, 18-22%), whereas southern algae are rich in sulfate carrageenans (κ/ι-types, 25-28%), potentially contributes to observed monosaccharide differences, though direct dietary manipulation studies are needed to confirm this link. Interspecific digestive adaptations may further influence the efficiency of polysaccharide hydrolysis. Notably, gonad maturation stages (pre-/post-spawning) were not controlled in this study. Future work should incorporate histological staging and temporal sampling to disentangle dietary from developmental influences on carbohydrate metabolism.

Trace Element Adaptation Strategies in Sea Urchins

Trace element metabolism represents a key physiological trait that enables sea urchins to adapt to various ecological niches. By analyzing intestinal and gonadal tissues of four species, this study examined interspecific differences in element distribution, verified the “reproductive priority” strategy,23 and highlighted species-specific adaptations to toxic elements.

The gonads contained high levels of Ca, Fe and Zn, which are involved in important biological functions such as neurotransmission, oxygen transport, energy metabolism and enzyme synthesis. In M. nudus, Ca and Fe levels were highest, reflecting their roles in oocyte maturation and increased oxygen demand during gametogenesis. However, direct evidence linking these elevated levels to enhanced reproductive output would require controlled breeding experiments. Zn enrichment across species underscores its catalytic roles in proliferation and proteostasis, with M. nudus oocytes showing efficient uptake mediated by ZIP transporters. Research by Limatola24 demonstrated that Ca²⁺ signaling is essential for triggering cortical granule release during sea urchin oocytes development. Conversely, the lowest intestinal Ca content observed in S. intermedius may help maintain intestinal ion balance and support the expression of the major yolk protein (MYP) gene in the gonads, thereby ensuring the normal transport of MYP from the digestive tract to the gonads,25,26 though this proposed mechanism remains speculative without direct measurement of MYP expression or Ca transporter activity Fe facilitates nutrient transport and supplies electron carriers for embryonic mitochondrial respiratory chains, consistent with heightened oxygen consumption during sea urchin embryogenesis.27

G. crenularis exhibited high intestinal Fe, Al, V, and Mn, likely linked to sediment feeding, which suggests passive accumulation from ingested particles rather than active homeostatic regulation. The species also showed significantly greater gonadal Zn accumulation than intestinal levels, indicating selective sequestration despite high ambient exposure. Cu was consistently higher in intestines, aligning with its role in hemocyanin synthesis and microbiota regulation. As an essential cofactor for carbonic anhydrase and alkaline phosphatase, zinc (Zn) serves catalytic roles in cellular proliferation and proteostasis, mediating nucleic acid synthesis, enzymatic activity modulation, and cellular proliferation/repair mechanisms. The gonadal enrichment of Zn likely reflects increased demand for DNA synthesis during oogenesis.

Intestinal Cu levels were significantly higher than gonadal levels across all four species (P<0.05). This parallels crustaceans, where Cu is essential for hemocyanin synthesis and its oxygen-binding function. By binding to bacterial surface molecules, hemocyanin suppresses microbial growth, highlighting Cu’s role in maintaining intestinal microbiota balance.28

Intestinal concentrations of Cd, Ag, Pb, and Hg were higher than in gonads, suggesting that sea urchins limit gonadal exposure to harmful elements to safeguard embryonic development, either through active transport barriers or differential tissue binding affinity. Inorganic As is also detoxified via conversion to less toxic organic forms (MMA, DMA), while gut microbes may enhance heavy metal resistance by upregulating cysteine-rich peptides and metallothioneins.29 Notably, G. crenularis showed gonadal Ni levels 15-fold higher than intestinal levels, and A. crassispina accumulated significantly more Cd in gonads (P<0.05), suggesting these species may have compromised detoxification capacity or distinct metal handling pathways that warrant further investigation.

Trace elements are fundamental to animal physiology, serving as structural components and cofactors in proteins and enzymes, and regulating key metabolic processes, but their optimal concentrations and toxicity thresholds remain poorly defined for most marine invertebrates. For sea urchins, elements such as Ca, P, and Zn are particularly important for shell formation and reproduction,3 yet their mineral requirements remain largely uncharacterized. By analyzing intestinal and gonadal tissues, this study identified 11 essential elements—Ca, Zn, Fe, Al, Cu, V, Mn, Se, Co, Mo, and B—that play key roles in growth, development, and metabolism. Zn and Cu act as cofactors for numerous redox enzymes, while Li may regulate the nervous system.30,31 However, excess Fe, Al, and B can exert toxic effects.32

Element distribution varied significantly among species. In S. intermedius, Ca, Fe, Al, Cu, Mn, Co, and Mo were higher in intestines; in M. nudus, Ca and Se were enriched in gonads, whereas Cu, Mn, Mo, and B dominated intestines. G. crenularis showed gonadal enrichment of Zn and Se, but intestinal enrichment of Fe, Mn, Cu, Al, V, Co, Mo, and B. In A. crassispina, Se was higher in gonads, while Fe, Mn, Cu, and Mo were higher in intestines. These patterns reflect species-specific metabolic priorities and suggest dietary adjustments: M. nudus may benefit from higher Ca, Mn, Mo, and B; G. crenularis from Zn and Se; and A. crassispina from Se supplementation. Intestinal-gonadal differences may also arise from variation in gut microbiota or gene expression, factors not examined here but known to influence metal absorption in marine invertebrates.33

Toxic elements including As, Cr, Ni, Cd, Pb, Hg, Ag, and Sn were also detected, with Cd and Hg disrupting normal physiology34,35 and Sn impairing intestinal function and microbiota balance.36 Effective aquaculture practices are therefore essential—such as controlling feed composition and water quality, minimizing contact with sediments, managing stocking density, and preventing excreta accumulation—to reduce heavy metal bioaccumulation. Oystery farming studies highlight how bio-deposition and hydrodynamics influence trace element enrichment in sediments,37 offering useful parallels for sea urchin cultivation. These findings deepen understanding of species-specific trace element requirements and provide guidance for optimizing nutrition and safety in sea urchin aquaculture.

Nutritional Value of Interspecific Trace Elements

Research on trace elements in sea urchin gonads has largely focused on nutrient composition and physiological functions, given their relevance to human health. Elements such as Ca, Zn, Fe, Cu, Se, Mn, Co, and Mo are particularly beneficial, and their accumulation reflects dietary intake from macroalgae.38

In this study, M. nudus gonads contained significantly higher Ca and Mn levels than other species (P<0.05), with Fe, Al, and Mo exceeding those of S. intermedius and G. crenularis (P<0.05). Co was also enriched compared to S. intermedius and A. crassispina (P<0.05), suggesting potential species-specific homeostatic set points or differential nutrient absorption efficiencies, a hypothesis that requires controlled feeding studies to verify. Previous analyses confirmed Ca, Zn, Na, and Fe as the dominant elements in M. nudus gonads,39 consistent with our findings and supporting the reproducibility of element profiling in this species. In A. crassispina, V was significantly elevated, while Se was lowest among species (P<0.05); Zn was identified as its most abundant trace element.40 G. crenularis showed significantly higher Cu and lower B levels (P<0.05), consistent with reports of Zn dominance in this species,41 raising questions about the balance between Cu-dependent hemocyanin production and potential B toxicity avoidance mechanisms. Across all species, Zn content showed no significant differences (P>0.05).

Trace elements in sea urchin gonads are functionally important: Zn and Se support antioxidant defenses42; Ca regulates neural inhibition, immunity, and cardiovascular health43; Co is essential for vitamin B12 and hematopoiesis; Cu and Fe are critical for electron transport and enzyme activity, with deficiencies linked to anemia and metabolic disorders44; and Mo functions as a cofactor for redox enzymes and is associated with cardiovascular protection.45 These findings highlight both interspecific variation in element profiles and the potential of sea urchin gonads as high-quality dietary sources of essential trace elements. However, this potential hinges on bioaccessibility after processing and cooking, which were not evaluated, and on ensuring that toxic element accumulation does not offset the nutritional benefits.

Conclusions

This study examined the monosaccharide composition and 20 trace elements in the gonads and intestines of four Chinese sea urchin species (S. intermedius, M. nudus, G. crenularis, and A. crassispina), revealing that monosaccharides, through their structural specificity within polysaccharides, play a pivotal role in immune regulation. These findings provide a foundation for developing targeted immunotherapeutics and nutraceuticals, with future research focusing on molecular pathways and clinical applications of monosaccharide-mediated immune enhancement. The analysis of toxic elements further uncovered species-specific adaptations in metal tolerance, while comparisons of nutritional profiles showed that S. intermedius, M. nudus, and G. crenularis possess higher carbohydrate value and more substantial immunological benefits. All four species were rich in essential elements such as Ca, Fe, Zn, and Cu, with M. nudus exhibiting significantly higher Al and Mn in gonads, and G. crenularis showing elevated levels of Se, underscoring their potential as functional foods for disease prevention. Collectively, these results advance our understanding of the biological functions of monosaccharides and trace elements in sea urchins, highlighting their roles in stress adaptation under toxic element exposure. These establish a framework for investigating species-specific detoxification strategies and inform sustainable aquaculture practices to optimize resource utilization and support ecologically balanced industry development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32002414), Education Department of Liaoning Province of China (JYTMS20230475), and Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province of China (2025-MS-178). We thank Prof. Guodong Wang of Jimei University for collecting the sea urchin Anthocidaris crassispina from Jimei, Xiamen, China.

Authors’ Contribution

Methodology: HaoWen Li (Equal), Heng Wang (Lead). Formal Analysis: HaoWen Li (Equal), Fei Li (Equal). Investigation: HaoWen Li (Equal), Heng Wang (Equal). Writing – original draft: HaoWen Li (Lead), Heng Wang (Equal), Jun Ding (Equal). Writing – review & editing: HaoWen Li (Lead), Heng Wang (Equal), YaQing Chang (Equal). Conceptualization: Heng Wang (Equal), Jun Ding (Equal), YaQing Chang (Equal). Funding acquisition: Heng Wang (Lead). Supervision: Heng Wang (Lead), Jun Ding (Equal), YaQing Chang (Equal). Resources: Jun Ding (Equal), YaQing Chang (Equal).

Competing of Interest – COPE

No competing interests were disclosed.

Ethical Conduct Approval – IACUC

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Dalian Ocean University does not require authorization for the research on Strongylocentrotus intermedius and other echinoderms. During the farming and dissections, measures were taken to minimize animal suffering, such as providing water conditions that mimic the natural environment and performing rapid dissections.

Informed Consent Statement

All authors and institutions have confirmed this manuscript for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All are available upon reasonable request.

.png)

.png)

_and_gonad_(b)_of_four_sea_urchin_specie.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

_and_gonad_(b)_of_four_sea_urchin_specie.png)

.png)

.png)